Review by

Eric Hillis

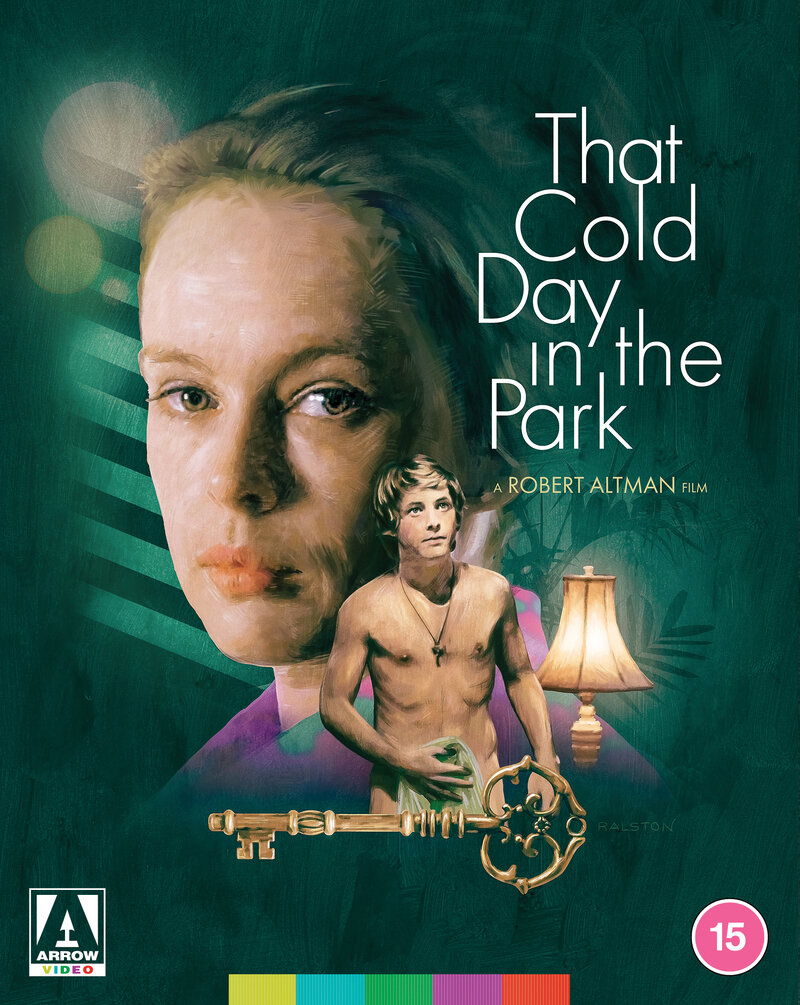

Directed by: Robert Altman

Starring: Sandy Dennis, Michael Burns, Susanne Benton, Luana Anders, John Garfield Jr., Michael Murphy

"I'm young at heart!" "50 is the new 30!" "You're only as young as you

feel!" We can delude ourselves as much as we want regarding the aging

process but the harsh truth is that even if you're in the improbably good

shape of a Tom Cruise or Jennifer Lopez, and even if you're the envy of your

peers, you're not fooling the young. To the young, anyone over 30 is over

the hill. You might pride yourself on being a 40-year-old with the physique

of a competitive swimmer, but all young people will see are wrinkles and

sagging flesh. Well at least those of us who no longer have our youth can

console ourselves with the fact that we're currently living in an age when

it sucks to be young, when young people are forced to live indefinitely with

their parents thanks to the western world's housing crisis and inaffordable

rents. Maybe being an old fart isn't so bad.

Imagine how awful it must have been to be an old fart in the 1960s though,

a time when it was great to be young. You've got to feel for all those poor

bastards who spent their 17th birthday storming a beach in France under a

hail of bullets, only to see their sons celebrate their 17th birthday at a

rave-up surrounded by mini-skirted dollybirds, tuning in and dropping out to

the groovy hit sounds of beat combos. The late '60s saw a wave of (mostly

British) psycho-thrillers in which the villains were often above a certain

age while their victims were youngsters. You have to wonder if the

filmmakers weren't exorcising their resentment at having missed out on this

glorious time to be young. It's telling that we didn't get similar movies

from the US at this time, as being a young man in 1960s America was

tantamount to a death sentence thanks to the Vietnam draft. I imagine a lot

of young American men wished they were 40 in the '60s. The youth of America

were to be pitied rather than envied, unlike the young hepcats of swinging

sixties Britain.

