Review by

Benjamin Poole

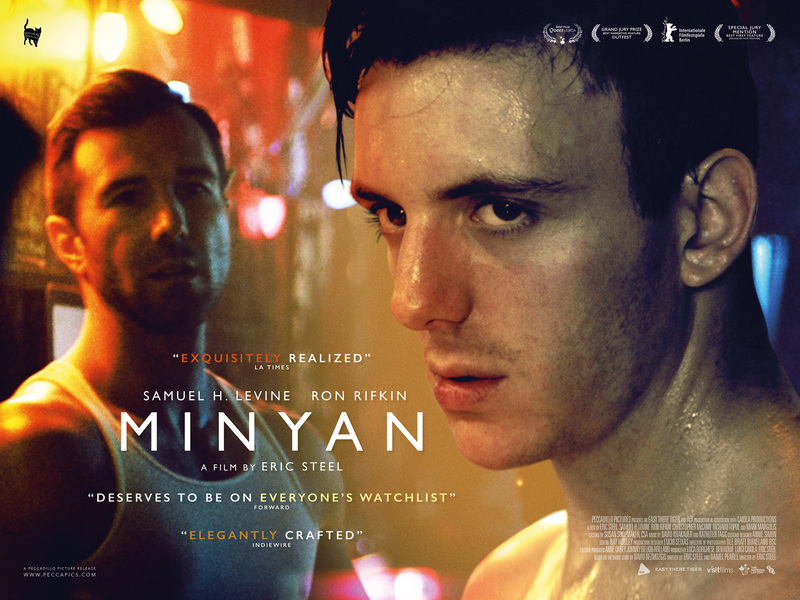

Directed by: Eric Steel

Starring: Samuel H. Levine, Ron Rifkin, Christopher McCann, Brooke Bloom, Alex

Hurt, Chris Perfetti

As part of the Ashkenazi Jewish community in 1980s Brooklyn, young David’s

(Samuel H. Levine) life is characterised by strict cultural

traditions: not only is he expected to take part in religious ceremonies

which he is unsure that he believes in, but also, as part of an outsider

class (the film suggests), competitive appearance and perceived status is

crucially important to social standing. Problem is that David is gay and

has barely come to terms with the fact himself, let alone be comfortable

enough to admit it to his family of pushy mom and abusive father - the

former attempting to marry him off to the daughter of a car salesman, his

dad smacking him about as a way of toughening him up. Oy vey!

One does tend to romanticise the mid-‘80s era of NY gay culture: the

Mineshaft club, Mapplethorpe’s photography, the mythical cool of Greenwich

village - all in the city that never sleeps. However, the reality for most

young gays at that time was far removed from the underground scene or

illicit bohemia of downtown and was perhaps closer to what David

experiences in queer documentarian Eric Steel and

David Bezmozgis’ (co-writer, of screenplay based on the short story

by Daniel Pearle) Minyan. That is, a furtive and solitary existence, exemplified by cold fear and

hot shame which eat away at the soul; as a character wistfully remarks,

"being alone is a kind of death itself."

Fortunately, David does have his grandfather Josef (Ron Rifkin),

who is similarly forsaken by the family due to his age, bemoaning that old

people are treated the same as children in their society. Duly, David

moves into the Jewish Retirement Apartment Building which Josef shares

with other older people. Part of the joy of Minyan is its

representation of old people who, to a man, have come too far and,

historically, suffered far too much to give in to further bigotry and

judgement. As David discovers, within the tenancy there are in fact a

couple of widowers who quietly live together as a couple.

It’s lovely, and the idea of David self-actualising from the example of

these dignified suitors (Christopher McCann and

Mark Margolis) is a welcome one. So many coming-out-of-age dramas

focus on youthful bravery superseding the adult status quo, and the

adolescent thrill of recognising an identity which challenges pat

orthodoxy. It’s a shame, then, that we don’t spend more time in the

retirement home, as Minyan instead opts to follow David as

he makes inroads into his newly accepted homosexuality. Once again, a

familiar gaymut is run: stealthy glances across bars, sweaty dancefloors

full of men, drunken shags. Amusingly though, Levine wanders through the

film with a benign, stupefied look on his face, as if he is the Forrest

Gump of archetypal gay experience. It’s incredible, and once you clock

this it’s impossible to ignore. Case in point is a hook up with

smouldering barman Alex Hurt. Their sex is filmed in that

objective, prolonged way in which anal is always portrayed in such films:

very po-faced, stern, mechanical (having a complete inability to take

anything seriously, let alone shagging, this sort of scene blocking always

makes me giggle anyway). After the top barman has come, the camera lingers

on David’s face, which has the sort of glazed, satisfied look of someone

who has just solved a Rubik’s cube (perhaps part of the problem is that

playing a 17 year old, Levine instead looks every year of his mid-20s irl

age...).

And then, a few moments after coitus, the hunky barman is berating David

for his ignorance regarding the endemic of young men "getting sick" across

town. Um, mate, you just had unprotected sex with this twink who is

probably still holding in your emission as you’re bollocking him? The

spectre of AIDS is another crushing phenomena that David will have to

contend with, and Minyan depicts it as such – a vague, but

insistent threat to a way of life already under undue pressure. There is,

however, no real attempt to challenge the duplicity, and possible

culpability, of the likes of the hunky barman. In fact, the bad boy’s main

crime in the film is pretending to read a book for clout, a transgression

which, when it is revealed to David, is treated like a real ‘scales from

the eyes’ moment - get real.

And so, at times, aided by its arch clarinet score,

Minyan comes across as a reassuring gay fairy-tale of

familiar tropes and minor conflicts. However, what is both warming and

refreshing in Steel’s film is the comfort, the love and the support which

David returns to within his community and religion. It is here where the

true heart of Minyan can be found, the religious-positive

themes of which are vanishingly rare. In the film’s moving final lines,

David’s rabbi explains that he is obligated to take all, "thieves,

adulterers, homosexuals," or else the titular quorum could not exist.

Minyan is in UK cinemas and on VOD

from January 7th.