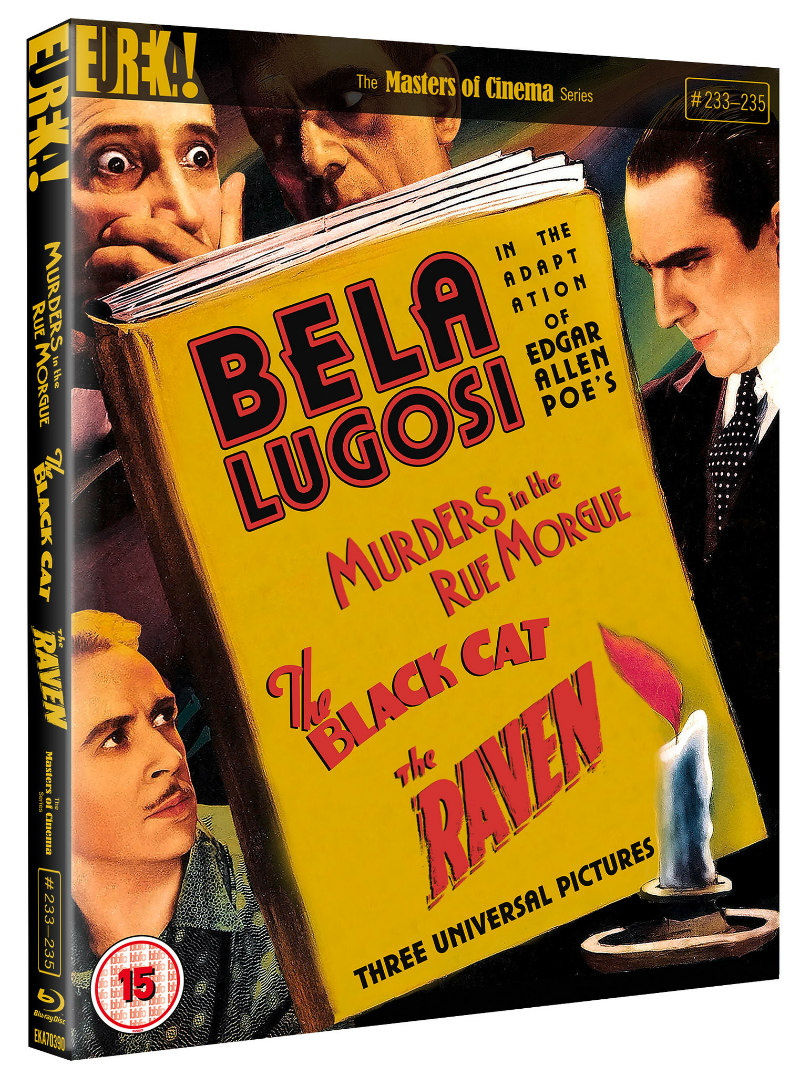

Boxset containing 1930s Poe adaptations Murders in the Rue Morgue, The Black Cat and The Raven.

Review by Eric Hillis

Following his success in the title role of Tod Browning's 1931 adaptation of Bram Stoker's Dracula, a role he had previously made his own on stage, Universal Pictures were eager to get Béla Lugosi into more horror movies. Oddly enough, while he introduced himself to the world as the suave and seductive Count Dracula, Lugosi would quickly find himself typecast in mad scientist parts.

He played variations of such a character in three films for Universal in the immediate years following Dracula. All loosely (and I mean LOOSELY) inspired by the work of Edgar Allan Poe, Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932), The Black Cat (1934) and The Raven (1935) may see Lugosi essaying demented doctors, but he brings something different to each role, unlike later movies where Lugosi's sinister scientists would become largely indistinguishable from one another.

Eureka Entertainment have gathered all three films for this handsome boxset. All three look stunning, presented in High Def 1080p, with The Raven presented from a 2K scan of the original film elements.

He played variations of such a character in three films for Universal in the immediate years following Dracula. All loosely (and I mean LOOSELY) inspired by the work of Edgar Allan Poe, Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932), The Black Cat (1934) and The Raven (1935) may see Lugosi essaying demented doctors, but he brings something different to each role, unlike later movies where Lugosi's sinister scientists would become largely indistinguishable from one another.

Eureka Entertainment have gathered all three films for this handsome boxset. All three look stunning, presented in High Def 1080p, with The Raven presented from a 2K scan of the original film elements.

Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932)

Directed by: Robert Florey

Starring: Béla Lugosi, Sidney Fox, Leon Ames, Bert Roach, Betty Ross Clarke, Charles Gemora

Lugosi and French director Robert Florey had been pencilled in for an adaptation of Mary Shelley's 'Frankenstein' before the studio handed that project over to British director James Whale, who awarded the title role to his compatriot Boris Karloff. As something of a consolation prize, Florey and Lugosi were instead gifted the first of what would become a cinematic trend of horror movies that served as Poe adaptations in name only.

The twist of Poe's original story, that of an ape being behind a series of murders in 19th century Paris, is put front and centre here. The ape in question, named Erik, is owned by Dr. Mirakle (Lugosi), who, when not showing off Erik to customers at a lurid sideshow, is engaged in experiments that involve him injecting the veins of abducted young woman with Erik's simian blood.

Mirakle sets his sights on society girl Camille (Sidney Fox) as his next victim, but the young lady's boyfriend, medical student and amateur sleuth Auguste Dupin (Leon Ames), is studying the corpses fished out of the Seine in the aftermath of Mirakle's failed experiments and is beginning to put two and two together.

Murders in the Rue Morgue is certainly a lesser entry in the Universal Horror cycle, but there's much of interest here for fans of such fare. Aided by ace cinematographer Karl Freund and set designer Herman Rosse, Florey draws heavily from German Expressionism. The Paris of Florey's picture is one of crooked angles and sinister shadows, Freund's deep focus lighting and the matte paintings of John P. Fulton combining to create the illusion that the city stretches far beyond the confines of the Universal backlot. A scene where Erik the ape's shadowy paw is seen entering Camille's bedroom is straight out of Murnau's Nosferatu. Elsewhere, Florey's camera is mounted in playfully expressive positions, like on a swing, making us dizzy along with Camille until Auguste grabs its rope and brings both his lover and the audience back to earth.

Murders in the Rue Morgue is notable also for an early role for Filipino performer Charles Gemora, who would come to be known as Hollywood's "King of the Ape-Men" for a series of movies that saw him donning a usually far from convincing gorilla costume (as the costume grew mangy, so too did the films). Florey makes the choice to only photograph the costumed Gemora in long shots, or those where he is partially concealed by shadow, opting for a real live baboon for close-ups. It may have proven effective in 1932, but the hi-def presentation here takes no prisoners, and Gemora's furry suit is all too visible.

Florey's film suffers from thin characterisation that never allows us to develop any real relationship with its bland hero and heroine. A couple of comic moments are overplayed, like Auguste's cheaply queer-coded housemate and a back and forth between Italian, German and Danish immigrants who each try to blame the others' nationalities on a murder. Stay on board and you'll be greeted with a thrilling climax in which Erik escapes across the Parisian rooftops with Camille under his hairy arm. Were the filmmakers of the following year's King Kong taking notes?

Lugosi and French director Robert Florey had been pencilled in for an adaptation of Mary Shelley's 'Frankenstein' before the studio handed that project over to British director James Whale, who awarded the title role to his compatriot Boris Karloff. As something of a consolation prize, Florey and Lugosi were instead gifted the first of what would become a cinematic trend of horror movies that served as Poe adaptations in name only.

The twist of Poe's original story, that of an ape being behind a series of murders in 19th century Paris, is put front and centre here. The ape in question, named Erik, is owned by Dr. Mirakle (Lugosi), who, when not showing off Erik to customers at a lurid sideshow, is engaged in experiments that involve him injecting the veins of abducted young woman with Erik's simian blood.

Mirakle sets his sights on society girl Camille (Sidney Fox) as his next victim, but the young lady's boyfriend, medical student and amateur sleuth Auguste Dupin (Leon Ames), is studying the corpses fished out of the Seine in the aftermath of Mirakle's failed experiments and is beginning to put two and two together.

Murders in the Rue Morgue is certainly a lesser entry in the Universal Horror cycle, but there's much of interest here for fans of such fare. Aided by ace cinematographer Karl Freund and set designer Herman Rosse, Florey draws heavily from German Expressionism. The Paris of Florey's picture is one of crooked angles and sinister shadows, Freund's deep focus lighting and the matte paintings of John P. Fulton combining to create the illusion that the city stretches far beyond the confines of the Universal backlot. A scene where Erik the ape's shadowy paw is seen entering Camille's bedroom is straight out of Murnau's Nosferatu. Elsewhere, Florey's camera is mounted in playfully expressive positions, like on a swing, making us dizzy along with Camille until Auguste grabs its rope and brings both his lover and the audience back to earth.

