Review by

Benjamin Poole

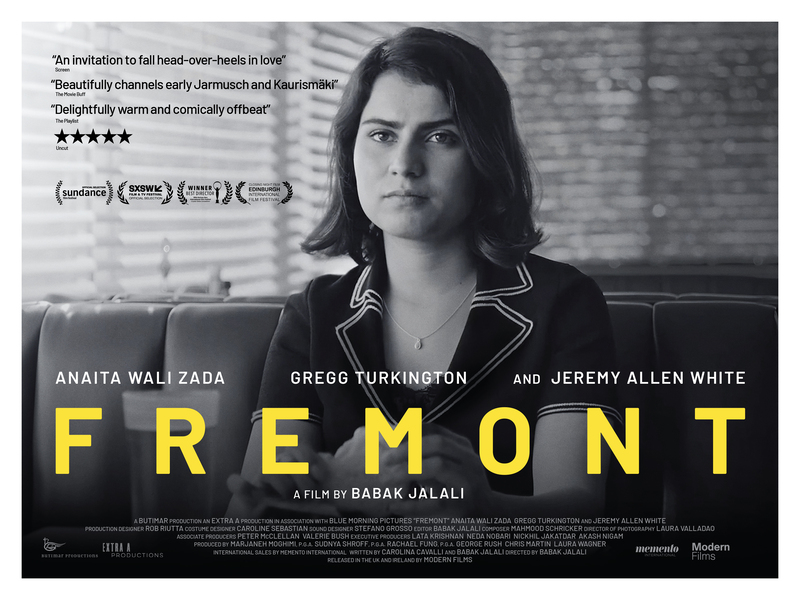

Directed by: Babak Jalali

Starring: Anaita Wali Zada, Gregg Turkington, Jeremy Allen White

The city doesn't care. Daily, nightly, a populace of millions shift

through its concrete arteries, swallowed up by the glass and steel

shadows its towering constructions throw. We go to the city to complete

a need, but the city only ever anonymises, incapable of acknowledging

our hopes and dreams (a side note; over the summer I rewatched the uber

text of this narrative type, Taxi Driver, and was struck by how congruous Travis - gormless, dangerous,

entitled - is with our modern incel culture: prophetic). In the case of

Babak Jalali's (writing with Carolina Cavalli) really

quite special Fremont, this dream is of an American flavour, with Afghan emigrant Donya (Anaita Wali Zada

- incredible) eking out a meagre existence while working in a factory in

Fremont. It is an ignominious profession following her previously more

vital role as an overseas translator for the U.S. army. Donya is

uncomplaining, yet haunted by her experiences of war, and, as an

immigrant in an anonymous city, alienated and deeply lonely.

Guided by Laura Valladao's monochrome photography,

Fremont's style communicates disaffection in shades of lush pewter and

silvers. We open in the fortune cookie factory where Donya works (the

history of the fortune cookie is an interesting little rabbit hole in

itself and supports Fremont's Americana themes). The heavy machinery, glum faces of the workers,

and rolling mass of produce is far removed from the whimsical magic

implied by a biscuit which can apparently divine fate. To compound the

point, we first see Donya on the fringes of a conversation with workers

about what one would do if they won a million dollars - the most

desolate of all workplace chats. Donya wanders the streets alone. She

visits a pro-bono therapist (I got the sense that he too, like everyone

else, is desperate for connection) for help with her insomnia but who,

wryly played by Gregg Turkington, is not much use at all: in one

of Fremont's most poignant jokes, a session concludes with Donya consoling him

through his tears.

An immigrant to America herself, Wali Zada is incredible in her first

role, and gives the disparate narrative and loose interactions of

Fremont human gravity. With her intense beauty, the camera

loves Wali Zada and, via her portrayal of stoic, relatable Donya, you

will too as she interacts with Fremont's gallery of quirky denizens. There is the friend who offers

knowing-but-pretty-shit-actually dating advice, the

well-meaning-but-patronising boss, his mean-spirited wife. Where do

people go in the city to find actual connections, to make friends, to

find love? When a co-worker drops dead on the job (another of

Fremont's sly, deadpan jokes) Donya is promoted to "fortune writer" for the

cookies, and decides to enclose a personal message along with her phone

number within the baked wafer folds of the confection...

The action has all the promise of a rom-com set up, but

Fremont has no such genre fealty, or interest in narrative

routine. In the initial sequences we are located within the frames of

Prime Indie: that is, the thick black and white mise-en-scene of

Jarmusch or Go Fish (love that film), along with the de

rigueur arch presentation of long-held static shots (an acid jazz score

follows Donya through the neon city streets, and we're back in 1994).

The deliberately nostalgic invocation is a bit like when an

oversaturated contemporary horror film trades off '80s memories, but

Fremont is more sincere than that, and utilises the retro

mode to consolidate its aura of displacement and artful isolation.

Among the picaresque is Donya's Afghan neighbour, who blanks her

throughout, deeming her a traitor in the same way that her home country

people do following her service with the American army.

Fremont presents the immigrant situation, and the empty

wish of the American dream, in ways which are subtle but persistent. We

see this most eloquently through a sweet analogy with White Fang,

Donya's therapist's favourite book and a canon text of American

actualisation: like the eponymous hybrid of the novel, Donya is viewed

with suspicion within her new context, and her supposed kinspeople also

deny her. This conclusive exposition is kept until the end of the second

act, up until which the film has gradually built its imperial sense of

solitude, strange claustrophobia and cultural incongruity in visual

waves of grey/gray.

Could romance come in the kind, teddy bear-like form of mechanic

Jeremy Allen White (a hunk who always looks on the verge

of tears?). If so, then the loneliness which wounds both characters is

assuaged by gentle and simple emotional honesty, forging a bond against

all the odds in the shadows of the city. Although its arty throwback

stylings may initially constern, the connection

Fremont ultimately makes with audiences will last long

after the credits.

Fremont is in UK/ROI cinemas from September 15th.