Review by

Eric Hillis

Directed by: Christopher Nolan

Starring: Cillian Murphy, Emily Blunt, Matt Damon, Robert Downey Jr, Gary Oldman, Casey Affleck,

Florence Pugh, Benny Safdie, Michael Angarano, Josh Hartnett

Hollywood loves the biopic, probably because it's a genre that combines

name recognition with potential awards glory. But very few biopics are

worthwhile, and most leave you wishing you had just watched a 50-minute

PBS or BBC documentary rather than a bloated feature film. The few

worthwhile biopics tend to hone in on a specific period of their

subject's life. Christopher Nolan's

Oppenheimer hones in on two periods of physicist J. Robert

Oppenheimer's life, and it often feels like two different movies edited

together. One is a riveting wartime thriller, the other a rather flat

post-war courtroom drama. If we can split the atom, maybe some intrepid

amateur editor will at some point in the future split Nolan's movie in

two and extract a very good 90 minute movie from its current three

hours.

Taking its cues from one of the few great biopics – Milos Forman's

Amadeus – Oppenheimer gives us its own

version of Mozart vs Salieri. The Mozart figure is of course

Oppenheimer, played by Cillian Murphy in his biggest role to

date. Pitted against him is Robert Downey Jr's Salie…, sorry,

Lewis Strauss. In the film's less engaging timeline it's 1954 and

Strauss is head of the US Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). Oppenheimer

finds himself the subject of a kangaroo court determined to expose him

as a communist and strip him of his security clearance. We're told

Strauss has it in for Oppenheimer, but we're never really shown why this

might be. This is a recurring problem throughout Nolan's film. In its

race to pack in as much information as possible in its three hours we're

told a lot of things about a lot of people, but shown very little to

back up such statements.

The far more exciting portion of Oppenheimer is devoted

to the race to develop the atom bomb before the Nazis. I have a lot of

issues with Nolan's filmmaking but this sort of ticking clock narrative

is something he does better than most. It's made clear that when

Oppenheimer and his fellow boffins embarked down this path they had no

idea what the results might be. There's a chance that setting off an

atom bomb might cause a chain reaction that would essentially destroy

the world. It's a near zero chance mind, but as one character remarks,

"Zero would be nice."

What's impressive about how Nolan constructs this sequence is that by

the simple fact that we're sitting in a cinema watching

Oppenheimer, we know the world wasn't destroyed when that key button was pushed,

yet it's incredibly tense regardless. Nolan puts us in the shoes of the

men about to make that potentially fatal call, and our own hindsight

goes out the window. Those scientists knew there was a chance, however

small, that it could all go horribly wrong, and their apprehension is

palpable.

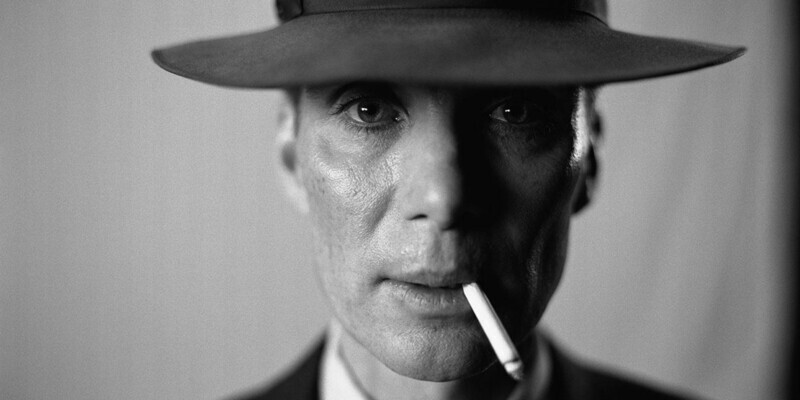

Nolan's two main weapons in selling this idea are Murphy's eyes, two of

the most expressive in modern cinema. Brash at first in his younger

days, Oppenheimer becomes more insular and taciturn as the film

progresses and the fate of the world weighs down on his scrawny

shoulders. But Murphy's eyes tell us just what he's going through. As

the film progresses and Oppenheimer becomes more distraught and

guilt-ridden, Murphy's eyes take on the appearance of a pair of ghostly

children peering out the windows of a crumbling Edwardian home. When

Oppenheimer receives some bad personal news and breaks down, you get the

feeling it's a relief of sorts, a distraction from his role in the

potential destruction of the world.

Supporting characters are far less enriched however. It's easy to mock

Nolan's ongoing struggle to write a compelling woman but the two female

figures here – Oppenheimer's wife Kitty (Emily Blunt) and Jean

Tatlock (Florence Pugh), a young communist he has an affair with

– are as bad as any he's written. Kitty is particularly puzzling,

portrayed as a weird mix of sozzled-era Liz Taylor and Lady Macbeth, and

Blunt appears to be begging for some sort of clear direction throughout.

Tatlock seems to exist merely to get some steaminess into the drama. In

one of the unfortunate cues Nolan takes from '90s Oliver Stone here,

Kitty imagines a naked Tatlock straddling her husband as he's being

grilled by McCarthyites. It's the cringiest thing I've seen in some

time.

Nolan likes to dial things up, and the cringe factor is no exception

here. The by now groan-worthy biopic trope of making casual reference to

something that will become relevant at a later stage is employed several

times here: "My favourite spot to get away…Los Alamos," "And that man

was…John F. Kennedy" etc. At one point Oppenheimer is asked to translate

a sanskrit copy of the Bhagavad-Gita, and it just happens to randomly

open on the page bearing the "destroyer of worlds" passage.

The cringe extends to some of the supporting performances. To balance

some great turns – Matt Damon's Leslie Groves,

Josh Hartnett's Ernest Lawrence, Downey Jr's Strauss – we get

Gary Oldman hamming it up as Harry Truman and

Kenneth Branagh and Benny Safdie butchering European

accents. In this age where Hollywood purports to be so concerned with

representation, why are we still getting Anglophone actors delivering

Dr. Strangelove caricatures of continental Europeans?

Much of the marketing around Oppenheimer has focussed on

its use of the 65mm IMAX format and Nolan recreating the Trinity test

explosion without the use of digital effects. Considering the bulk of

the movie consists of close-ups of blokes talking, it's hard to argue

that this is a movie that needs to be seen on the biggest screen

possible (I can't believe this is bumping

the latest Mission: Impossible

from IMAX screens). "I bet that explosion is something else though,

right?" you might ask. Well, it's pretty underwhelming. It can't hold a

candle to the nuclear blast from the incredible eighth episode of

Twin Peaks: The Return, and I've seen better explosions on TJ Hooker.

A common complaint directed at recent Nolan films has been the

inability to clearly hear dialogue, given his penchant for drowning it

out with screeching scores. That's thankfully not an issue here. Given

how heavily Nolan relies on dialogue to tell this story, I don't think

even he would have risked pissing off audiences once again in this

manner. But the score, by Ludwig Göransson, is nevertheless

intrusive, especially in the 1954 portion. Though this segment is

essentially an intimate courtroom drama, the composer scores it as

though he's still watching the Los Alamos portion. The effect is like

watching an episode of Matlock while blaring Stravinsky's

The Rite of Spring through your speakers.

Perhaps Oppenheimer's biggest flaw is how little insight it gives us into the man himself.

All I knew about Oppenheimer beforehand was that he was the key figure

in developing the atom bomb and that he felt pretty bad about this for

the rest of his life. Having watched the movie I still don't really know

anything more about the man.