Review by

Eric Hillis

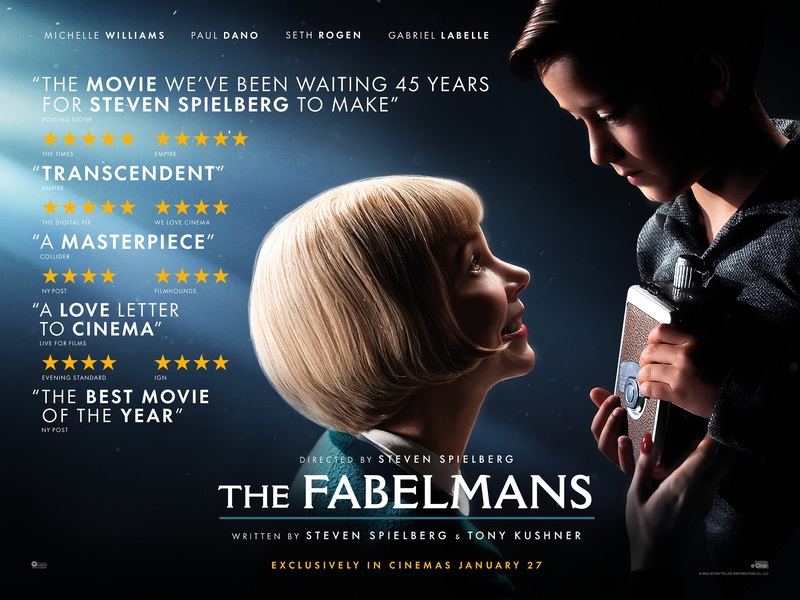

Directed by: Steven Spielberg

Starring: Gabriel LaBelle, Michelle Williams, Paul Dano, Seth Rogen, Judd Hirsch, Julia Butters,

Jeannie Berlin

When asked if she would ever write an autobiography, the critic Pauline

Kael's response was that to do so would be redundant as the thousands of

film reviews she had penned essentially constituted a biography. If a

filmmaker is in the privileged and now all too rare position of being

able to make the movies they actually want to make, they'll leave behind

a body of work that will serve as a biography of sorts.

Steven Spielberg is one of the few mainstream filmmakers who

found himself in such an envious position, and his life can be found in

his work. If you want to learn about Spielberg's mother, watch

Close Encounters. If you want to learn about his father, watch E.T. If you want to learn about Spielberg's early life as a young genius,

watch Catch Me if You Can. Ironically, those three movies will tell you more about Steve and his

parents than The Fabelmans, which serves as an auto-biopic of the great director's youth, the

story of how Steven Spielberg became Spielberg.

Young Steven is represented here by Sammy Fabelman, whose parents –

Burt (Paul Dano) the engineer and Mitzi (Michelle Williams) the pianist – represent the two sides of Spielberg the filmmaker, the

innovator who advances his form while never losing sight of humanity (at

least that's the generous view of Spielberg). We meet young Sammy in

1952 as Burt and Mitzi take him to see

The Greatest Show on Earth, his first trip to the cinema. The kid experiences something akin to a

spiritual awakening and is particularly affected by the movie's train

crash scene. Wishing to recreate the spectacle, he talks his Dad into

buying him a train set, which he insists on crashing. Left-brained Burt

can't understand what's up with the kid, but right-brained Mom sees

artistic potential and purchases Sammy his first camera, which he uses

to film his own train crash.

Sammy doesn't just set up the camera and shoot the crash – he employs

multiple camera setups. It's at this early point that we're forced to

call bullshit on Spielberg's recollections of his own prodigious

talents. We're supposed to believe that a kid who just saw his first

movie already understands the concept of editing?

The Fabelmans continues to be something of a masturbatory

ego trip as Sammy enters school and starts to shoot movies that look as

technically impressive as anything coming out of Hollywood at the time.

I'm sure the movies Spielberg shot as a teen were hugely impressive, but

they weren't lit by Janusz Kaminski. If Spielberg is so impressed

by his own early work why didn't he just use the real movies here rather

than hiding them away in a vault, as is the case in real life? Real life

isn't enough for Spielberg; everything must be heightened, exaggerated,

over the top. In his best work, Spielberg made life big, but too often

he tries to make his movies bigger than life. It's okay if your teen

movies were amateurish Steve, you were a kid. They don't have to look

like they were made by Sergio Leone to impress us.

Spielberg was the first filmmaker to popularise the idea of the Special

Edition with his rerelease of Close Encounters. That version of the movie – which added pointless footage of Richard

Dreyfuss aboard the alien craft – was an early indication that Spielberg

either doesn't understand what makes him such a great filmmaker or he

doesn't have faith in his audience to grasp a concept unless he hits us

over the head with it. By taking us inside the alien spaceship,

Spielberg diluted much of the magic of that film's ending, and it's now

widely held that the best version of

Close Encounters isn't the Special Edition or even his

later director's cut, but the original theatrical cut. Back then there

were still people in Hollywood who were bigger than Spielberg, who could

rein in his worst tendencies, but those days are long gone and now every

Spielberg movie is a Special Edition.

