Review by Benjamin Poole

Directed by: Maurice Haeems

Starring: Henry Ian Cusick, Kathleen Quinlan, Erika Ervin, Jenna Harrison, Karishma Ahluwalia

Yikes! In a shady laboratory, the sickly green colour hues which match the moulded chartreuse lighting of mid ’00s torture porn, Maurice Haeems’ (writer/director) hard sci-fi morality play Chimera opens with some bloke nervously inserting his finger into a cigar cutter, and then, to the accompaniment of a gorny throbbing industrial drone, only going and chopping it clean off! It’s a sharp start, and an ensuing motif of hands is henceforth continued through the patchwork linearity of Chimera’s narrative: hands holding syringes, older digits gripping the smaller fingers of children, palms pressed in desperation against the portholes of medical holding cells. Isn’t it our hands that point to proof of scientific adaptability, the idea that opposable thumbs put us at human advantage over other unevolved creatures of the animal kingdom (those un-adapted suckers!)? It’s a question germane to Chimera, wherein, at some hazily negative point in the near future, beleaguered scientist Quint (Henry Ian Cusick) struggles to find a cure for the degenerative disease which his little kids have contracted. Immortality vs immorality? The implication of Quint’s children means that all ethical questions are down the sluice sink. And so cloned dogs (no!), pigs and, horrifically, an antiseptic library of human embryos are farmed by Quint in the hope of finding a solution as time ticks down.

Chimera is itself a bit of a, well, chimera, with genre tropes and conventions inexpertly patched together to create a hybrid narrative. Kathleen Quinlan takes a villain role, bankrolling Quint’s research but also holding him to ransom in order to repair her own son, who has mutated into a fully-grown monster. There’s the poignancy of Quint’s personal drama: the film cuts back, forth and sideways as it shows family Quint during the best of times and the worst. Quint’s lab partner is a voice piece for the sort of cod anti-stem cell research arguments you get in tabloid newspapers (or is she…? Could this femme fatale be playing a duplicitous long game?). It also turns out that Quint’s 10 year old son is an unlikely admirer of the plays of Samuel Beckett, quite gratuitously comparing himself and his doomed sister to Vladimir and Estragon at one point.

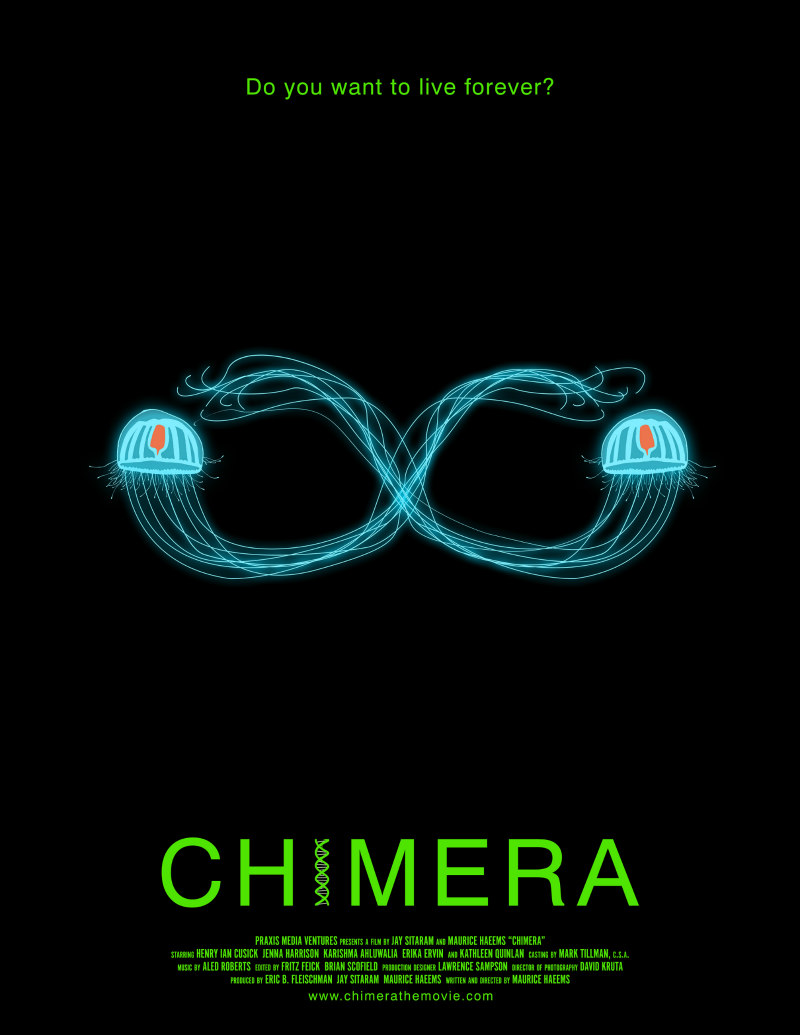

It is all dreadfully confusing. Full disclosure: the plot details outlined above are a sincere recount of my personal understanding of the film, and they are a guess at best (an educated guess: I have 10 GCSEs, after all). From a story point of view the bewildering plot turns and obtuse montage of Chimera turn out to be needlessly byzantine, as the final act swerves into a narrative twist which throws preceding events into further relief. The individual ideas of this ambitious science fiction are in themselves intriguing; Quint’s investigations centre initially upon a certain breed of immortal jellyfish, and the theory of biodiversity being located within the original, oceanic source of our evolution is pleasingly neat, but before this concept can be fully explored, we jump forward/back to something like a dog being frozen or Quint’s fragrant wife looking a bit dewy and winsome, the convoluted structure doing the film no favours.

By the time the gruesome imagery of the film’s denouement occurs (a genuinely distressing sequence which ups the gamut of the opening’s finger chop), perhaps it is possible to splice together the disparate DNA of Chimera’s plot into a hodgepodge whole. But, to paraphrase the denizen of another clone-monster-run-amok flick, here it’s not a case of whether or not you could or should, but whether you can actually be bothered to.

Chimera will screen at Portugal's Fantasporto film festival on February 24th.