Review by

Eric Hillis

Directed by: Oliver Hermanus

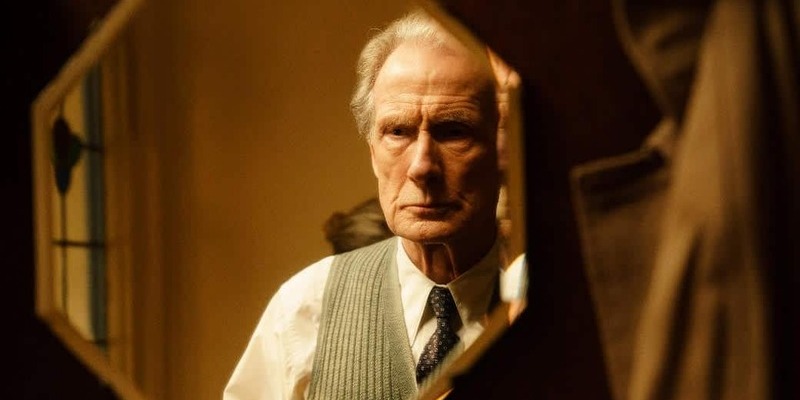

Starring: Bill Nighy, Aimee Lou Wood, Alex Sharp, Tom

Burke

In recent decades I've formed the opinion that British and Irish movies

have become so blandly mid-Atlantic in their quest for the Yankee dollar

that if British and Irish people wish to see themselves represented on

screen they're better off watching Asian movies. The characters found in the

films of Korea's Hong Sang-soo and Japan's Hirokazu Koreeda may live on the

other side of the world, but they share common traits with the British and

Irish, i.e they're an emotionally repressed lot who only open up after a few

stiff drinks or upon receiving the news that they've been struck by a

terminal illness. A couple of recent British and Irish movies have bucked

the trend. Joanna Hogg's

Souvenir

films are so distinctly English that they feel like products of the past,

while Colm Bairéad's Irish language drama

The Quiet Girl

has broken records in Ireland, finally giving Irish people the chance to see

themselves on screen as they really are.

My opinion is cemented by Living, which is English with a capital E despite being a remake of a Japanese

film, Akira Kurosawa's Ikiru. It's also tellingly adapted by a screenwriter who is both English and

Japanese, Kazuo Ishiguro, who penned the very English novel 'The

Remains of the Day'. Kurosawa's film was inspired by Tolstoy's 'The Death of

Ivan Ilyich'. If you draw a line from London through Moscow to Tokyo, you'll

find a lot of emotionally repressed men who need a few drinks to open up, or

the news that they have mere months to live. The only time my late father

displayed any outward emotion to his family was when he was preparing to

undergo life-threatening surgery. It's not that he didn't love us, it's just

that he was Irish. That's just how we are.

Living's protagonist, taciturn, some might say stuffy civil servant Mr. Williams

(Bill Nighy), receives a terminal diagnosis from his doctor and

immediately decides he needs to start living. The trouble is, he doesn't

have the faintest idea of what that entails. Disappearing from the office he

has spent his adult life slogging away in, Williams takes a trip to a

seaside town where he is taken under the wing of a beatnik played by

Tom Burke (were the movie set in the 1980s rather than the '50s

you might surmise Burke is playing the same charming cad he memorably

essayed in

The Souvenir). The two spend a night drinking, with Williams even loosening up enough

to belt out a Scottish folk tune, a hint at an otherwise unacknowledged

Presbyterian streak in the dying man. But ultimately, Williams decides he's

simply having other people's idea of fun rather than his own.

Returning to London, Williams bumps into his former underling, the young

Margaret (Aimee Lou Wood). Margaret is looking for a reference for

her new employer, so Williams takes her to a fancy tearoom while he writes a

glowing appraisal of her time serving in his office. It's simply an excuse

to spend an afternoon in the company of someone who seems to have figured

out happiness in a way he never could himself, of course. Despite Margaret's

discomfort at the idea of spending time with an older man (which isn't

personal but rather motivated by apprehension about "what people might

say"), the two form a platonic friendship, with Williams learning to live

from the younger woman.

On the surface Williams might be dismissed as a horny old man enduring an

end of life crisis, but the film quickly dispels any such notion. It's

subtly hinted that the last time Williams experienced joy was while his

mother was alive, and rather than a potential lover, he appears to view

Margaret in a maternal light. Nurses will tell you that older men on their

deathbeds will often mistake them for their mothers, and while their

interactions may occur in bustling pubs rather than a solemn ward, the

dynamic is much the same between Williams and Margaret. The relationship

between the two plays out like a "nicecore" alternative to

Phantom Thread, and it's a pleasure to spend time in their company.

Less engaging is a Capra-esque sub-plot that sees Williams embark on a

crusade to fulfil the dream of a group of working class women who wish to

have a playground erected in their neighbourhood. It feels more befitting an

American movie starring Tom Hanks rather than this otherwise very English

film, and Living's closing 15 minutes make for a somewhat clunky tribute to its

protagonist. Prior to that, the film dared to portray Williams as far from a

saint (one scene sees him engage in the sort of casual racism and sexism

that was true to the era), so it feels odd when the movie closes out with an

emotionally overwrought elegy involving a policeman coming to tears at his

recollection of Williams. Perhaps I'm being too cynical, but you'll have to

excuse me. I'm Irish. That's just how we are.

Living is on Netflix UK/ROI now.