Review by

Eric Hillis

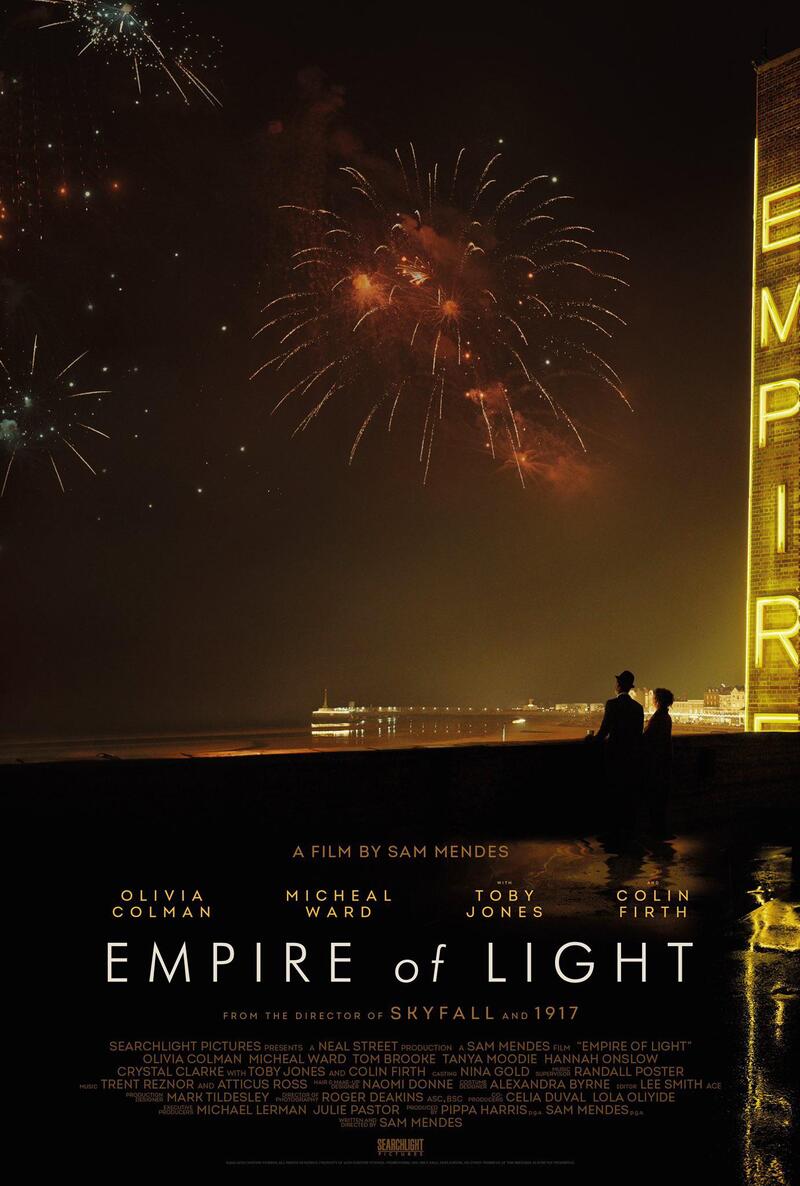

Directed by: Sam Mendes

Starring: Olivia Colman, Michael Ward, Colin Firth, Toby

Jones, Tom Brooke, Tanya Moodie, Hannah Onslow, Crystal Clarke

I recall Laura Dern recounting an anecdote from the set of

Jurassic Park, where she found herself stuck in some dark space with Steven

Spielberg while waiting for some technical snafu to be sorted. Goofing

around, Spielberg would alternate shining a flashlight onto his face

from above, exclaiming "Love story!", with lighting his face from below

and shouting "Horror movie!" Spielberg has always come across as someone

who lives, breathes and eats cinema, so it's no surprise that even his

social icebreakers revolve around filmmaking techniques. While a

talented director, Sam Mendes has never quite struck me as

someone who shares Spielberg's passion for cinema. He does of course

understand what Spielberg was getting at with his flashlight gag, that

something as simple as the placement of a light source can drastically

alter the mood of a scene, and if he doesn't, his regular

cinematographer Roger Deakins most certainly does.