Murders in the Rue Morgue is notable also for an early role for Filipino performer Charles Gemora, who would come to be known as Hollywood's "King of the Ape-Men" for a series of movies that saw him donning a usually far from convincing gorilla costume (as the costume grew mangy, so too did the films). Florey makes the choice to only photograph the costumed Gemora in long shots, or those where he is partially concealed by shadow, opting for a real live baboon for close-ups. It may have proven effective in 1932, but the hi-def presentation here takes no prisoners, and Gemora's furry suit is all too visible.

Florey's film suffers from thin characterisation that never allows us to develop any real relationship with its bland hero and heroine. A couple of comic moments are overplayed, like Auguste's cheaply queer-coded housemate and a back and forth between Italian, German and Danish immigrants who each try to blame the others' nationalities on a murder. Stay on board and you'll be greeted with a thrilling climax in which Erik escapes across the Parisian rooftops with Camille under his hairy arm. Were the filmmakers of the following year's King Kong taking notes?

The Black Cat (1934)

Directed by: Edgar G. Ulmer

Starring: Béla Lugosi, Boris Karloff, David Manners, Julie Bishop, Egon Brecher

A spate of recent sci-fi thrillers - Ex Machina; Elizabeth Harvest; Exit Plan - have re-appropriated the trappings of Gothic horror from old dark houses to the shiny yet sterile interiors of modernist architecture. Director Edgar G. Ulmer got there first however. His in-name-only 1934 adaptation of Poe's The Black Cat takes place not in some damp old castle but within the clean white walls of a freshly built mansion, with barely a shadow in sight.

The elaborately designed home is that of "Austria's greatest architect" Hjalmar Poelzig (Boris Karloff, top billed as simply "Karloff"), who finds himself unexpectedly playing host to "Hungary's greatest psychiatrist" Vitus Werdegast (Béla Lugosi) and a pair of wet-behind-the-ears American newlyweds in mystery writer Peter Alison (David Manners) and his wife Joan (Julie Bishop, billed here under her previous moniker of Jacqueline Wells).

While the Alisons are simply seeking refuge following a car crash on the roads nearby, Werdergast have arrived with sinister intentions. During the war, he and Poelzig served together. Amid a bloody battle, Poelzig fled, leaving Werdergast to be captured by the enemy and sentenced to 15 years in prison. Werdergast believes Poelzig is guilty of stealing his wife and daughter. Poelzig introduces Werdergast to his secret basement, where he keeps a collection of female corpses frozen in suspended animation, including Werdergast's wife. He doesn't reveal his other secret, that he has made Werdergast's daughter his bride.

What ensues is a battle of wits between Poelzig and Werdergast, as the former sets his sights on making Joan his latest victim during a Satanic ritual planned for the following night, while the latter sets in motion plans to take his revenge on the architect.

Ulmer seems purposely out to subvert expectations here. Despite his sinister entrance, riffing on his Dracula schtick, Lugosi is soon revealed to be the closest the film has to a hero, rather than Manners' Peter, who proves ineffectual when all hell threatens to break loose. The black and white colour scheme is turned on its traditional head, with our heroes escaping from Karloff's dazzling white interiors into the comparative safety of the shadowy darkness of night. It's one of the first movies to suggest the now clichéd idea that members of elite society may be involved in secret Satanic gatherings, and along with Karloff's gruesome denouement, in this way it feels like the primary influence on Pascal Laugier's 2008 New French Extremity cornerstone Martyrs, which makes all that's implicit in Ulmer's film wildly explicit.

As with Murders in the Rue Morgue, The Black Cat suffers from a lack of protagonists whose fates we sufficiently care about. Joan is barely a character, spending most of the movie asleep, so it's difficult to get invested in her predicament, while Peter is one of those bland types who seems to have traded personality for height. Next to the old world charm and malice of Karloff and Lugosi, they eventually crumble like wet cardboard. As a story of innocents happening upon a madman's lair, it's a poor cousin of its contemporaries like 1932's The Most Dangerous Game and Island of Lost Souls, but The Black Cat holds much in the way of historical value for horror fans, who will appreciate the ways in which Ulmer cleverly plays with the conventions of the genre.

A spate of recent sci-fi thrillers - Ex Machina; Elizabeth Harvest; Exit Plan - have re-appropriated the trappings of Gothic horror from old dark houses to the shiny yet sterile interiors of modernist architecture. Director Edgar G. Ulmer got there first however. His in-name-only 1934 adaptation of Poe's The Black Cat takes place not in some damp old castle but within the clean white walls of a freshly built mansion, with barely a shadow in sight.

