Review by

Eric Hillis

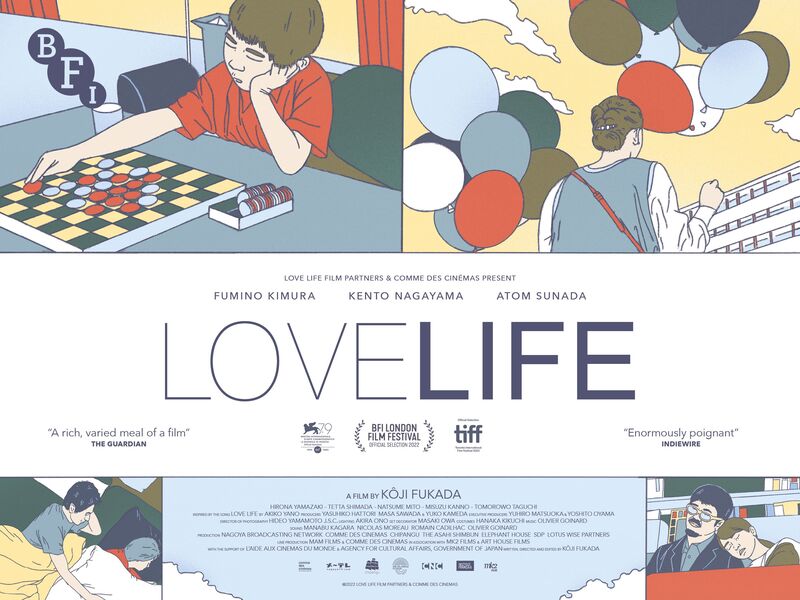

Directed by: Koji Fukada

Starring: Fumino Kimura, Kento Nagayama, Tetta Shimada, Atom Sunada,

Hirona Yamazaki

A Koji Fukada movie centred on a devastating incident involving

a child and the burgeoning relationship between a quietly unhappy wife

and a taciturn man who may not have her best interests at heart –

haven't we seen this one already? While Fukada's latest,

Love Life, shares some key plot elements with his masterpiece of misery,

Harmonium, the two films couldn't be further apart in tone.

Harmonium is a grim but rewarding film about the cruelty

life sometimes inflicts on those who least deserve it.

Love Life is essentially treading the same ground but it

does so with a full, if heavy heart. With its melancholic humour, tinkly

piano score and profound human insight, Fukada's latest might be

mistaken for the work of his compatriots Hirokazu Kore-eda or Naomi

Kawase.

Ever since Ozu's teapot, film scholars have been keeping an eye out for

the use of specific props in Japanese films. Fukada presents us with one

for the ages here in the form of a compact disc hung outside the

apartment of our protagonists. The disc reflects the sun in a manner

that is utilised to brilliant effect in a revelatory scene later on, but

as the movie opens it's simply casting dappled light into the living

room of young couple Taeko (Fumino Kimura) and Jiro (Kento Nagayama), which they share with Keita (Tetsuda Shimada), Taeko's

eight-year-old son from a previous marriage to Park (Atom Sunada), a deaf Korean immigrant who abandoned his wife and son four years

prior.

It should be a day of celebration. Keita has won a regional

championship in the boardgame Othello, and it's the 65th birthday of

Jiro's father, Makoto (Tomorowo Taguchi). The celebrations are

tempered, first by a cruel metaphor deployed by Makoto regarding the

inferiority of second hand fishing reels directed at Taeko, and then by

the death of Keito, who knocks his head and drowns in the bath Taeko

forgot to drain.

The immediate scenes make for starkly realistic depictions of those

difficult days in the wake of a loss. There's no rule book for how one

should behave or grieve at such a time, but everyone has their own

ideas. Previously an ally to Taeko, Jiro's mother (Misuzu Kanno)

is horrified at her daughter-in-law's desire to bring the boy's body

home for a night. Surprisingly, it's Makoto who defends Taeko's wishes.

Tellingly, Jiro just stands by uselessly.

When Park makes a surprise and traumatic appearance at his son's

funeral, it leads Taeko to reconnect with her former husband. At first

she tells herself it's simply for professional reasons. Taeko is a

social worker and the only one who can communicate with Park through

Korean Sign Language in order to process his benefits – in an ironic

case of nominative determinism, he's been living in a park for the last

two years. But the act of speaking in this way reminds Taeko of the

unique relationship between herself, Park and their late son. Early on

we witness a playful moment in which Taeko and her boy speak in KSL to

make a joke at Jiro's expense, and as the film progresses Jiro is once

again shut out as Taeko and Park speak a language he isn't privy to.

This leads Jiro to reconnect with a past lover himself.

Love Life is the very opposite of what might reductively

be labelled a "message movie." There's nothing didactic here, no

instructions imparted to the viewer from a wise filmmaker. Rather Fukada

knows that life is messy and sometimes there simply aren't any ready

made answers. With the exception of Taeko, practically every character

performs an action or gesture at some point that threatens to signify

them as the villain of the story, only to redeem themselves a couple of

scenes later. Everyone is a trainwreck, unable to figure out how to deal

with the situation that's unexpectedly presented itself. All that is,

save for Taeko, who refuses to move forward and instead embraces her

grief. In an understated but affecting scene, Taeko clings onto her

son's Othello board during a minor earthquake, determined that its

pieces remain in place from the final game she played with the boy.

She's unable to take a bath until she's accompanied by the silent but

oddly comforting Park. While those around her tell her she needs to move

on, Park is wise (or manipulative) enough to tell her the

opposite.

The disabled have been ill-served when it comes to screen

representation. They're usually portrayed as pathetic at worst, angelic

at best. Park marks a giant leap forward in terms of how disabled people

might be represented. He's certainly not pathetic, even if Taeko is

convinced he can't function without her, and he's far from angelic. He's

as messy and duplicitous as anyone else. It shouldn't feel revolutionary

that a movie dare to portray a disabled person as layered and difficult

to read, yet this is how it feels to watch Park act as a curious blend

of antagonist and saviour.

I've often felt Japanese dramas have much in common with classic

Hollywood westerns, particularly those of John Ford. They're both

populated by people who can't express their emotions, who often bury

themselves in their work to escape emotional pain. In the western, key

dialogue scenes often play out on horseback, allowing for a lack of eye

contact, and many Japanese filmmakers stage their own key scenes with a

similar parallel staging. Fukada seems to pick up on this when Jiro's

ex-lover remarks about how he never looks anyone in the eye when he

speaks. Another western trope is brilliantly repurposed here when the

camera follows Taeko from her office across the street to the building

where Park is seeking help, reminding us of all those climactic

set-pieces in which the western hero crosses the dusty street to meet

his fate head-on (John Carpenter did this to great effect at the climax

of

Halloween). As East meets West in this fashion we're reminded that love and life

are universal, and while we sometimes might wish to avoid them as

obstacles, we need to face them both down if we're to carry on.