Review by

Eric Hillis

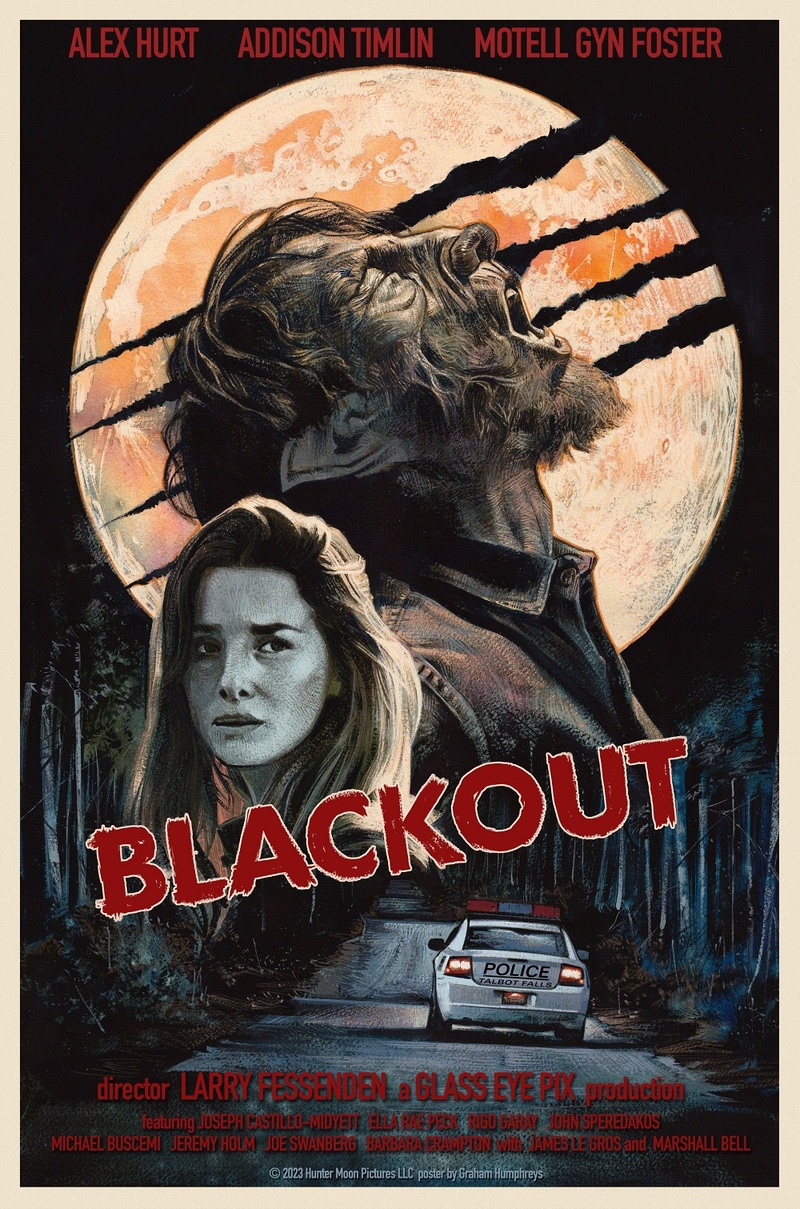

Directed by: Larry Fessenden

Starring: Alex Hurt, Addison Timlin, Motell Gyn Foster,

Marshall Bell, Barbara Crampton, Kevin Corrigan, James Le Gros

Since long before the irksome term "elevated horror" was first coined,

writer/director Larry Fessenden has been making the sort of movies

that would likely be lumped under that label if released today. He's

previously taken fictional monsters like vampires (Habit) and Frankenstein (Depraved), along with a mythical creature from Native American lore (Wendigo) and applied a gritty and grounded approach far from traditional Hollywood

conventions. With Blackout however he maintains his

distinctive lo-fi style while also paying tribute to classic horror, in

particular Universal's 1941 production of The Wolf Man.