The elaborately designed home is that of "Austria's greatest architect" Hjalmar Poelzig (Boris Karloff, top billed as simply "Karloff"), who finds himself unexpectedly playing host to "Hungary's greatest psychiatrist" Vitus Werdegast (Béla Lugosi) and a pair of wet-behind-the-ears American newlyweds in mystery writer Peter Alison (David Manners) and his wife Joan (Julie Bishop, billed here under her previous moniker of Jacqueline Wells).

While the Alisons are simply seeking refuge following a car crash on the roads nearby, Werdergast have arrived with sinister intentions. During the war, he and Poelzig served together. Amid a bloody battle, Poelzig fled, leaving Werdergast to be captured by the enemy and sentenced to 15 years in prison. Werdergast believes Poelzig is guilty of stealing his wife and daughter. Poelzig introduces Werdergast to his secret basement, where he keeps a collection of female corpses frozen in suspended animation, including Werdergast's wife. He doesn't reveal his other secret, that he has made Werdergast's daughter his bride.

What ensues is a battle of wits between Poelzig and Werdergast, as the former sets his sights on making Joan his latest victim during a Satanic ritual planned for the following night, while the latter sets in motion plans to take his revenge on the architect.

Ulmer seems purposely out to subvert expectations here. Despite his sinister entrance, riffing on his Dracula schtick, Lugosi is soon revealed to be the closest the film has to a hero, rather than Manners' Peter, who proves ineffectual when all hell threatens to break loose. The black and white colour scheme is turned on its traditional head, with our heroes escaping from Karloff's dazzling white interiors into the comparative safety of the shadowy darkness of night. It's one of the first movies to suggest the now clichéd idea that members of elite society may be involved in secret Satanic gatherings, and along with Karloff's gruesome denouement, in this way it feels like the primary influence on Pascal Laugier's 2008 New French Extremity cornerstone Martyrs, which makes all that's implicit in Ulmer's film wildly explicit.

As with Murders in the Rue Morgue, The Black Cat suffers from a lack of protagonists whose fates we sufficiently care about. Joan is barely a character, spending most of the movie asleep, so it's difficult to get invested in her predicament, while Peter is one of those bland types who seems to have traded personality for height. Next to the old world charm and malice of Karloff and Lugosi, they eventually crumble like wet cardboard. As a story of innocents happening upon a madman's lair, it's a poor cousin of its contemporaries like 1932's The Most Dangerous Game and Island of Lost Souls, but The Black Cat holds much in the way of historical value for horror fans, who will appreciate the ways in which Ulmer cleverly plays with the conventions of the genre.

The Raven (1935)

Directed by: Lew Landers

Starring: Béla Lugosi, Boris Karloff, Lester Matthews, Irene Ware, Samuel S. Hinds

One of the first movies to address toxic fan culture was this deliriously fun horror from director Lew Landers (credited here as Louis Friedlander). Béla Lugosi plays Edgar Allan Poe obsessed retired surgeon Richard Vollin, who like Peter Cushing in 'The Man Who Collected Poe' segment of 1967 horror anthology Torture Garden, has a collection of Poe ephemera which extends to the working torture devices in his basement.

Vollin is lured out of retirement by Judge Thatcher (Samuel S. Hinds), whose ballerina daughter Jean (Irene Ware) has been left facially scarred by a car accident. When Vollin restores Jean's face to its previous beauty, the young woman develops a crush on her saviour, leading the ungrateful Judge to warn Vollin off making any advances toward his daughter. Rightly outraged, Vollin invites the extended Thatcher family to an evening at his home, where he plans to make Jean his equivalent of Poe's doomed literary love Lenore.

Boris Karloff is top-billed in this one, playing Edmond Bateman, a fugitive murderer who much like Humphrey Bogart in 1947's Dark Passage, asks Vollin to carve him a new face. Vollin does just that, but the fresh fizzog he gives Bateman is horrifically disfigured. The mad surgeon makes Bateman his man-servant and partner in crime, promising to restore his face once he has helped him play out his fiendish games with the Thatchers.

The Raven adopts a format that would prove popular among low budget horror movies and mysteries of the '30s, that of assembling a group of characters in a mansion where someone or something (often a man in a gorilla costume) threatens their lives. Such movies are more often than not, a lot of fun, and Landers' film is one of the most enjoyable examples of its type.

Lugosi is visibly having a ball here, chewing up the scenery before said scenery takes its revenge in the gruesome climax. Watching him taunt Karloff's tortured Bateman with such malevolent glee, you can't help but wonder if Lugosi was channelling his own resentment at how Universal insisted on giving the Englishman top-billing despite this clearly being Lugosi's movie.

