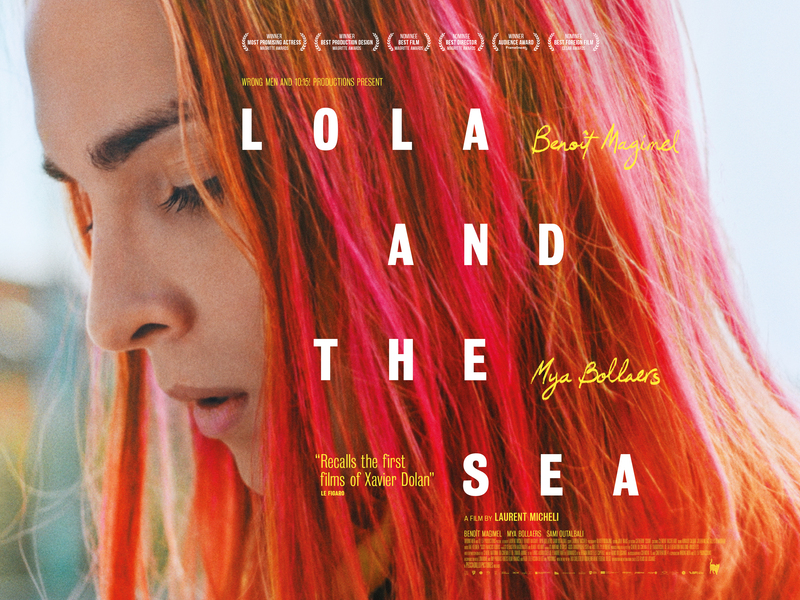

An estranged father and daughter embark on a road trip to honour the

wishes of their late wife/mother.

Review by

Benjamin Poole

Directed by: Laurent Micheli

Starring: Mya Bollaers, Benoît Magimel, Sami Outalbali

Melodrama and social realism bump heads in Lola and the Sea, the sophomore effort of Belgian born filmmaker Laurent Micheli.

Micheli’s debut, Even Lovers Get the Blues, was an LGBTQ+ themed paean to polyamory, anchored by its bisexual male

characters discovering the pleasures of passive sodomy along with the

brilliance of female breasts; its ribald art aspiring towards the

introspective eroticism of an Egon Schiele illustration (a character even

collects prints of the artist).

In Lola and the Sea, Micheli offers less adult-orientated content but a more mature

discourse on gender and sexuality. The titular Lola is a male to female

trans girl. Living in foster care, she is estranged from her family - her

dad, who is aggressively nonplussed by Lola’s biological destiny, has all

but disowned her, while her mum (who, we will find out, is more empathetic

to Lola’s situation) is in the final stages of a terminal illness.

Following a sun kissed opening of Lola skating at the park (her board,

which is from then on either strapped to her back or rolling along tarmac,

becomes a symbolic code of Lola’s transience; an all-purpose escape

route), we pick up with Lola as she learns that her mother has died.

Tragedy stimulates the narrative trigger, wherein, post the funeral and

scenes of familial conflict, Lola and her dickhead dad end up fulfilling

her mum’s wishes to deposit her ashes on a beach at the North Sea. Will

they sort out their differences and learn to accept each other’s point of

view? You’ll have to watch Lola and the Sea to find out!

Essential road movie structures aside, this is really a character driven

narrative and as such is Lola’s film. Played by startlingly watchable

actor Mya Bollaers (I use the noun in the same denotative way as I

would the word poet, as Bollaers is a trans woman), it is Lola’s simmering

angst and burgeoning self-assurance which gives

Lola and the Sea its gravity. Following a career mainly

spent before the camera, Micheli’s direction alchemises with Bollaer’s

performance to create vivid characterisation: I loved Lola’s lack of

self-pity, her anger and her impetuosity. Despite the bravado, Lola is, of

course, intensely vulnerable. She is a kid - and one who is negotiating

seismic physical change with limited support, within a society which

already ostracises her. Her immaturity manifests in bubbles of rage such

as her smashing the frontage of her old man’s store, and, in an inspired

gag, throwing pink paint over his windscreen - the dried remnants of which

stay there for the remainder of the film and the entire road journey!

Having the fortune to be born into a body I love and a sexuality I am

entirely comfortable with, films like Lola and the Sea serve

as a welcome privilege check to me and my smug ilk (which is to say that

in my happy-go-lucky bubble, it’s easy to say live and let live with Trans

issues, which in its own way is a form of ignorance: a breezily optimistic

discount of the troubled reality faced by the trans community. And while

we’re on the digression, what is the actual problem certain individuals

have with Trans people? That ‘men’ will be hanging out in ‘female’

toilets? Hahahaha - come on; there has to be an easier way for potential

wrong ‘uns to do this than gender reassignment. That ‘men’ will be

competing in ‘female’ sports? Grow up! It’s running and throwing a ball

around: who cares?).

That said, I could have done with more narrative focus on the dad:

although his hostile bigotry does thaw somewhat in the third act, perhaps

a more sympathetic portrayal would have supported

Lola and the Sea’s themes (transphobia is a sickness: a fear which requires remedy and

compassion). Instead, the rhetoric is filtered occasionally through stock

characters, such as the brassy owner of an inn the duo rock up in, and a

couple of fédérale pigs who give Lola grief, with the presence of such

archetypes giving the film an incongruous whimsy. Nonetheless this is a

solid drama, with a superb central performance. With reports that

Transphobic hate crimes are on the rise, Lola and the Sea is a film made vital by its social

context. I look forward to a future where its ideologies seem quaint and

passé, and not, as they are, urgently relevant.

Lola and the Sea is in UK cinemas

and on VOD from December 17th and in Irish cinemas from December 27th.