Review by

Eric Hillis

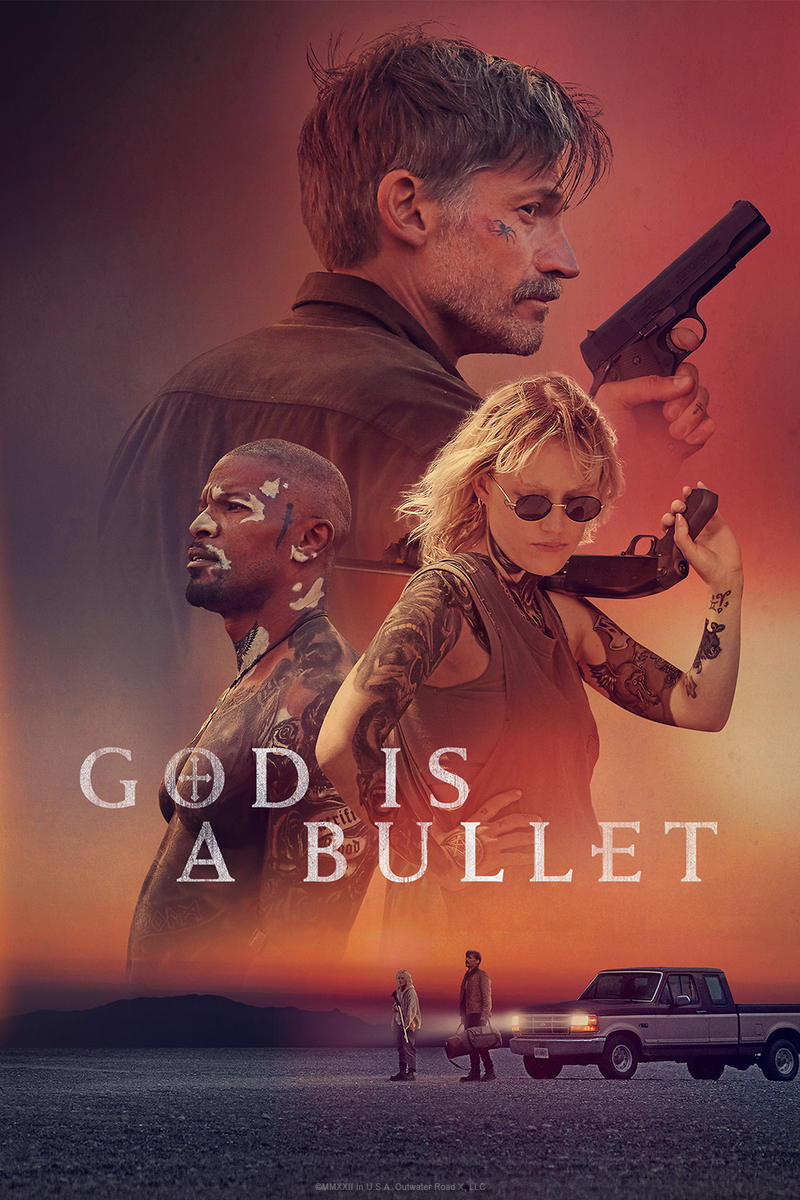

Directed by: Nick Cassavettes

Starring: Nikolaj Coster-Waldau, Maika Monroe, Jamie Foxx, Karl Glusman

God is a Bullet opens with the claim that it's "based on

a true story" and closes with a disclaimer informing the viewer that

what you've just watched actually bears no relation to anything that

occurred in real life. It's indicative of the schizophrenic quality of

writer/director Nick Cassavettes' adaptation of the 1999 book by

"Boston Teran," a pseudonym for what some believe to be a collective of

respected writers having some fun in the paperback world of genre

fiction. Cassavettes can't decide if he's making a gritty, existential

Paul Schrader thriller or a trashy Michael Winner romp. His film falls

flat on its face when it tries to imitate Schrader, whose 1979

Hardcore seems to be the main inspiration here, but is

more successful at replicating the over-the-top reactionary scuzziness

of Winner's films. Schrader is one of the best filmmakers of his

generation while Winner is a hack, so I guess it's no surprise that the

latter is the easier to imitate.

Nikolaj Coster-Waldau is miscast as mild-mannered, God-fearing

small town cop Bob Hightower. We're supposed to buy in to the Danish

hunk as a rural American rube because he's decked out in a Ned Flanders

mustache and square haircut. Bob's world is shattered when a

Manson-esque cult kills his ex-wife and kidnaps his teenage daughter.

With his police department proving inept at tracking down a bunch of

goons whose prominent face tattoos and impractical leather outfits would

make them stand out at a Mad Max cosplay convention, Bob decides to take

things into his own hands.

This sees Bob team up with Case (Maika Monroe), a spunky escapee

from a cult known as "The Left-Handed Path," which she believes is

responsible for the attack. It's the sort of pairing Schrader has fallen

back on several times - the repressed, conservative older man and the

libertine young woman – but in Cassavettes' hands it becomes a clunky

reworking of the classic It Happened One Night "Will they,

won't they?" dynamic as the two form an unlikely attraction.

With Bob forced by Case to get his body and face tattooed (by a

character played by Jamie Foxx and named "The Ferryman," in case

you didn't already get the metaphor) in order to fit in with her

underworld, there's a better version of this film in which Bob begins to

embrace this nihilistic world he's entered. It's the movie Schrader

would likely give us, but perhaps not what you should expect from the

director of The Notebook. It's briefly hinted at here when Bob sells out a female cult member,

leading to her demise, but it never reaches the levels of George C.

Scott in Schrader's Hardcore or his self-directed 1972

revenger Rage.

Bob has more in common with the sort of figures played by Charles

Bronson in the 1970s and '80s. Bronson was uniquely skilled at playing

men who seemed like your average uptight suburbanite until he took his

shirt off to reveal ridiculously toned abs. Coster-Waldau certainly has

the abs but never convinces as a "desk cowboy," as his Sheriff describes

him. This isn't helped by Bob's unconvincingly rapid transition into

John Rambo, stapling laughably gaping knife wounds in his stomach and

surviving a snake bite to the neck.

The over-the-top hero, the sassy young heroine and the

Hills Have Eyes villains would all work if the movie was

content to be the sort of exploitation fare such stereotypes suggest.

But Cassavettes has loftier ambitions, which results in eye-rolling

monologues about faith and some terrible use of rock music in montages

so badly synced with the chosen songs they become the cinematic

equivalent of listening to a DJ who can't beat match. Plenty of

filmmakers have managed to pull off the trick of combining arthouse with

grindhouse, including Cassavettes' own parents, but perhaps the trick is

to have an equal appreciation for both forms.