Words by

Ren Zelen

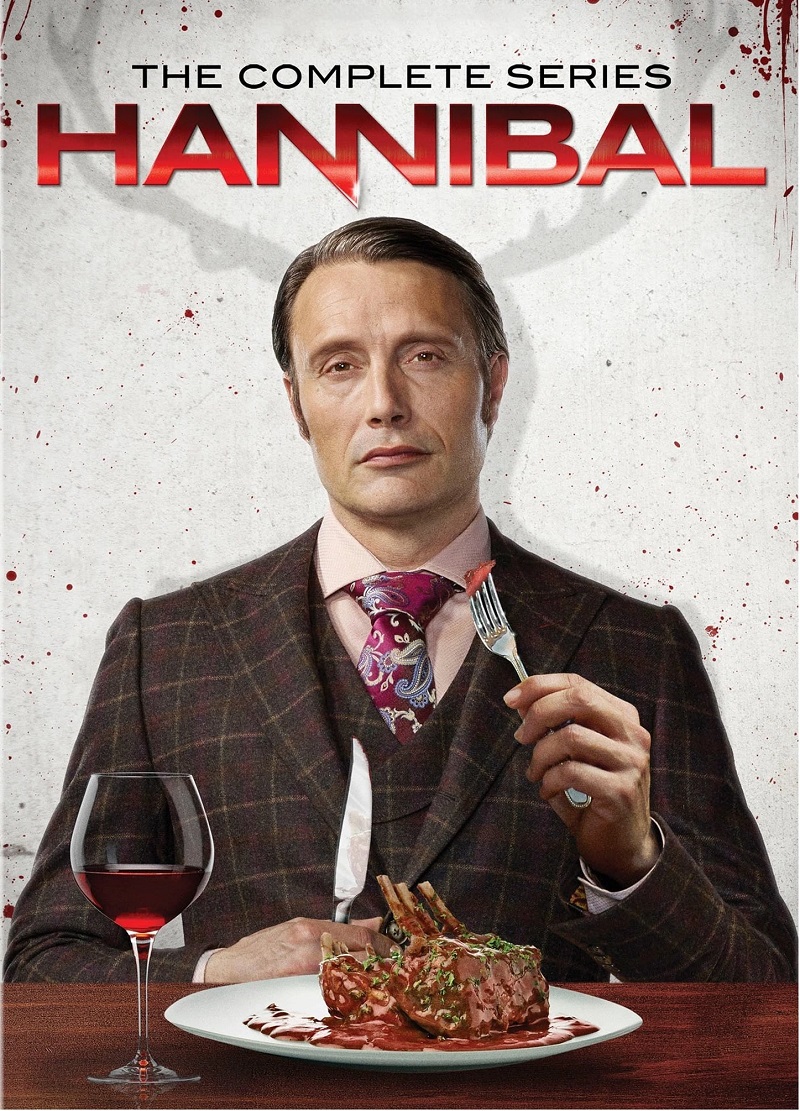

As production on Bryan Fuller's newest film,

Dust Bunny, begins in Budapest and reunites the director with

Mads Mikkelsen, his "Hannibal Lecter," it might seem a good time to

rewatch and reappraise Fuller's aesthetically lush, psychologically rich,

Hannibal adaptation, now that all three series are airing on Netflix.

Acclaimed by critics, including "Roger Ebert," who declared that Fuller's

Hannibal was the "Best Drama on Television," the show

nevertheless failed to gather as wide an audience as it deserved. Possibly

this was due to the success of the films previously made about

Thomas Harris's most notorious character.

However, to anyone who has watched Fuller's adaptation, there is no doubt

that the Hannibal Lecter created by Mikkelsen is a standout performance.

Anthony Hopkins' Lecter may have shown us a monster, but Mikkelsen is

Satan himself.

Having the luxury of 36 hours of film, Fuller and Mikkelsen created a

complex, compelling, and enthralling Hannibal Lecter - attractive and

repugnant in unsettlingly equal measures.

Certainly, the show is violent, and this may have been a factor in making

it one to be avoided by more sensitive TV viewers (I took some persuading

myself) but with Fuller's heightened aesthetic, murder becomes a Grand

Guignol performance, elevated to the level of high Art. It never sinks to

the level of gore for gore's sake but is a staged and highly stylised

outward expression of a character's inner turmoil, trauma or madness.

There is an emotional and psychological intensity beneath the carnage that

other horror offerings generally fail to provide.

