Review by

Eric Hillis

Directed by: Dmytro Sukholytkyy-Sobchuk

Starring: Oleksandr Yatsentyuk, Stanislav Potiak, Solomiya

Kyrylova, Ivan Sharan, Aleksandr Yarema, Olena Khokhlatkina, Rimma

Zyubina

Almost half of Ukraine is rural, a countryside constituted of remote areas

far from the developed towns and cities, wherein the sparse populace forge

a living from the land via traditional means and their rugged physicality.

Dmytro Sukholytkyy-Sobchuk's frankly astounding folk-thriller debut

Pamfir locates its action within the woody, earthy terrains

of such a milieu. It is a hard life in this border town on the edge of the

Carpathians. The weather is unrelenting in its murky coldness, yet the

hearts of the people beat warm.

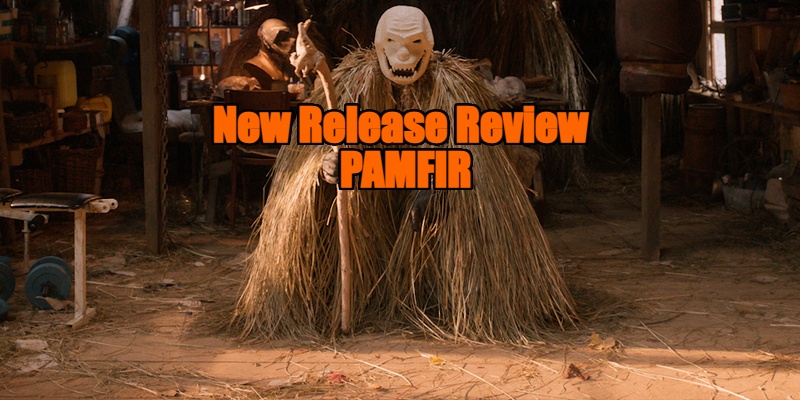

Pamfir (Oleksandr Yatsentyuk) is a brute, a man seemingly hewn from

the rocks and mountains which surround him. Returning to the village after

a spell working abroad, Pamfir (an epithet derived from Ukranian for

stone) is attempting to put his past as a smuggler - an inevitable

vocation within this deprived and dislocated mob-owned region - behind him

and go straight. After playfully tricking his pre-teen son Nazar (Stanislav Potiak) by hiding in a barn disguised as a monster, Pamfir is reunited with his

wife Olena (Solomiya Kyrylova). They fuck, hard and convincingly,

and once it's over, in a smooth motion Olena instinctively begins clipping

her husband's toenails: that's love. If Mr Tarantino is right in saying

that sex scenes are difficult to shoot, then Sukholytkyy-Sobchuk has

filmed a masterpiece in these few urgent moments, which communicate not

only the genuine love of this family, but also the hunger and imperative

need which characterise their lives.

The opening scenes of Pamfir have the portentous impact of

Heroic verse, yet the shifting subterfuge of the filmmaking hints at

darker developments to come. Winding up Nazar, Pamfir dresses in an

impressively constructed costume of flared straw and an outsize paper

mâché skull, fashioned in preparation for the Malanka festival. The

celebration is an abiding pre-Christian holdover which involves the men,

only the men, of the village dressing up as animals and gods (I think

Pamfir is going as Veles at the start: Ivan Mikhailov's excellent

production design inspired further investigation of this colourful

procession), in order to ward off any evil the forthcoming year may hold.

Some hope. Throughout the film, Mykyta Kuzmenko's camera is

furtive; restless, spying, showing us characters in reflection or obtuse

angles. We are complicit in the forces that will come to shape the fates

of Pamfir, Olena and Nazar despite their costumed rituals.

Pamfir exists within the demands of circumstance. He can only stay home

for the Malanka period before soon leaving town again to dig wells in

Poland. Nazar, dizzy with boyish adoration for his father yet limited by a

homely understanding of the world, designs to set fire to his dad's work

papers so the patriarch is forced to stay. Problem is that in doing so he

only goes and accidentally burns the town church down which is owned by

the local Odesa. This means that Pamfir is inexorably drawn in for one

last job, a thriller dynamic made fresh and original by the film's novel

context and the filmmaking's searing vigour. There is a ragbag crew,

dashes through snow laden forest filmed in fluid tracking shots, and

painful, affecting violence.

Yatsentyuk is superlative, his Pamfir a man struggling not so much against

the mob and the consequences of illegality, but his own dignity and need

to protect his family. That said, a standout scene features the man of

rock physically taking on a large gang of heavies and almost winning in a

swirling, unbroken medium shot of sheer genre excitement. A telling and

heart-breaking moment comes later wherein Olena admits that she has

"nothing": Pamfir at least has his masculine power, a strength which also

yet functions as a curse. The atavistic setting of

Pamfir enables Sukholytkyy-Sobchuk to examine masculinity

and all its lumbering responsibilities, an ineludible framework where

traditional gender roles are pervasively essential.

And with all that, there are moments of tenderness and keen humour... to

keep them sharp during their night-time border hopping, Pamfir and his

lads take a steroid which ultimately makes them priapic, leading to a

comedy montage of self-relief (men wanking is somehow always ridiculous

and funny). There are parallels to be drawn between the hand to mouth

existence of Pamfir's denizens and the tenacity of its grant funded, low budgeted

filmmakers, just as it is perhaps irresistible to conflate the micro of

Pamfir's beleaguered position with Ukraine's unstable macrocosm. Such

readings exist, but the pagan energy of Pamfir transcends

its conditional contexts and, in its final scenes especially, becomes a

universal treatise on what it means to be a man.

Pamfir is in UK/ROI cinemas from

May 5th.