Review by

Eric Hillis

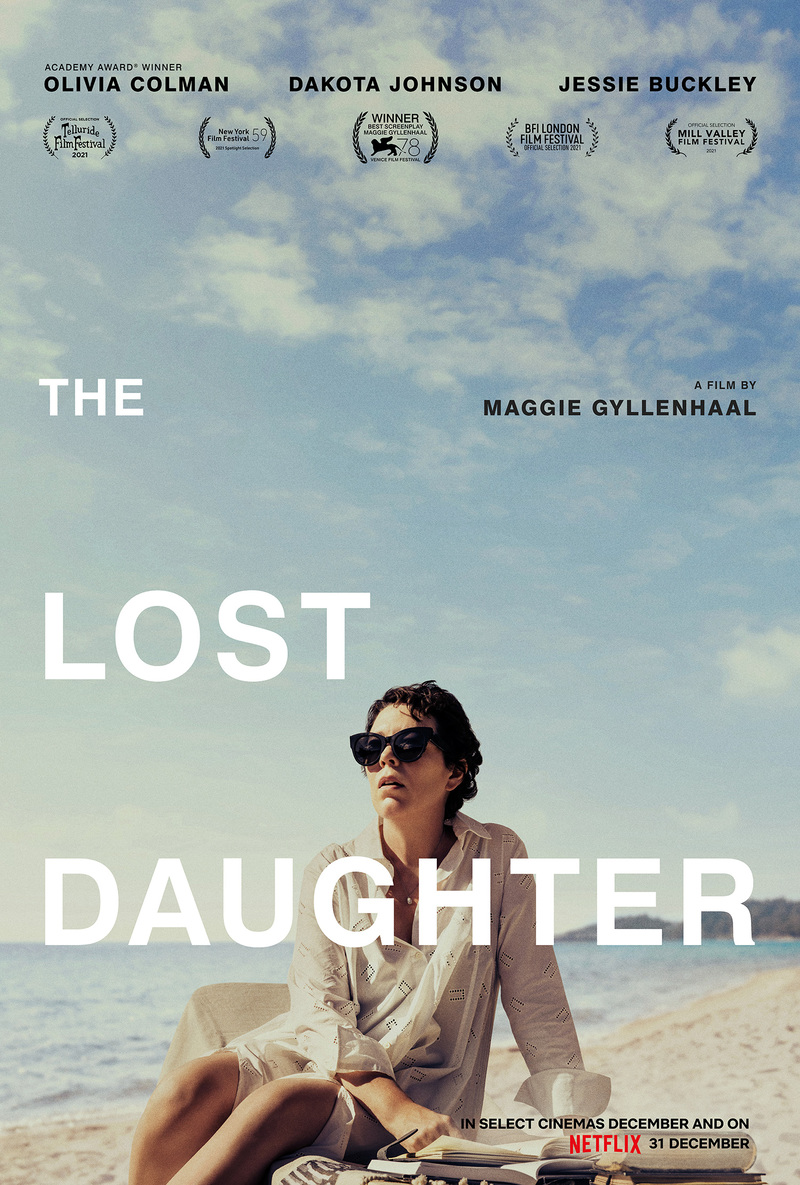

Directed by: Maggie Gyllenhaal

Starring: Olivia Colman, Jessie Buckley, Dakota Johnson,

Ed Harris, Paul Mescal, Peter Sarsgaard, Dagmara Domińczyk

One of the traits that distinguishes humans from the rest of the animal

kingdom is our spitefulness. Other creatures will inflict cruelty as a

means of survival, to keep themselves fed or to guard their territory,

but only humans cause harm to others for the sake of it. Almost all of

us will have felt this desire to cause pain to someone else at some

point, usually when we're feeling put upon and jealous that others are

escaping the misery we're experiencing. This is how genocides begin,

with a populace convinced that causing harm to one group is the cure for

their own misery. Thankfully, such human cruelty is usually worked out

of our systems during childhood, when our parents teach us that hiding

our sibling's toys out of jealousy and spite is something we need to

leave behind if we're to become stable adults.

Some of us don’t leave such feelings in childhood and carry spite into

our adult lives. With her assured feature debut as writer and director,

Maggie Gyllenhaal explores this idea in her adaptation of

Elena Ferrante's novel The Lost Daughter. The film revolves around a spiteful act, and what's daring about

Gyllenhaal's debut is that said act is carried out by the protagonist

rather than some unambiguous villain.

An arguably never better Olivia Colman is Leda Caruso, a

language professor taking a working beach break in the Mediterranean.

The location seems idyllic at first, with a beach all to herself. But

then her solace is disturbed by the arrival of an extended family of Noo

Yawkers who noisily commandeer the beach. Among them is young mother

Nina (Dakota Johnson), who holds what seems at first to be an

almost erotic fascination for Leda.

After getting on the wrong side of Nina's large family by refusing to

move to another spot on the beach, Leda gets into their good graces by

finding Nina's daughter when she vanishes from the beach. While Nina is

reunited with her daughter, the latter has lost her favourite doll.

Finding it in her beach bag, Leda decides not to return the doll to the

child but instead hides it in her apartment.

This act of cruelty and sprite propels a character study of a character

well worth studying. Leda is fascinatingly enigmatic at first as we try

to figure out just what is her motivation for hiding the doll. Does she

wish to punish the child or her mother? Is it a means to bring Nina

closer to herself, either physically or through a shared pain?

Flashbacks suggest the latter, as we see Leda as a young mother (played

by Jessie Buckley) struggling to cope with raising two young

daughters of her own. These scenes play like a reversal of the

mother-child dynamic of Lynne Ramsay's

We Need to Talk About Kevin, as here it's the mother who appears to lack empathy.

A lot of taboos have been erased at this point when it comes to women,

but one that stubbornly remains is the idea that a woman who lacks

maternal instincts is a sinister figure to be viewed with suspicion. For

a woman to admit that she has no interest in raising kids is still oddly

tantamount to admitting to eating puppies. This idea is so ingrained in

some people, especially in other women, that the audience for

The Lost Daughter is likely to be divided when it comes to

its protagonist. Some will dismiss her entirely as a woman who isn't

worthy of our sympathy, but hopefully many will recognise her as a

victim of a society that prides itself on evolving from so many animal

instincts while remaining rutted in others. If we are to shed the baser

animal instincts and evolve as a species, isn't it only naturally that

maternal instincts should follow suit?

Gyllenhaal gleefully takes on this notion, as children and family are

portrayed through the eyes of Leda as a nuisance at best, a source of

agony at worst. The women in Nina's family speak with a Catholic pride

of their children, but Nina carries her daughter not in a loving

embrace, but rather as though she's a bag of laundry she needs to drop

off on her way to the office. Not since The Specials sang 'Too Much Too

Young' has a piece of western culture shown such disdain for the

"miracle" of parenthood.

Colman is thrilling here, embodying a character that will likely make a

lot of women finally feel seen. Alone on the beach while surrounded by

people she can't relate to, she's like Jaws's Sheriff Brody – she could tell these people with their baby bumps

and never-ending families that they might not be living their best

lives, but they wouldn't listen and they certainly wouldn't understand

her point of view. As Leda's younger self, Buckley seems at first an odd

choice given her lack of physical resemblance to Colman. But by the

middle of the movie the two actresses' performances are as in sync as

the menstrual cycles of sorority sisters. I'm curious to learn the

process by which Gyllenhaal worked with the pair – did she film one

actress and show her scenes to the other, or was it simply a case that

both performers truly understood this character? A lot of women will

understand this character, but may not feel comfortable admitting

so.