With The Fabelmans, Spielberg gives his own life a Special Edition. Spielberg is Han Solo

and everyone else is Greedo, and this time Greedo shoots first. Any

rough edges of Spielberg's youth have been sanded off. We don't really

learn anything about him other than he's a genius (and a great kisser

apparently!). We don't learn much about his parents because they're such

one-note portrayals of the archetypal cold, logical father and the too

beautiful for this world, away with the fairies mother.

The Fabelmans is The Tree of Life for

dummies. With that movie, Terence Malick was honest in his

recollections, or lack thereof, of his childhood and his parents, and as

such his film has a dreamlike quality where no easy answers are given.

Not so here. You get the sense that this is Spielberg rewriting his

youth rather than recollecting it. When he enters a Californian high

school and encounters anti-semitism, none of it rings true. I don't

doubt Spielberg experienced religious bigotry but I very much doubt it

was at the hands of cartoonish jocks who seem to have stepped out of a

1960s comic book (one of them is call Chad, I shit you not!). Is this

Spielberg's recollection of his childhood or of the Spider-Man comics he

read? Is Chad a real-life figure or is he confusing him with Flash

Thompson? Did he really get his first taste of bigotry in California,

after growing up in...Arizona?

Spielberg's critics often argue that his work feels like the product of

someone who has no life experience outside of cinema. That's an idiotic

notion, one easily dispelled by watching most of his movies. And yet

with The Fabelmans Spielberg almost seems to hold his

hands up to such accusations. Sammy discovers his mother is having an

affair with a family friend (Seth Rogen) through a

Blow-Up/Blowout inspired sequence in which he notices her

interactions with her secret lover while cutting together a home movie.

Spielberg appears to be confessing that he pays more attention to the

screen than to the people around him. How could Sammy not have noticed

any of this before? After all, he was the one filming all this.

Things started to really go downhill for Spielberg when he began

collaborating with Tony Kushner, an acclaimed playwright who has

demonstrated no evidence that he understands how movies work.

Spielberg's films have become overwritten, verbose and preachy.

Kushner's clunky words often negate Spielberg's effective images. Here's

an example from The Fabelmans: After that early cinema trip, the family return to their

neighbourhood, where their house lies in darkness at the end of a street

otherwise decked out in garish Christmas lights. This is visual

storytelling, a way of showing us that the Fabelmans are the only Jewish

family on the street – it's what Spielberg has done his whole career.

But that moment doesn't work as it should because prior to it we get a

pointless piece of dialogue between Sammy and his parents that tells us

their house is the only one on the street without Christmas lights

because they're Jewish. Spielberg relies too heavily on Kushner to

elaborate on his film's themes, with characters delivering the sort of

emotional monologues that would have been thrown out of the

Dawson's Creek writer's room for being too on-the-nose.

Just in case we didn't understand the conflict Sammy feels between

following his filmmaking dreams and making his Dad proud,

Judd Hirsch turns up as a gruff family relative, arriving with a

suitcase full of exposition and laying it all out for us. Later, Sammy's

younger sister similarly sums up the family dynamic in a speech no

12-year-old ever would ever come up with. What's going on here?

Spielberg is the last filmmaker that needs to have the concept of "show,

don't tell" explained to him, so why would he allow such anti-cinematic

storytelling in his movie? Does Kushner have some damning evidence on

the director?

Kushner isn't the only detrimental collaborator here. In the past,

Spielberg would select specific cinematographers for specific projects

but ever since 1993's Schindler's List, he's stuck with Janusz Kaminski, a DoP who lights every movie as if

it's a thriller. Once again, Kaminski is an odd fit for

The Fabelmans – why does a 1960s set coming-of-age movie

look like a thriller from 2003? Spielberg's greatest collaborator is of

course the composer John Williams, but too often the director

uses Williams as a hammer. Once again Williams' music tells us how to

feel in every scene, as though Spielberg has no confidence in his own

ability to communicate ideas. But I guess if someone writes you the

themes for Jaws and Indiana Jones it's hard to let them

go.

At two and a half hours, The Fabelmans is tough going, a

lot like watching your rich neighbour's holiday footage if they had

brought a professional cinematographer on holiday. It's worth sticking

it out for a wonderful final scene involving one great filmmaker playing

another, capped off by the sort of visual gag that suggests Spielberg

still knows a thing or two about how to use a camera to provoke a

response from an audience. It sends us out on a high, but it's an ending

the film hasn't remotely earned.