That's why it's so odd when Mendes and Deakins choose to light the

troubled female protagonist of their latest collaboration,

Empire of Light, from below, thus giving her the appearance of a horror movie villain.

The scene sees Olivia Colman's mentally ill Hilary, the mousy

duty manager of a cinema on the English south coast, suffer a breakdown

while drinking wine in her flat. The light source is a lamp on a table,

which she looms over, its rays of light crawling up her agonised face,

drawing malevolence from every wrinkle and cranny. In this moment Mendes

turns Hilary, a character he's spent the rest of the movie using cheaply

as a vessel for audience sympathy, into a monster. It's as though he

doesn't really know what to do with a character like Hilary, has never

known someone like Hilary, but has gone ahead and written the character

(in crayons) regardless.

The old visual cliché of a troubled female protagonist dunking her head

below the waterline of a bath tub rears its ugly head early on, warning

us that Mendes has no ideas of his own. He may not have ever known a

woman like Hilary, but he's obviously seen movies about them. Dunking

their head underwater – that's what mad women do, right?

Like some well-meaning but annoying neighbour who insists you join them

for Christmas dinner, Mendes equates being an introvert with being

miserable. There are countless scenes of Hilary drinking alone in her

flat while listening to Joni Mitchell, which to me just seems like a

thoroughly pleasant way to spend your evening. But Hilary is a woman

without a man, so obviously she's miserable, right?

Hilary finds a man, or at least a boy, when Stephen (Michael Ward), who is seemingly the only black man in town, starts work as an usher

at the cinema. Despite being in his late teens and very handsome,

Stephen starts an unlikely affair with Hilary, shagging her in the

cinema's now-abandoned upstairs auditorium (the film is set in 1980, the

beginning of the cinema industry's worst ever decade in the UK) while

melting her heart with his Terry Molloy act of caring for a wounded

pigeon. I forgot to mention that Hilary is also shagging her boss, the

cinema's owner, who is played by Colin Firth, which will likely

erode much sympathy from the female contingent of the audience.

Stephen isn't a randomly black character, he's a prop for a half-baked

look at racism, bullied by local skinheads, taunted by customers and

eventually badly beaten. In the only glimpse we get of his home life the

TV is playing a news report about a race riot. Of course it is; he

couldn't just be watching Only Fools and Horses now could

he?

Through Hilary and Stephen's relationship we get two awful tropes – the

white saviour and the magic negro, with each serving to rescue the

other. It's a marriage of convenience. Mendes needs these characters to

come together, but he never sells it as a genuine relationship; it's

just two characters making trite points in between heavy petting

sessions. The message is that it doesn't matter if you're black or

white, and you should be nice to people. If this is all Mendes has to

say he could have just made a Hallmark Christmas movie, rather than

dragging us out to the cinema in this cold weather.

Speaking of the cinema, I'm not entirely sure why the film is set

against the backdrop of a picture palace. It could have been set in a

sausage factory or a car plant and little would have changed. Of course,

there's a schmaltzy "power of cinema" moment where Hilary watches Hal

Ashby's Being There. Unable to evoke any emotion through his own filmmaking, Mendes

resorts to borrowing the work of a real master. Similarly, when he needs

Hilary to make a point he has her recite some classic poetry rather than

rely on his own words or, Heaven forbid, images.

It's similarly unclear why the film is set in 1980, but my guess is

it's because the skinheads serve as a convenient representation of

racism, one the film's target middle class audience can frown upon

without feeling any guilt themselves. Like so many white filmmakers,

Mendes' simplistic idea of a racist is an uneducated working class thug

in bovver boots. While Stephen is harassed by the town's lower class

oiks, he's treated with affection and respect by the film's

well-educated, sensitive middle class characters like Hilary and the

cinema's projectionist (Toby Jones), who takes him under his

wing. Pass me an empty popcorn bucket.