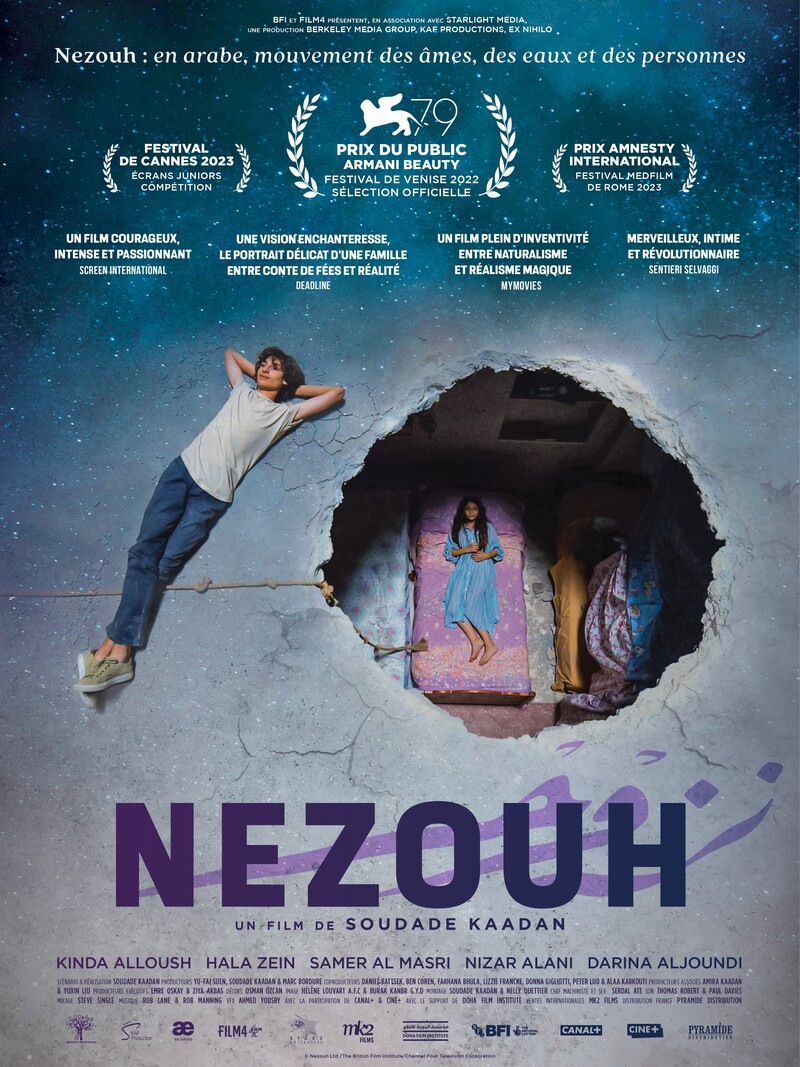

A family in Damascus is divided over whether to stay in their home or

face an uncertain life as refugees.

Review by

Benjamin Poole

Directed by: Soudade Kaadan

Starring: Samer Al Masri, Kinda Alloush, Hala Zein, Nizar Alani

The conflict which affects the Middle Eastern family unit of

Soudade Kaadan's Nezouh is never truly specified: the

narrative is located within Damascus, but indexical features such as

technology and clothes could be from 10 years ago or yesterday, such is

the meagre bricolage of what Zeina (Hala Zein), Hala (Samer al Masri) and Mutaz (Samir Almasri) have scrambled together in war torn

Syria, a doomed milieu where even fresh water is precious.

We open with a

tight shot of tween Zeina hidden beneath furniture, etching an

illustration into the torch lit wood, establishing Nezouh's expressive use of space. A transition takes us to the source of

violent noise - not, as we may fear, the sound of warfare, but a recently

repaired combustion engine which paterfamilias Mutaz has been working on

in the front room of the family's small, storied flat. Mum Hala is in the

background, thinking, tense... The scene exemplifies the family dynamic of

Nezouh: Mutaz is a cheerful optimist, who wants to provide for his family, yet

is restricted by his context; Zeina is a child with a fanciful imagination

while Hala is careful and cautious.

Fairly soon there is another massive loud noise in the flat: this time an

actual bomb which blows the windows of the apartment, leaves a perfect

metre wide hole above Zeina's bed, and leaves the living space looking

like, well, like a bomb has hit it. The family, however, are mercifully

unharmed. Views from the recently perforated homestead reveal a concrete

conurbation of similarly jagged buildings and ruined homes (the location

photography is poignant because it reminds the viewer that this situation

was/is a reality). I mean, where would you go if a bomb blasted a hole in

your ceiling? Neighbours, friends? If they're in the city, chances are

that they're in similarly precarious straits, as illustrated by the

cluster of residents from the opposite high rise, also bombed yet shouting

cheerful support. As a character says, "laughter is the best medicine..."

The surreality of how cheerfully people respond to acts of war, of how

quotidian the destruction and terror is within Nezouh, is compounded by the film's magic realism bent which comes courtesy of

Zeina, who daydreams that the hole in her ceiling is a portal to another

world. In evocative and poetic scenes, the blue sky becomes the infinite

ocean with the night stars skimming stones. One day, a pretty

neighbourhood boy pokes his head through the hole, too. Amer (Nizar Alani) is an amateur filmmaker, and, in the course of their budding

friendship, shows Zeina footage of the oceans she so dreams of (for a

while, there is a reading that suggests Amer may be an imaginary friend,

too, such is his beatific nature). The conceit is clear and subtly

chilling. The only escape that innocent Zeina enjoys is through her

imagination, but creative thoughts are no barrier against falling bombs or

the encroaching army...

As this is going on, seen in glimpses is the growing conflict between

Mutaz and Hala. She wants to leave and take Zeina, while Mutaz is

determined to stick around. The situation is precarious: if they stay,

then they, and, it is suggested, especially the women, risk the wrath of

the marauding army. But if they go, then they are in the wild, with no

shelter. As Mutaz argues, they would be living in "streets, car parks,

camps," and there is the unresolved matter of Zeina's older sister who

escaped but has since seemingly disappeared with no contact... Kaadan

draws her characters with a careful, even hand, sympathising with the

sense of pride which Mutaz clings to, and his shame of not living up to

it.

Nezouh's dichotomy of inside/outside is literalised in the film's final act,

where certain characters do leave the apartment, canvassing the wide

ranges of the city and the treacherous surrounding spaces. With their

picaresque air, perhaps some of the film's tightly wound power is

diminished in these final scenes, but by then we're deeply invested in the

narrative with its charming and immensely likeable characters. If there is

a happy ending, then it is welcome: a surprising twist which is as

transient and rarefied as one of Zeina's daydreams.

Nezouh is on UK/ROI VOD now.