Robert Altman's 1969 film That Cold Day in the Park is

the closest the US got to emulating those mean-spirited British thrillers of

the era, though it's shot and set in Vancouver. That Canadian city's

constant rain, general bleakness and ex-pat community might even fool a

viewer into believing they're watching a British film. Altman's film

(scripted by British writer Gillian Freeman from a book by

Richard Miles) deals with a very British preoccupation, that of

repression, as embodied by Sandy Dennis's spinster Frances. We're

never told Frances's age but Dennis was a mere 31 at time of filming. But in

1969 being 31 probably felt like being 60 today. Frances lives a drab life

and it's clear the swinging '60s passed her by (if it even happened in

Canada). She's surrounded by old people, as though she inherited the family

of a dead spouse. An aging doctor (Edward Greenhalgh) fancies taking

her as a wife, but Frances finds him repulsive.

While hosting a dinner party for her circle of old fogeys, Frances become

enamoured with a teenage boy (Michael Burns) she sees sitting on a

bench in the rain in the park opposite her apartment. When the guests leave

she invites the boy (who remains nameless throughout) into her home, runs

him a bath and offers him food. The boy refuses to speak but engages in a

slapstick dance. With his mop of blond curls, the boy resembles a sinister

Harpo Marx with his mute antics. The silence is filled by Frances talking

incessantly in a nervous manner. After tucking the boy into a spare bed,

Frances locks the door, but the boy departs through the window and visits

his hippy sister Nina (Susanne Benton) and her draft-dodging American

boyfriend Nick (John Garfield Jr.) on their houseboat. Turns out the

boy isn't mute at all, it's simply an act, one which Nina claims he's been

pulling off since childhood. Rather than steering clear of the obviously

deranged Frances, the boy returns, but his motives for doing so are

unclear.

Frances' motives for keeping the boy in her home are all too clear however.

It's obvious she sees him as a cure for her sexual frustration, even

visiting a family planning clinic to have a diaphragm fitted in preparation

for some grand seduction. But just as she's repulsed by her doctor suitor's

advanced age, the boy has no interest in hooking up with a woman in her

thirties.

Critics at the time of That Cold Day in the Park were

unreceptive to its cynicism, likely because it was so fresh they simply

didn't know what to make of it. We've now become accustomed to films by the

likes of Lars von Trier and Michael Haneke featuring psychologically

troubled women being put through the ringer (some would say tortured by the

filmmakers), but in 1969 there simply weren't many characters like Frances

on screen. It wasn't Altman's first film but it's the first recognisably

Altman film, establishing some of his trademarks. When Altman's camera

drifts away from his leading lady to eavesdrop on conversations held by

background figures, 1969 audiences were likely stumped as to why a filmmaker

would do such a thing. They may have surmised that Altman was highlighting

the lives being lived on the lonely Frances' periphery, but now we know it's

simply what Altman does. Altman's ability to quickly establish a dynamic

with an economic setup is on display here, particularly in an impressive

scene when the boy returns to his family home and the camera remains outside

the house. We can't hear what's being spoken inside but what we observe

through the windows tells us that the boy puts on a very different front for

his parents than in while in the company of Frances and Nina.

With Altman now associated primarily with his ensemble dramas (to the

degree that the Independent Spirit Award for Best Ensemble is named in the

director's honour), it's easy to forget how many great individual lead

performances his early films featured. Dennis was never better than she is

here. She makes her Frances both terrifying and sympathetic, perhaps the

closest a female performer has come to replicating Anthony Perkins' career

defining turn as Norman Bates. There's not much to like about Frances and

yet we feel a crushing sympathy for the character, and the more pathetic she

acts the more difficult it becomes to watch her descent into madness.

If you have any anxiety regarding growing old,

That Cold Day in the Park will prove a deeply uncomfortable

experience. Through the words and actions of both the boy and Frances, we're

constantly reminded of how negatively we're viewed by those younger than us.

In an early attempt to impress the boy, Frances puts on a record she

believes he'll enjoy, but behind her back he rolls his eyes at how out of

touch she is with his generation's tastes. Later Frances delivers a

monologue about how unattractive she finds the doctor, describing in detail

how his old man smell turns her off. It's absolutely brutal. In his

contemporary review, Roger Ebert panned the film for not being a

conventional horror movie (was any mainstream critic so wrong so often?

*cough* Mark Kermode *cough*), but if you're over 30

That Cold Day in the Park is as disturbing and unsettling as

any explicit piece of body horror. It's as occupied with the limits of the

flesh as anything by Cronenberg or Barker.