Review by

Eric Hillis

Directed by: Giuseppe Tornatore

Featuring: Ennio Morricone, Giuseppe Tornatore, Quentin Tarantino, Clint Eastwood, Bruce Springsteen,

Hans Zimmer, Dario Argento, Bernardo Bertolucci, Oliver Stone, Quincy

Jones

If a Mount Rushmore should ever be created for film score composers,

Ennio Morricone's face would no doubt be chiselled into the

granite. In terms of working between Europe and Hollywood, in the fields

of arthouse and grindhouse, no other composer has left a legacy with

such a broad range, not to mention his musical contributions to wider

pop culture.

It's with the latter that Giuseppe Tornatore begins his look at

the discography of Morricone in what is perhaps the most insightful

portion of his doc on the composer, who passed away in 2020. Movie buffs

will know Morricone's film work inside out, but outside Italy, his work

in the field of pop music has garnered little attention. In the 1950s

Morricone transformed the sound of Italian pop music by employing the

sort of experimental arrangements and unconventional instrumentation

that would see the likes of Brian Wilson and Paul McCartney lauded the

following decade. Much of what we consider the sound of the '60s can be

traced back to Morricone's work in pop music a decade earlier.

The composer is somewhat dismissive of this period of his career,

though he's largely self-effacing throughout, a perfectionist who

suggests he never quite reached the heights he pushed himself towards.

Movie and music fans would disagree of course, and the first of those

cinematic heights came with his collaboration with Sergio Leone, an old

school friend of Morricone's. Discussing working with Leone, Morricone

is forthright regarding the amount of cross-pollination that occurs in

the field of soundtrack composition. It's now common for composers to

find themselves being asked by directors to replicate a temp track a

scene has been cut to, but this wasn't the norm in the early '60s.

Morricone tells how Leone had cut a key scene in

A Fistful of Dollars to a piece of Dimitri Tiomkin's score

for Rio Bravo and tasked Morricone with essentially coming

up with a piece of music as close to Tiomkin's as possible without

bordering on theft.

The composer is also honest about rehashing his own scores, with some

of his movie work even seeing him draw on his earlier pop tunes. His

self-effacement goes so far as to admit he felt

The Mission would have played perfectly without any music,

despite it becoming one of his most lauded scores.

Ennio runs close to three hours, but with over 400 scores

to his credit, it was never going to be a comprehensive overview of his

work. Fans of Morricone will no doubt scratch their heads at some of the

movies that fail to get so much as a mention, such as his score for John

Carpenter's The Thing, which stands out in his CV by resembling a Carpenter score more than

a Morricone score, or his distinctive donkey braying score for Don

Siegel's Two Mules for Sister Sara. Tornatore betrays a not so subtle bias towards "prestige" cinema,

with lots of time devoted to Morricone's work in lauded arthouse and

award-winning fare, but aside from his collaborations with Leone,

practically no time is devoted to Morricone's work in genre

cinema.

This is quite baffling, as in the early '70s Morricone was as key a

figure in the giallo and poliziotteschi movements as any director. When

we think of black gloved killers and crazy car chases through the

streets of Italian cities, it's Morricone's music that accompanies such

images. It's an omission akin to a John Williams doc that fails to

mention Jaws. There's something ironic about Tornatore's apparent snobbery in this

regard, as the doc heavily posits Morricone as a working class hero

pitted against the elites of the Italian music world.

While such omissions are unforgivable, Tornatore does at least explore

the films he's deemed worthy of inclusion in an interesting and

educational manner. Morricone delivers some fascinating anecdotes, like

how a filmmaker tried to steal a score he was composing for another

director, and how his father, a trumpet player, lost his musical talent,

prompting Morricone to forego adding that instrument in his work until

his father's passing.

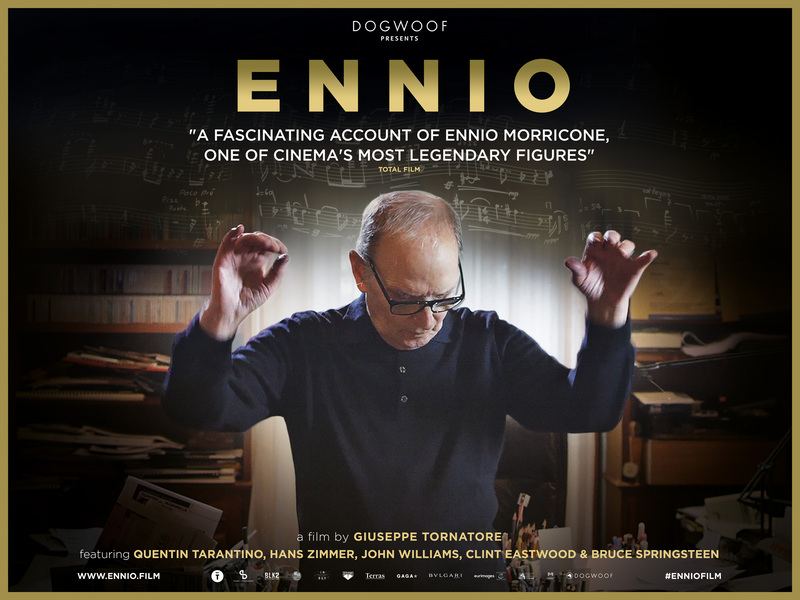

Along with a host of talking heads from the movie and music worlds of

both Europe and the US, Tornatore adds some cinematic flourishes,

skillfully editing footage of Morricone conducting an invisible

orchestra in his apartment with clips of his many live performances in

prestigious global venues. Viewers with a limited knowledge of

Morricone's work will likely end up with a notepad filled with movie

titles, but more familiar fans may find Tornatore's film insightful

while also frustrating in its film snob biases.