Review by

Eric Hillis

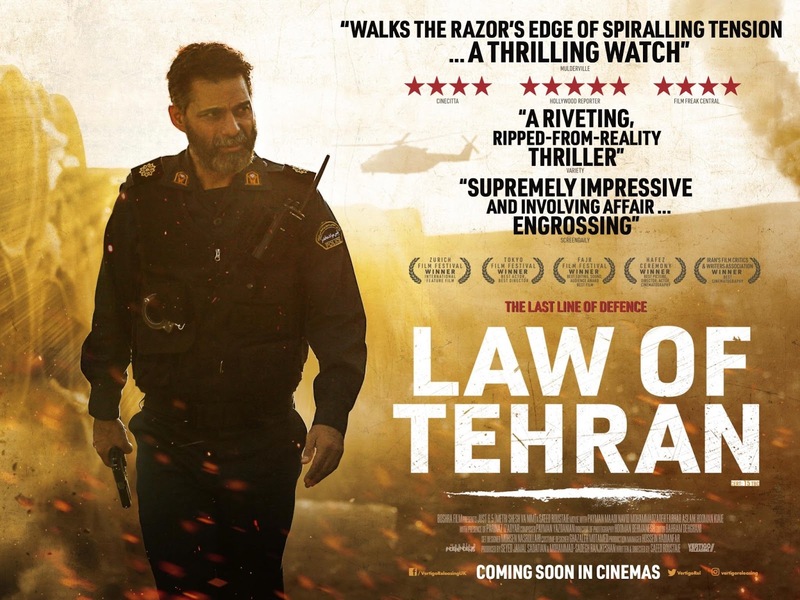

Directed by: Saeed Roustaee

Starring: Payman Maadi, Navid Mohammadzadeh, Parinaz Izadyar, Farhad Aslani, Houman Kiai, Yusef

Khosravi

There's a memorable sequence in the 1985 Hong Kong action comedy

Police Story in which the heroic cop played by Jackie Chan

engages in a car chase through a shanty town. Homes constructed of

plywood and corrugated iron are destroyed as the cop and the crims he's

pursuing drive their cars through them with no regard for human life. In

1980s Hong Kong, as in much of the world, the sort of people who live in

such an area were considered subhuman, so who cares if a few of them get

run over if it leads to the arrest of some villainous drug dealers?

Attitudes have thankfully changed a little in the intervening decades,

and so when Iranian writer/director Saeed Roustaee stages a

similar scene in his cops vs drug dealers thriller

Law of Tehran, it has a very different effect. As we watch dozens of heavily armed

cops - resembling, as cops so often do today, soldiers rather than

guardians of the peace – dismantle poorly constructed homes, rouse

junkies from their slumber and herd the residents like cattle for the

slaughter into awaiting vans, it's impossible to root for the cops.

What's so fascinating about Law of Tehran is that it's a

film that doesn't want us to root for either the cops or the dealers

they pursue, but it strives for us to understand both of them. It's a

movie that functions as both an anti-drug PSA and a critique of the war

on drugs.

Cop movies are rare today because the public has lost its appetite for

movies that ask us to sympathise with the police. The idea of the police

as a group whose job is to serve and protect the public has been exposed

as a fallacy in recent years as it's become clear the true role of the

police is to protect the authorities and themselves, not the public. The

classic image of the "bobby on the beat," doffing his hat and smiling at

passersby, stopping to tickle babies in prams and helping old ladies

cross the street is now the stuff of fantasy. Picture a cop now and you

most likely picture a musclebound, tattooed thug dressed like a member

of the SAS, their face covered so they can't easily be identified. With

an increasing number of so-called democratic countries introducing new

laws designed to crack down on protest, you're more likely to find

yourself in trouble with the police than ever be aided by them. Cops are

now our enemies, and we're theirs. The police once attracted the sort of

people who might have gone into nursing, those who wanted to help

others. Now it mostly attracts angry men who want a licence to clobber

you over the head. How did it come to this?

