A TV show production manager contends with personal and professional

issues over the course of a day.

Review by

Eric Hillis

Directed by: Ben Hecking

Starring: Kate Kennedy, Balázs Czukor, Fehiniti Balogun, Jack Morris, Claudia Jolly, Will Brown,

Grace Chilton, Deborah Findlay

Before the advent of camcorders and smartphones, consumers wishing to

preserve moving picture memories had to rely on the Super 8 format. The

grainy texture of the 8mm format has come to symobolise memory and

nostalgia, and when it's deployed by filmmakers it's usually to evoke

both sensations, the classic example perhaps being the credits sequence

for The Wonder Years.

Writer/director/cinematographer Ben Hecking's second feature

Haar is a rare movie shot completely on Super 8 stock.

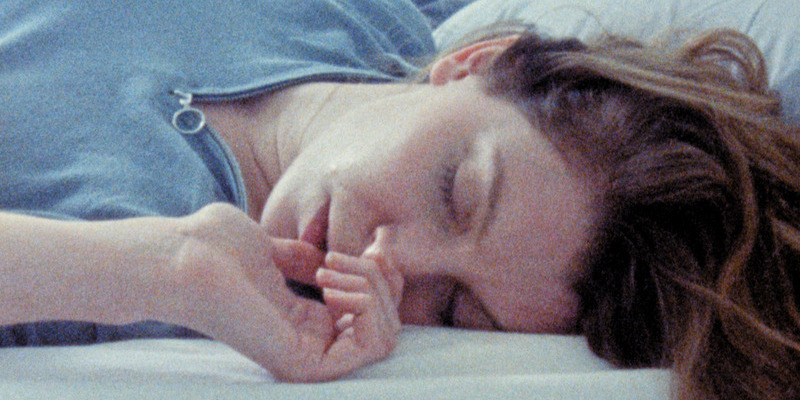

Where the format is usually purposely made to look amateurish, the

striking compositions of Haar remind you that when

utilised by professionals this cheapest of film formats has a quality

lacking in digital.

Though set in the present day, Haar has a nostalgic feel

exacerbated by its use of Super 8. Hecking leaves in flares and

scratches, and even a stray hair in the gate at one point, which gives

it the immediacy of the professional but rushed productions of 1970s and

'80s British TV. The title refers to a designation for a type of mist

that comes in from the sea, and the film equates a fractured memory with

a fog, where some images are clearer than others, and sometimes our eyes

and minds can betray us.

Over the course of a day, Jef (Kate Kennedy) is forced to

confront both her future and her past as she's hit with two bombshells.

Jef is a production manager for a TV show being shot in Budapest, and

with the show having just wrapped, she has a few last minute errands to

run before leaving the city. While contending with her professional

duties, Jef discovers she's pregnant, likely the result of a fling with

the show's leading man, Bill (Jack Morris). A phone call from her

mother brings the bad news of her father's passing following three

successive heart attacks.

Jef is statuesque, Amazonian even, but as they say, the bigger they

are, the harder they fall. She tries to keep it together as she gets on

with her job, but her rigid frame can't disguise the emotions she's

suppressing. On a video call with Bill she conceals the news of her

pregnancy, instead indulging in a mutual masturbation session. She tells

people she wasn't close to her father (who named her Jef because he

wanted a boy), but the doubt on her face tells us she might have been

closer than she thought. Despite her mental state, Jef attends a party,

where a past lover (Fehiniti Balogun) gets some things off his

chest about how her self-absorption makes those around her feel

belittled.

Watching this well-maintained, professional woman slowly mentally

unravel over the course of 80 minutes is like watching a tranquilised

giraffe collapse in slow-motion. In her first leading feature role,

Kennedy is a captivating presence. With her easy-going front and

attractive looks, we can see why Jef is accustomed to being in control

of other people, but also how her aloofness might lead to others being

trampled in her over-bearing presence. We see an early example of this

in how Jef charms a woman who complains that her production left damage

at the location she allowed be filmed, the final look on the woman's

face that of someone trying to figure out if they've just had their

pocket picked.

Like many who exude an air of confidence, Jef is a mess internally. In

a striking piece of acting we watch as Jef takes a rare breather to sit

on a park bench and eat a sandwich. Hecking holds his camera on

Kennedy's face as it betrays a myriad of thoughts and emotions as though

Jef is trying to compartmentalise her troubles in the manner she might

deal with various work issues. Though we only hear her voice,

Deborah Findlay is subtly affecting as Jef's distraught mother,

and her interactions with her distant daughter are almost word for word

those I had with my own mother when she broke the news of my father's

passing in similar circumstances.

Haar is a tender tale of a tough woman. With its

protagonist traversing a scenic European city, it has the feel of

Linklater's Before Sunrise, but instead of asking the audience if two protagonists might fall in

love, it proffers the question of whether one woman might learn to love

herself. In Kennedy's Jef we're reminded that self-absorption is often a

close cousin of self-doubt.