Review by

Eric Hillis

Directed by: Robin Hardy

Starring: Edward Woodward, Christopher Lee, Britt Ekland, Diane

Cilento, Ingrid Pitt

Jean-Luc Godard called his

King Lear

"A picture shot in the back," referring to the difficulties of working

with Cannon Films. 1973's The Wicker Man might be

described as a film buried twice, but ultimately resurrected. On its

initial release it was buried as the b-picture in a double bill with

Don't Look Now and was quite literally buried when its

negative was used as landfill for the then under construction M3 (either

accidentally or as star Christopher Lee believed, quite on

purpose).

Along with such poor treatment, the film was originally put out in a

butchered cut that disrupted its narrative timeline. A couple of decades

later, Roger Corman revealed that he was in possession of a print of

director Robin Hardy's original cut, leading to the subsequent

release of a director's cut. In 2013, some more footage was discovered

and a "Final Cut" was released to celebrate the film's 40th anniversary.

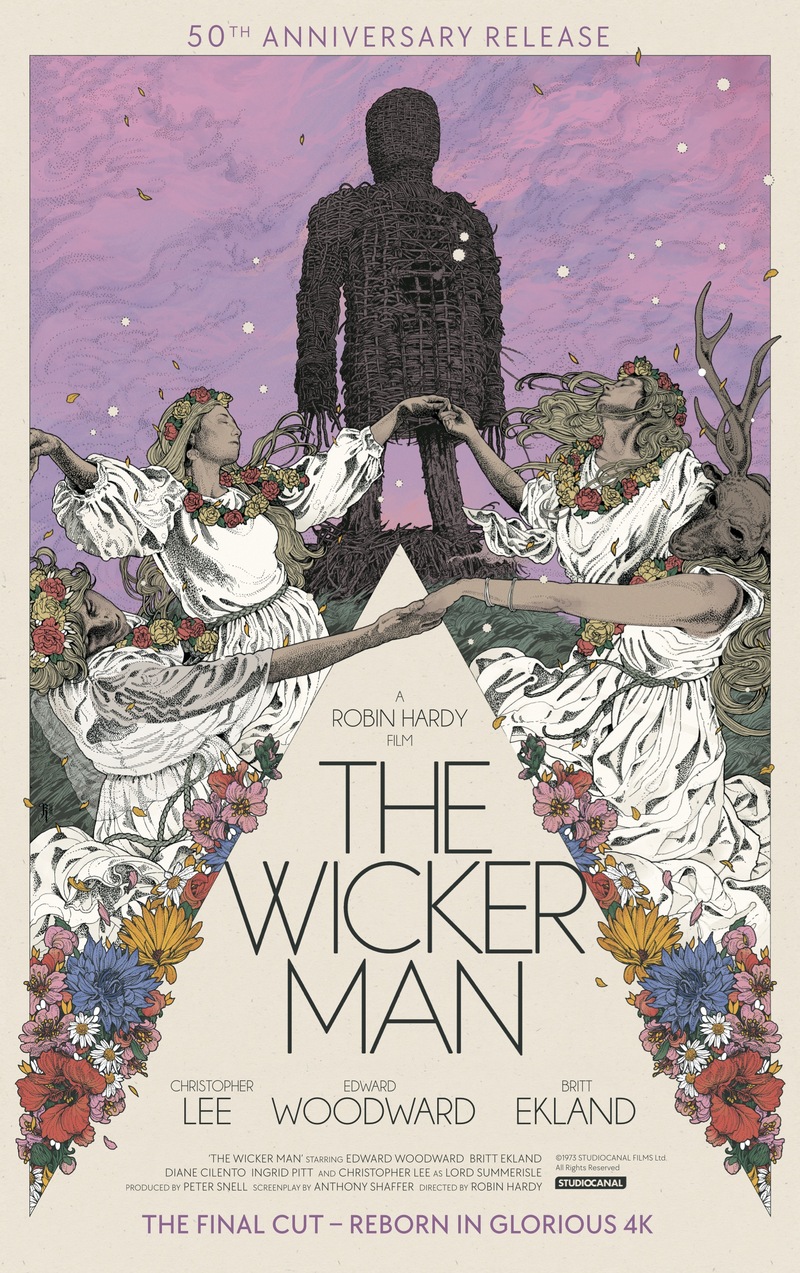

No more footage has been uncovered for this 50th anniversary release,

but the movie has been restored in 4K and now looks better than

ever.

