Review by

Benjamin Poole

Directed by: Catarina Vasconcelos

Starring: Manuel Rosa, João Móra, Ana Vasconcelos, Henrique Vasconcelos, Inês Melo

Campos, Catarina Vasconcelos

More than a mere film, Catarina Vasconcelos’

The Metamorphosis of Birds would be more accurately

described as a perfectly executed labour of love, a visual scrapbook of

memory, instances in time and abstract imagery of devastating beauty.

Nominally a biopic of Vasconcelos’ Lusitanic family, specifically her

grandfather Henrique and his wife, Triz, and the familial influence they

have upon their descendants, the film is a meditative kaleidoscope which

uses different textures, styles and witty camera trickery to express

saudade; an exclusively Portuguese expression which delineates ‘a

feeling of longing, melancholy, or nostalgia’, often for something or

somebody which is far away.

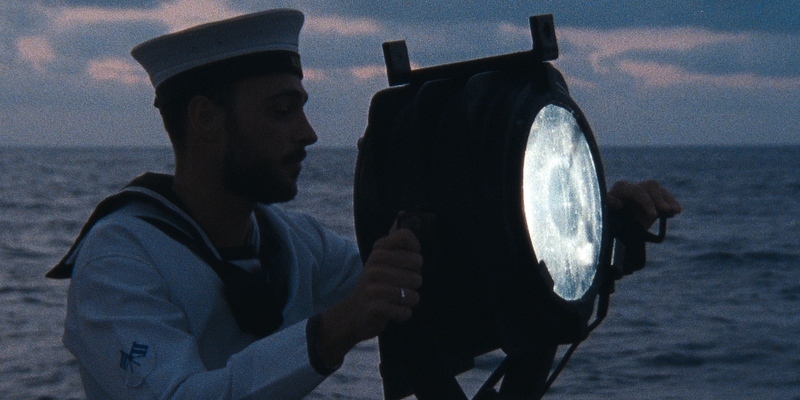

Henrique was a sailor, who was at sea for extended periods of time, and

the couple would communicate their love and longing via letters that

traversed the globe in the same way as birds in migration, eventually

finding their way to heart and home. These letters -sincere,

philosophical, devoted - form the basis of

The Metamorphosis of Birds’ narrative of thrilling visuals and uplifting emotion. Correspondingly,

the consuming sensations of Vasconcelos’ work require more than a mere

review: prepare for a hagiography.

Just as it is difficult to categorise or even describe the experience of

The Metamorphosis of Birds’ mercurial arrangement, it is also almost impossible to discuss the

sensation of watching it without lapsing wholly into superlatives. But

here goes... Using an intimate Academy ratio (mmmmmm), the film opens with

talking heads; intimate portrait shots of family members (including

Vasconcelos) which outlay the lineage and Henrique’s situation. The

various point of views blend into one another, traversing time and space:

what is one moment anticipated or feared, is in the next a bittersweet

memory. The central motif is time, and it’s inexorable passing. As

voiceovers compose the soundtrack, there is tight imagist poetry of

objects - a magnifying glass, trinkets upon shelves, a dead bird - which

are woven into the fabric of the film, inextricable from life experience.

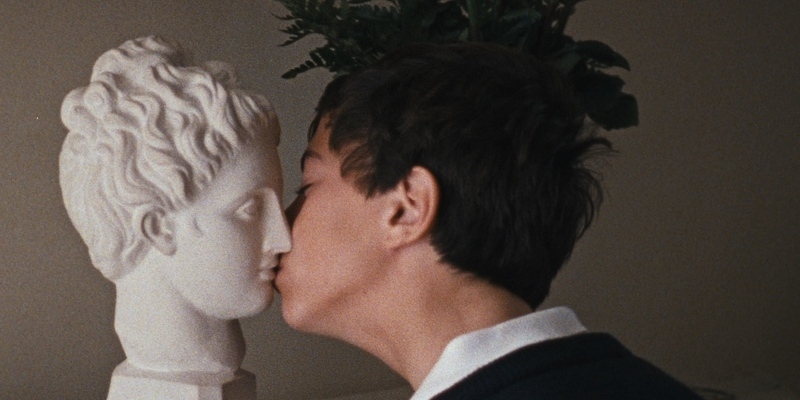

The Metamorphosis of Birds’ transcendentalism even extends to the beautiful synchronicity of Triz’s

name, which is homophonic of trees, and which, along with the delicate

creatures that alight upon their branches, provide the abiding metaphors

of Vasconcelos’ thesis.

This is the sort of film where any sequence of a minute or so contains

more riveting beauty and ravishing poetry than most other pictures manage

in a full running time (this is not a slight on cinema in general, more a

rueful observation that The Metamorphosis of Birds is such

an exceptional movie). My notes, scribbled down during hasty pauses,

runneth over - at one point a character wishes for a heart ‘as tall as the

treetops so that, from afar, I can always follow the flight of my children

who are not afraid of the wind’ (try thinking of someone you love who is

not near enough to you, and then try to read that quote aloud without

getting a lump in your throat!). At another, a character ruminates in

grief that ‘we were a still life. We observed the world as if we were

inside a painting, while outside life insisted on carrying on’. Aside from

an encapsulation of grief, this statement perhaps also pertains to

Vasconcelos herself, whose art, as expansive and explorative as it is, is

yet by its nature limited as it cannot bring people back, and only

represent events, a bittersweet artifice which necessarily involves

subjective conjecture. In the final reel we discover that Henrique’s

letters were burned as part of his dying wishes.

The Metamorphosis of Birds is on

Netflix UK/ROI now.