That movie famously starred Lon Chaney Jr. as Larry Talbot. Here, the

fictional setting is a small American town named Talbot Falls. In

The Wolf Man, Chaney's Talbot had an estranged relationship with his father, the lord

of a small Welsh village, which was ultimately reconciled. Charley (Alex Hurt, who looks like a cross between Tom Cruise and Dustin Hoffman but is

actually the son of the late William Hurt), the protagonist of

Blackout, has similarly lived in his father's shadow, but there can be no

reconciliation as his old man (portrayed in photos by William Hurt) recently

passed away. Charley's life is a mess. He lives in a motel room, has lost

his painting job after being fired by local corrupt landowner Hammond (Marshall Bell), and has ended his relationship with Hammond's daughter Sharon (Addison Timlin). He's also dogged by alcoholism.

Those are the least of Charley's issues however. On top of everything else,

whenever there's a full moon he sprouts fangs and turns into a werewolf.

Having already claimed the lives of a couple of lovers enjoying a late night

outdoors shagging session, Charley decides it's best for everyone if he offs

himself. With the aid of a friend, Earl (Motell Gyn Foster), he has

concocted a plan to have his transformation captured on video before Earl

shoots him with a gun loaded with custom made silver bullets. Before his act

of assisted suicide he has a few things to clear up. Going through some of

his father's old documents, he's found what he believes is evidence of

corruption concerning Hammond's real estate plans, which would have a

detrimental effect on the local environment. He drops them off with lawyer

Kate (Barbara Crampton), with whom he appears to share a sexual if

not romantic history. He also hopes he can prove the innocence of Miguel (Rigo Garay), a Mexican immigrant whom Hammond is attempting to frame for the recent

killings. Miguel and his entourage of Mexican labourers take the role

usually occupied by gypsies in Universal horrors, that of the interlopers on

the edge of town viewed with suspicion by the locals. Latinos in American

films are often portrayed as a superstitious lot, but Fessenden is keen to

ahve Miguel point out that the werewolf is a white man's myth.

Fessenden's blending of a schlocky monster movie with a drama based around

political corruption on a local level is reminiscent of the early monster

movie scripts of John Sayles (Piranha; Alligator;

The Howling), and Fessenden blends the two as seamlessly as Sayles did before him.

Like Sayles' films, Blackout is something of an ensemble

piece. While there's a definitive protagonist in Charley, we get to spend

time in the company of several supporting characters including the town

sheriff (Joseph Castillo-Midyett), who has also made an enemy of

Hammond by refusing to act as his hired gun, a role filled by Tom Granick

(James Le Gros). There's an entire scene devoted to Sharon and her

new boyfriend (Joe Swanberg, channelling Tim Robbins in

High Fidelity) preparing dinner before a werewolf attack. The various victims are given

enough depth in their scant screen time to make us feel the weight of

Charley's guilt when he tears them apart with his fangs and claws. Talbot

Falls resembles a real inhabited place by the casting of what appears to be

amateur performers in some minor roles. The quality of the performances may

vary, but we feel like we've gotten to know a lot of characters over the

course of the film. Talbot Falls is as richly detailed as Stephen King's

Castle Rock, and a brief epilogue suggests werewolves may not be its only

resident monsters.

Like Sayles, Fessenden imbues his film with political and human drama, but

never loses sight of the fact that he's making a monster movie. And it's

very much a monster movie in the old school sense. There's no hiding the

monster in the shadows nor any attempts to cloud the viewer's mind with

ambiguity. We're shown straight up that Charley is turning into a werewolf!

Lacking the budget or resources to pull off transformations on the scale of

An American Werewolf in London or The Howling, and wisely shunning CG, Fessenden opts for good old-fashioned fake fangs

and fur stuck on his leading man's face. The effects here are pretty much as

they were in 1941's Wolf Man, with Fessenden portraying the transformation

through dissolves, though at one point it's detailed via an animated

sequence that draws on Charley's work as an artist.

If you're one of those boring people who think Jacques Tourneur's

Night of the Demon

is ruined by the reveal of the rubbery monster in its climax,

Blackout may not be for you, and some cynical and jaded modern

viewers may well laugh at the image of the lupine Charley prancing through

the moonlit woods in his shirt and jeans. But Fessenden hasn't made a movie

for those folks. This is a monster movie for people who actually like

monster movies, made by a filmmaker who, unlike some of his peers, doesn't

feel embarrassed about working in the horror genre. Arriving soon after the

release of

an Omen movie that doesn't feature Damien, Blackout is a refreshingly traditional approach to horror,

one that proudly brings its monster out of the shadows.