The early 1970s was something of a hangover from the swinging '60s, and

this was heavily reflected in Britain's genre cinema of the era. At the

time there was both a mistrust of the hippy counterculture brought on

largely by the Manson murders, and of institutions and the elite,

ushered in by various scandals. There was also a growing divide between

urban and rural folk, who increasingly viewed each other with a mutual

suspicion.

All of these factors come to a glorious head in

The Wicker Man. Some viewers will take the side of its Christian protagonist, others

will sympathise with its pagan antagonists, but the film is neither

critical nor supportive of either faction. If it's critical of anything

it's of those who wield power, whether that be Edward Woodward's

fascistic cop Sgt Howie or Lee's Lord Summerisle, who rules the small

Scottish island as a dictator. Both can be viewed as colonial

interlopers. Howie has arrived from the mainland and displays contempt

for the ways of its people. Summerisle's grandfather was essentially an

English gentrifier who rocked up to the island and replaced its

Christian traditions with "the old ways."

Howie travels to Summerisle after receiving an anonymous letter

concerning the disappearance of Rowan Morrison, a 13-year-old girl whose

existence is initially denied by the islanders, including the woman

Howie believes is the girl's mother. As Howie investigates further it

becomes clear the wool is being pulled over his eyes. He learns that

Rowan died several months earlier, but finds that her coffin contains

only the corpse of a hare.

All the while, Howie grows increasingly contemptuous of the sexual

freedom practiced by the islanders, who sing bawdy songs and copulate

openly in public orgies. As Jack Nicholson's character says in

Easy Rider of men like Howie, "They hate you because you

represent freedom." Howie is essentially a fascist enforcer for both the

police force and his Christian God, unquestioning of either. The people

of Summerisle are really no better though. They've fallen for

Summerisle's pagan blarney, which allows him to rule from the big

house.

I doubt there's anyone who is unfamiliar with the film's climax, but

spoiler warning from here if so. We

learn that Howie has indeed been lured to Summerisle under false

pretences. The previous year the apple crop failed and Summerisle

believes only a human sacrifice to appease the Gods can ensure this

year's crop is a success. Howie is chosen because he's a virgin, having

resisted the charms of Willow (Britt Ekland), the landlord's

daughter at the island's raucous pub. In one of the film's most

memorable scenes, Willow sings and dances naked in her room while Howie

sweats profusely next door. Like Charlie in

Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, Howie is subjected to a purity test, though his "reward" is less

enticing.

The title of course refers to the giant structure in which Howie is set

to meet his maker. Woodward's lines were painted in giant letters on

bedsheets on a nearby cliff, and the actor's distant gaze as he reads

from them gives the effect that he's looking for his God in his time of

desperation.

The Wicker Man is a movie that benefitted greatly from

both chance and improvisation. The latter can be seen when Howie enters

the graveyard and fashions two pieces of wood into a cross, a bit of

business that wasn't in the script but was pounced upon by the

instinctive Woodward. Despite being set around Mayday, the film was

actually shot in October. When Howie arrives on the shores of Summerisle

it's clearly a blustery autumn day, as is the case with the closing

scenes on the island's coastal cliffs. The scenes on the island's

interior however could easily have been shot in May, and the combination

of beaming sunlight and the colourful flora give the impression that the

island is like a fruit itself, its ripe insides masked by a hard peel.

Perhaps the greatest piece of luck befell the film when the head of the

giant wicker man collapsed at just the right time to reveal the rising

sun in the distance. For 21st century viewers, this shot now has an

eerie resonance with the collapse of the World Trade Center.

All three cuts are included on Studiocanal's re-release, but the Final

Cut is probably the best option. The theatrical cut compresses the

events to two days rather the three of the other cuts. There's a sense

that Howie is being both tested and taunted by the islanders that's

somewhat lost in this two-day version. Perhaps the biggest difference

concerns the use of Willow. In the theatrical cut she performs her

seductive dance on the first night. It's far more effective in the other

cuts, which move it to the second night, when Howie has had time to

expose himself to the island's libertine ways. The director's and final

cuts also feel more democratic in giving us a bit more time to soak up

the ways of the islanders and make our own minds up as to who is crazier

here: the islanders who believe committing murder will save their way of

life, or the devout Christian who commits himself to a God whose

existence he sees no proof of?