Mikkelsen's Hannibal is a respected psychiatrist in Baltimore but is also

a serial killer who has perfected the image of a mild, scrupulously

well-mannered sophisticate. Mikkelsen plays him with a psychopathological

insouciance. He is a man who can weep at the opera and who always knows

the right thing to say, whose dialogue has the wisdom of poetry, but those

stylish suits hide the soul of a killer.

Will Graham, as played by Hugh Dancy, is a hyper-sensitive criminal

profiler tasked by the FBI to help them hunt murderers who display

extraordinary modi operandi. Despite being too "unstable" to work as an

official agent, Graham is successful in his ability to help to catch

killers because of his unique gift of empathy. It is a gift which is also

a curse and is the source of his "instability," as the act of identifying

with the most damaged and violent killers has a traumatising effect on

Graham's vulnerable psyche.

Under advisement from Graham's colleague and closest friend Dr. Alana

Bloom (Caroline Dhavernas), Dr. Lecter is recruited by FBI overseer

Jack Crawford (Laurence Fishburne) to monitor Graham's mental

health while he tackles his distressing job. This brings Graham, Crawford,

Bloom et al into Lecter's orbit, as they strive to track down serial

killers - the Minnesota Shrike, his "copycat," and the Chesapeake Ripper,

amongst other killers.

Suspense comes from the bizarre episodic murders Graham is tasked with

solving, but primarily from the mind games that ensue. This is where

Mikkelsen's Hannibal comes into his own. Hannibal is surrounded by

exceptionally intelligent people, but he is always the smartest person in

the room, always five chess moves in front of everyone else - those around

him are chess pieces he moves around a board of his making. This is his

design.

To his collegues, his patients, his acquaintances, he is urbane and

sophisticated – a compassionate psychiatrist and a well-known gourmand,

always ready to offer help, impressing his guests with his erudite

conversation, his exquisite taste and his lavish, epicurean dinner

parties.

As Lecter observes Graham, he becomes fascinated by Will's particular gift

of empathy. What is at first interest in an unusual patient soon becomes

an intellectual challenge – can Hannibal use Will's extreme empathy to

break him down psychologically and mould a decent man into a killer, or

into an acolyte? Or, if Will proves to be resilient, how can Hannibal

prevent the man who is most likely to guess his secret from exposing him?

The way in which Hannibal deftly manipulates those around him is uniquely

compelling, and highly frustrating, as the viewer knows what none of the

characters can perceive, despite their intelligence. The only one who may

have insight is Gillian Anderson's character, psychiatrist Bedelia

Du Maurier, herself ensnared in Hannibal's net. Anderson gives an

impressive performance, walking the line between a cool, measured, assured

woman, who also happens to be terrified.

It becomes distressing to see Graham reduced to a feverish victim on the

verge of mental breakdown by the therapist masquerading as his concerned

friend. It's a further shock when we realise, that should events begin to

get uncomfortable for Hannibal, he has been meticulously laying down a

"Plan B" (and even a "Plan C") all along.

Although the drama centres on the cat-and mouse balance of the

relationship between Hannibal and Graham, the subordinate characters are

given scope to be individually interesting in themselves. Always playful,

Fuller has rearranged races and genders – FBI boss Jack Crawford (a

commanding Fishburne) becomes African-American, sympathetic crime-scene

investigator Beverly Katz (Hettienne Park) is Asian-American,

Will's confidant, Dr Alan Bloom becomes Dhavernas's gently feminine Alana

and Lara Jean Chorostecki plays Freddie Lounds as an unscrupulous,

inveigling female hack. This diversity makes the interplay between the

characters more complex and intriguing than those in Harris's simple

white, male-dominated world.

The season finale might be seen as a bloodbath which aims to shock but

does so partly because the show is until then, so controlled, restrained

and unapologetically artistic. Violence for Mikkelsen's Hannibal is a

means to an intellectual or aesthetic goal – an exercise of power over

events around him, but this god-like position demands a distance from the

people he could metaphorically (and literally) consume. Hence his desire

to connect with and control Graham, his polar opposite and psychological

adversary, which begins to take on the frisson of the homoerotic.

For viewers who are familiar with Fuller's previous work; the highly

original Pushing Daisies, the comedic fantasy of Wonderfalls, the macabre kookiness of Dead Like Me - there are a few

"self-references" hidden in Hannibal that will amuse them

and some familiar faces from these previous series. Also present is the

jet-black humour which he gleefully interjects into the darkest of

material.

What we are invited to consume is a contrast of flavours - the sweet and

the sour, the bitter and the bland - it might not be to everyone's taste,

but all together Hannibal makes a veritable feast for the

mind and the senses.