Review by

Eric Hillis

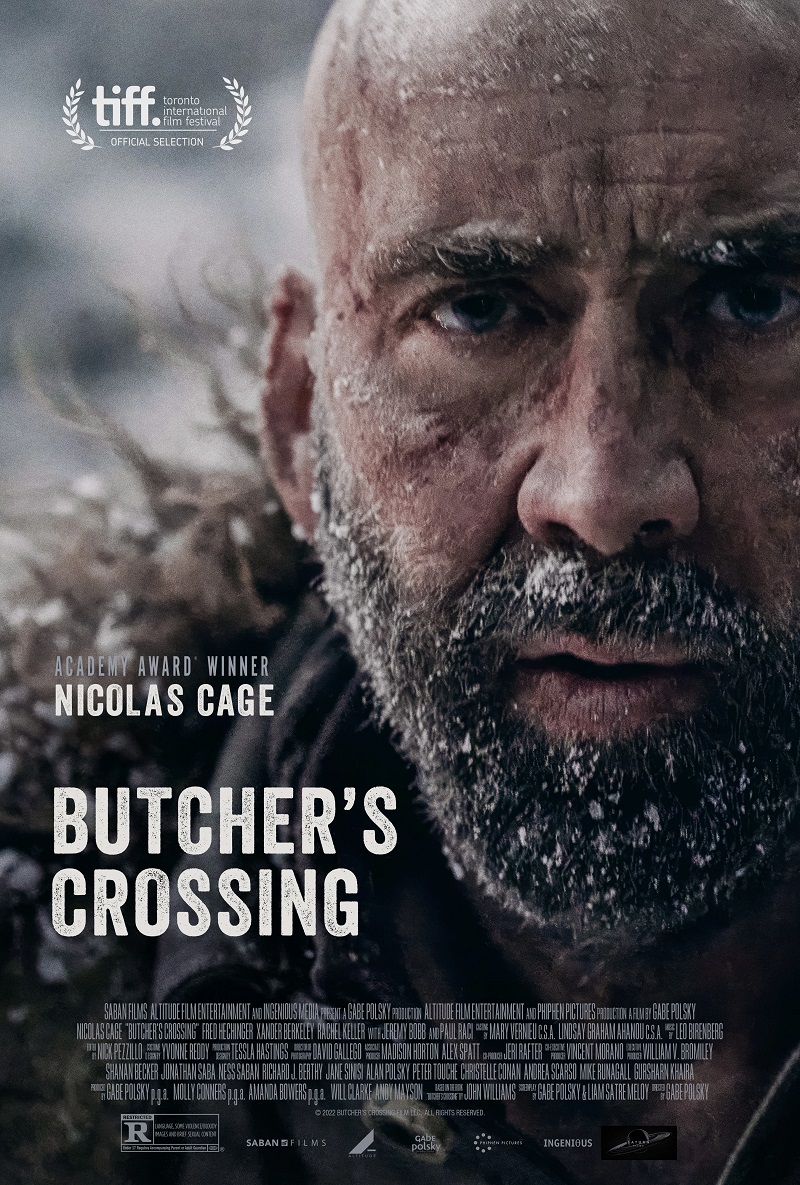

Directed by: Gabe Polsky

Starring: Nicolas Cage, Fred Hechinger, Xander Berkeley, Rachel Keller, Jeremy Bobb, Paul Raci

Nicolas Cage recently made his western debut with the mediocre oater

The Old Way. The flamboyant actor was miscast in a role crying out for a Kevin Costner

or a Jeff Bridges. On paper, director Gabe Polsky's

Butcher's Crossing should be a better fit for Cage's

theatrics, as he plays a literal madman here. Oddly, Cage is so reined in

that he's barely present, something I never thought I'd say about

Hollywood's most exuberant star.

Based on the 1960 novel by John Edward Williams, the film opens in

1874 Kansas. Young minister's son Will Andrews (Fred Hechinger) has

dropped out of Harvard and headed west with romantic notions of seeing the

real America. Looking to join a buffalo hunting party, Will finds himself in

Buffalo's Crossing, a busy trading post for the fur trade. There he finds

Cage's Miller, a gruff buffalo hunter who speaks of a legendary herd

numbering the tens of thousands which he came across in a remote Colorado

valley a decade earlier. Andrews is so enamoured of the hunter that he

agrees to finance an expedition to the valley.

Will and Miller are joined by Miller's elderly companion and cook Charlie

(Xander Berkeley in the sort of role Walter Brennan might have

played), and by Fred (Jeremy Bobb), a boorish buffalo skinner. The

expedition sees the party trek across the desert, where they run low on

water and encounter the usual victims of Indian raiding parties along with a

desperate mother seeking water for her children. Miller's refusal to spare

any of his party's water gives Andrews his first glimpse of the Darwinian

coldness of the west.

When the men finally arrive at Miller's fabled valley, it turns out he

wasn't exaggerating, with buffalo so numerous they paint the landscape

black. Andrews is thrilled as he's taught how to kill and skin the beasts at

the experienced hands of Miller and Fred. But as winter approaches and

Miller insists on staying until every animal in the herd is dead, tensions

begin to rise.

Williams' novel is widely acclaimed as a gruelling, punishing read that

treats its subject matter in unflinching detail. It's easy to see why this

subject would make for a fine literary work in the mould of Jack London or

Joseph Conrad, but its ideas aren't so easy to communicate in the

restrictions of a two hour movie. For a start, Polsky and co-writer Liam Satre-Meloy

struggle to convey time and space. The film relies on characters telling us

how far they've travelled, and it comes as a surprise when such distances

are verbally conveyed. The men seem to arrive at their destination in a

couple of days rather than the months we're supposed to believe it actually

took them. The men talk a lot about being thirsty but rarely look thirsty.

Worried characters talk of the onset of winter but there's no visual sense

of this passage of time save for the eventual snowfall. Even when the men

find themselves trapped in the valley by snow they never quite seem as

visibly affected as you might expect by such conditions. Simple visual

signifiers like steamy breath, huddling around campfires and pulling buffalo

hides close to their bodies are oddly absent, leaving us in no doubt that

the actors are no more than a few feet away from a craft services table and

a warm trailer. When Miller tells us there's no way out of the valley for at

least six months, we don't buy it as the film never shows us any visual

evidence to back up such a claim.

Just as unconvincing as the film's setting are its characters. All four are

little more than archetypes and we never really get to know any of them

despite spending two hours stuck in a valley with this bunch. Andrews is

young and naive. Miller is nuts. Charlie is a drunk (who somehow managed to

bring enough alcohol to keep him sozzled for a full year???). Fred is an

asshole. That's as deep as it gets. The central relationship between Andrews

and Miller is woefully underexplored. You might think the film would lean

into the idea of Andrews viewing Miller as a father figure who represents an

antidote to the stuffy world he left back east, but this dynamic is barely

broached.

The film closes with a string of facts about how the white man almost made

the buffalo extinct and how the animal is now making a comeback thanks to

the preservation efforts of Native Americans. The suggestion is that we've

just watched a movie with a message about conservation, but the film itself

never really gets that idea across. The plight of the buffalo is very much

secondary to that of its human (or inhuman) characters, none of whom are

interesting enough for us to care about.