While the film bears no resemblance to Poe's famous poem, it does at least incorporate Poe's work to some degree. The movie opens with Lugosi reciting the famous verse in his unmistakeable drawl, while later Jean performs a ballet based on Poe's Lenore. It offers some striking originality, particularly in the details of Lugosi's home, rigged up up with bedrooms that can be brought down to the basement by pulling a lever, and a closing wall room that likely influenced George Lucas.

It's hard to believe now, but the relatively innocent thrills of The Raven caused quite the stir in 1935. The film was banned in multiple countries, and in the UK it led to the introduction of the "H for Horrific" certificate, which along with the introduction of the Hays code, effectively killed off the production of horror movies in mainstream Hollywood for the remainder of the decade.

One of the first movies to address toxic fan culture was this deliriously fun horror from director Lew Landers (credited here as Louis Friedlander). Béla Lugosi plays Edgar Allan Poe obsessed retired surgeon Richard Vollin, who like Peter Cushing in 'The Man Who Collected Poe' segment of 1967 horror anthology Torture Garden, has a collection of Poe ephemera which extends to the working torture devices in his basement.

Vollin is lured out of retirement by Judge Thatcher (Samuel S. Hinds), whose ballerina daughter Jean (Irene Ware) has been left facially scarred by a car accident. When Vollin restores Jean's face to its previous beauty, the young woman develops a crush on her saviour, leading the ungrateful Judge to warn Vollin off making any advances toward his daughter. Rightly outraged, Vollin invites the extended Thatcher family to an evening at his home, where he plans to make Jean his equivalent of Poe's doomed literary love Lenore.

Boris Karloff is top-billed in this one, playing Edmond Bateman, a fugitive murderer who much like Humphrey Bogart in 1947's Dark Passage, asks Vollin to carve him a new face. Vollin does just that, but the fresh fizzog he gives Bateman is horrifically disfigured. The mad surgeon makes Bateman his man-servant and partner in crime, promising to restore his face once he has helped him play out his fiendish games with the Thatchers.

The Raven adopts a format that would prove popular among low budget horror movies and mysteries of the '30s, that of assembling a group of characters in a mansion where someone or something (often a man in a gorilla costume) threatens their lives. Such movies are more often than not, a lot of fun, and Landers' film is one of the most enjoyable examples of its type.

Lugosi is visibly having a ball here, chewing up the scenery before said scenery takes its revenge in the gruesome climax. Watching him taunt Karloff's tortured Bateman with such malevolent glee, you can't help but wonder if Lugosi was channelling his own resentment at how Universal insisted on giving the Englishman top-billing despite this clearly being Lugosi's movie.

While the film bears no resemblance to Poe's famous poem, it does at least incorporate Poe's work to some degree. The movie opens with Lugosi reciting the famous verse in his unmistakeable drawl, while later Jean performs a ballet based on Poe's Lenore. It offers some striking originality, particularly in the details of Lugosi's home, rigged up up with bedrooms that can be brought down to the basement by pulling a lever, and a closing wall room that likely influenced George Lucas.

It's hard to believe now, but the relatively innocent thrills of The Raven caused quite the stir in 1935. The film was banned in multiple countries, and in the UK it led to the introduction of the "H for Horrific" certificate, which along with the introduction of the Hays code, effectively killed off the production of horror movies in mainstream Hollywood for the remainder of the decade.

Extras:

Feature commentaries by Gregory William Mank on Murders in the Rue Morgue and The Black Cat; feature commentaries on The Raven by Gary D. Rhodes and Sam Deighan; a video essay on cats in horror by writer and film historian Lee Gambin; a video essay on American Gothic by critic Kat Ellinger; 'The Black Cat' episode of radio series Mystery In The Air, starring Peter Lorre; 'The Tell-Tale Heart' episode of radio series Inner Sanctum Mysteries, starring Boris Karloff; 'The Tell-Tale Heart' read by Béla Lugosi; vintage footage; new interview with critic/author Kim Newman; a collector’s booklet featuring new writing by film critic and writer Jon Towlson, a new essay by film critic and writer Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, and rare archival imagery and ephemera.

Three Edgar Allan Poe Adaptations Starring Béla Lugosi is on limited edition blu-ray July 20th from Eureka Entertainment.

"Takes a simple and interesting premise, and bogs it down in tepid drama and groan inducing clichés."— The Movie Waffler (@themoviewaffler) July 14, 2020

In the latest instalment of his Strange Cinema Cavalcade, @strangecinema65 looks at INHERITANCEhttps://t.co/Bp4CvPtFwh pic.twitter.com/Jj7f4zFK1i