Anyway, I'm rambling, but suffice to say we're not going to see the

sort of pro-cop movies of the 1980s and 1990s again.

Law of Tehran suggests however that we might be set for a

revival of the more nuanced police thrillers of the cynical 1970s.

Movies with villains who were indeed scumbags, but whose anti-hero cops

were so despicable you were forced to root for them through gritted

teeth. Roustaee gives us an anti-hero cop that could have been plucked

straight from a '70s Hollywood thriller, or one of their more lurid

Italian poliziotteschi cousins. Samad (Payman Maadi) is the

classic cop who will do anything to get his man, even if it means using

his own men as pawns. The man he wants to "get" is drug baron Naser (Navid Mohammadzadeh), who grew up in the sort of shanty town we witness torn apart but now

resides in a lush penthouse overlooking the Iranian capital.

Law of Tehran feels remarkably well researched. There are

details here I've never seen in any other cop movie, which seem the

result of talking with people who have lived this life for real. Little

details like a suspect attempting to tear his fingerprints off by

rubbing them against the wall of a jail cell before he can be processed.

Details like three morbidly obese men being employed as drug mules due

to the airport x-ray scanner's inability to see the hidden drugs through

their layers of fat. Details like the petty criminal who purposely gets

himself jailed every night so he can sell drugs and other goods to

desperate inmates. I've never seen a thriller so invested in the process

of temporary incarceration as Law of Tehran, with hundreds of men piled into overcrowded cells, the stench of

urine and desperation almost wafting off the screen.

At the halfway point, when Naser is apprehended, he takes over as the

film's lead character from Samad. We watch as he uses his charisma and

imposing nature to take over the jail and begin the process of getting

himself free. It's a striking performance by Mohammadzadeh, one which

recalls the classic 1930s gangster pics of Jimmy Cagney. Like the

characters Cagney played, Mohammadzadeh's Naser is a brute who has

become obsessed with wealth, but he hasn't lost his ties to his

community. He pleads the case that his upbringing left him no choice but

to turn to crime, and the film offers us a glimpse of a potential future

Naser in 12-year-old Vahid (Yusef Khosravi), who has been coerced

by his drug dealing father into taking the rap for his old man. As we

watch a judge coldly condemn the child to a juvenile prison while

smirking at some unseen text message, any support we might have had for

the war on drugs quickly erodes. At the same time, Naser is such a

scumbag that we want him brought to justice.

Law of Tehran doesn't make it easy for us in terms of

simplistic ideas of good guys and bad guys, but it makes it easy to

understand why these men act the way they do.

Along with some striking set-pieces like the opening foot chase and the

shanty town raid, the film features scenes of men bickering and debating

in stuffy rooms that are equally thrilling. The way Samad and his fellow

cops treat each other with contempt recalls the narcissistic real estate

salesmen of Glengarry Glen Ross. Interrogation scenes crackle with the energy of the legendary "The

Box" scenes of '90s cop show Homicide: Life on the Street. The difference here is that we know the suspect is guilty, they've

practically confessed, but they're now using the opportunity to find a

way out, be it through bribery attempts or threats.

After over two hours of brutality and cynicism, the film offers a late

respite as Naser is visited by his family, deported from Canada due to

their connection with the mobster, their lives thus ruined. He watches

as his young nephew shows off gymnastic moves, and like Cagney at the

end of Angels with Dirty Faces, we see in his face that he now realises how many lives he's ruined.

Perhaps this acknowledgement makes him less of a villain than Samad, who

doesn't seem to care about the devastation caused by his side of the

war.

Law of Tehran initially played in festivals back in 2019

under the title "Just 6.5", a reference to 6.5 million, the number of

drug addicts in Iran, a striking figure for a population under 90

million. If the definition of madness is doing the same thing over and

over and expecting different results, Iran's war on drugs, like everyone

else's, is lunacy.

Law of Tehran is on Prime Video

UK now.