Review by

Eric Hillis

Directed by: Mario Martone

Starring: Pierfrancesco Favino, Francesco Di Leva, Tommaso Ragno, Aurora Quattrocchi, Sofia Essaidi

A candidate for the most over-used premise in movies over the past

couple of decades is that of a protagonist returning to their hometown

and wrestling with a past they left behind. You see it played straight

in countless American indies. You see it played for laughs in almost

every Hallmark Christmas movie. It fuels many a British gangster movie,

with hard men returning to "the manor" after time in jail. It's recently

begun to crop up as a staple of queer cinema, with adult gay characters

returning to their childhood home and attempting to reconcile with a

previously disapproving family.

Adapted from a novel by Ermanno Rea, Mario Martone's

Nostalgia is the latest drama to adopt this set-up. In

many ways it's a mixture of the straight drama, the gangster movie and

possibly even the queer cinema examples listed above. What makes it

stand out from its crowded field is its explicit sense of place, with

the Naples neighbourhood of Rione Sanita brought vividly to life.

It's to this beaten down but defiant area that Felice (Pierfrancesco Favino) returns after a 40-year absence, most of which has been spent in

Cairo where he has become a successful businessman with a beautiful

Egyptian wife (Sofia Essaidi). On his return, Felice is surprised

to find that little has changed in the neighbourhood. On one hand this

brings back good memories of his youth, but on the other it reminds him

of why he left.

Through flashbacks we learn of the teenage Felice's wild youth.

Influenced by a tough, charismatic friend, Oreste (played as an adult by

Tommaso Ragno), Felice became involved in petty crime. It's

ultimately revealed that a more serious crime led to Felice fleeing his

home for Africa. In the intervening years Felice has converted to Islam,

but he can't shake his Catholic guilt and feels compelled to meet with

Oreste to explain why he abandoned him.

When Felice unofficially confesses his past sins to the local priest,

Don Luigi (Francesco Di Leva), the cleric blows his top in anger

that Felice has compassion for Oreste, who now controls all the criminal

activity in the neighbourhood and has earned the nickname "Badman." But

the priest sees Felice's interest as a way of exposing Oreste and

manipulates the returning man into making his presence known, placing

Felice in potential danger. Don Luigi also views Felice as something of

a special project, coaxing him into drinking wine in the hopes it might

lure him back into the Christian fold.

Felice grows paranoid that Oreste may want him dead to maintain the

silence he's maintained through his absence over the last four decades.

That silence would seem to refer to the crime the two teenagers were

involved in, but flashbacks in which the boys frolic naked in the sea

and hold tightly onto one another while riding Felice's moped imply they

may have a secret of another kind that Oreste doesn't want getting out

(I have to admit that this may not be the intention of Martone

whatsoever, that it's simply a case of an emotionally stunted Irish

critic reading too much into the comfortable affections of two Italian

men).

With its triangle of gangster villain, reformed criminal protagonist

and streetwise priest middleman, Nostalgia has a central

dynamic straight out of a 1930s Warner Bros gangster picture. But

there's no rat-a-tat dialogue or gunplay here, rather a slow burn drama

in which a man slowly seals his fate by tempting it. The film appears to

owe a minor debt to

Andrei Tarkovsky's 1983 Italian-set drama of the same name, with a sequence in which Felice imagines his wife as the African

princess whose visage he sees painted in a catacomb (Tarkovsky's

protagonist has a similar experience with the Virgin Mary). Scenes in

which Felice wanders his neighbourhood have an Antonioni-esque quality

at times, with Felice made to look inconsequential by the surrounding

architecture.

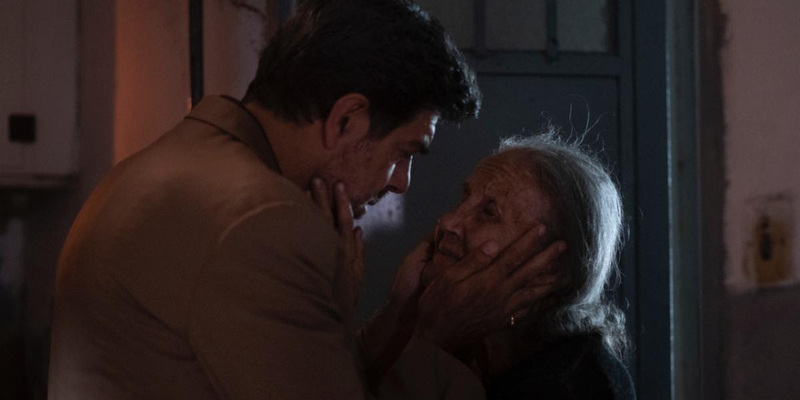

Oreste is portrayed as a Colonel Kurtz figure, or a less charismatic

Harry Lime, spoken about in hushed tones by a populace that lives in

fear of his power. But in giving us glimpses of Oreste before his

eventual encounter with Felice, Martone demythologises the figure,

showing him as a crumbling, aging man with a haunted look in his eyes,

reflected in the disdainful way Don Luigi speaks of him. By the time

Felice has journeyed up the metaphorical river and into Oreste's heart

of darkness, we understand why Felice doesn't fear Oreste the way

everyone else seems to. After this pivotal meeting, much of the

remaining film becomes redundant, leading to a predictable ending that

some might view as cynical for cynicism's sake.

Along with Felice, Oreste and Don Luigi, the fourth wheel in this

narrative FIAT is the neighbourhood of Rione Sanita. By the end of the

movie you feel as if you know every alleyway in this place. Martone uses

its geography, with its narrow streets and moped traffic to create the

paranoid sense that trouble can emerge from any doorway or from around

any corner at any time. But we also understand why Felice feels at home

in this vibrant place where nobody is a stranger and a plate of

meatballs and pasta awaits a visitor on every kitchen table. Felice may

be in danger here, but it's where he belongs.