10 of the most memorable movies to take home the top prize at the world's most prestigious film festival.

Words by John Bennett

The dizzying whirlwind of international cinematic visions that make up the heart and soul of the Cannes Film Festival will soon tear through the mid-sized beach town on the French Riviera. Though many of the 100+ films are bound to be exceptional, only one from the Official Selection’s competition will take home the coveted Palme d’Or* - an award that can perhaps boast a better track-record for quality than any other throughout all of cinema’s self-congratulating apparatuses. Here are 10 Palme d’Or winners that have withstood the test of time - films that feel fresh, adventurous, and relevant even today.

The Wages of Fear, Dir. Henri-Georges Cluzot, 1953

One of the last winners of the Grand Prix before the Palme d’Or was established, The Wages of Fear is an incomparable blend of entertainment and social commentary. Four truck drivers (the most notable of which was French actor/singer Yves Montand) are hired by a slimy oil company to perform the dangerous task of driving two trucks of nitroglycerin across treacherous Mexican terrain. Needless to say, the film drips with tension, and each thrilling moment reminds us of the callousness of certain large anonymous companies. The indictment of capitalism mixed with the superbly exciting narrative made The Wages of Fear a perfect post-war winner of Cannes’ highest honour.

The Cranes Are Flying, Dir Mikhail Kalatozov, 1957

If The Wages of Fear may have won because it showed European post-war anxiety, The Cranes Are Flying may have triumphed because of its romantic yet traumatic remembrance of the war. Underrated director Mikhail Kalatozov’s masterpiece follows Veronika, a young woman who tries to navigate a chaotic, war torn Russia, all while trying to discover the fate of her soldier boyfriend. Though this film doesn’t shy away from the horrors of war, its lyrical style speaks volumes about the worth and the irony of hope in the midst of hopelessness. Kalatozov was a supreme stylist, so his blending of atrocity and beauty into one forceful poem may have been what earned him the Palme.

La Dolce Vita, Dir. Federico Fellini, 1960

In 1960, the film festival awarded its top prize to Fellini’s iconic La Dolce Vita, a film that helped propel European art cinema into its thoroughly modernist '60s period. Lacking much discernable plot, this epic of ennui follows Marcello (Marcello Mastroianni, giving what was probably the best performance of his career), a gossip reporter who hangs around a glamorous but vapid high society in Rome. As Marcello drifts from party to party, Fellini gives us hints as to what the prices of empty living might be. Nevertheless, glam devoid of all meaning is still glam, and Fellini’s iconic film sauntered off with the film world’s most iconic prize.

Blowup, Dir. Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966

The similarities between Antonioni’s Blowup and La Dolce Vita are palpable; and maybe that’s why Antonioni’s #2 masterpiece (after 1960’s L’Avventura) garnered the same honour as Fellini’s did six years earlier. In what seems like a post-modern splintering of La Dolce Vita’s ideas, photographer Thomas (a scowling David Hemmings) drifts through London’s swinging '60s nightlife scene. Only things aren’t as swinging as they seem: the partygoers and models act almost like zombies, strange mimes run amok, and something as serious and mysterious as a possible murder will be passed by with unnerving indifference. Even so, I’ll reiterate - even if empty, glam is glam, which made Blowup a prime candidate for winning le grand prix.

M*A*S*H, Dir. Robert Altman, 1970

Scorning European art-house in favor of American political satire, Robert Altman’s breakthrough film, M*A*S*H enjoyed Cannes accolades at the opening of a politically turbulent decade. Well before M*A*S*H came to television screens, Hawkeye (Donald Sutherland) and Trapper (Elliott Gould) served as the doctors/clowns at the center of Altman’s ensemble vision of a Korean War medical unit. The film in which Altman first showcased his trademark style, one full of overlapping dialogue and wandering camerawork, M*A*S*H seemed to use its Korean setting as a front: Vietnam appeared to be the war that was actually being lampooned. And seeing as the Vietnam War was universally despised by the art community, it stands to reason that a critical American film received Cannes’ top award.

Farewell my Concubine, Dir. Chen Kaige, 1993

Japanese cinema had been an art-house staple since the '50s, but it took other Asiatic cinemas a bit longer to gain recognition. Chinese cinema was recognised in a big way when Chen Kaige’s epic Farewell My Concubine won the Palme d’Or in the early '90s. A film of great sweep, Farewell My Concubine follows Dieyi (Leslie Cheung) and Xiaolou (Zhang Fengyi) over a period of 50 years. The two gain prominence in the Peking opera scene, and soon major events from Chinese history and their own stormy friendship become as intense as the dramatic operas they perform. Kaige’s film is as epic as a David Lean and as sleekly produced as a Spielberg, but its dedication to exploring Chinese culture, art’s relationship to life, and a friendship of a thousand nuances made this fifth Generation epic a perfect candidate for the Palme.

Secrets & Lies, Dir. Mike Leigh, 1996

Of the films on this list, Mike Leigh’s Secrets & Lies might have the most straightforward narrative and style, but that doesn’t preclude it from having been worthy of Cannes’ highest honour. In what is probably Leigh’s best film, Hortense (Marianne Jean-Baptiste), a successful optometrist who was adopted as a child, decides to try to discover the identity of her birth mother. That woman is the rough-around-the-edges Cynthia (Brenda Blethyn), who, along with her photographer brother (Timothy Spall) and her surly daughter (Claire Rushbrook) come to terms with the dramatic change that Hortense’s presence brings to their lives. Though it reads like a melodrama, Leigh’s film is patient and slowly ensnares you in the complex emotional lives of its characters. A different kind of Cannes winner, but a must-watch all the same.

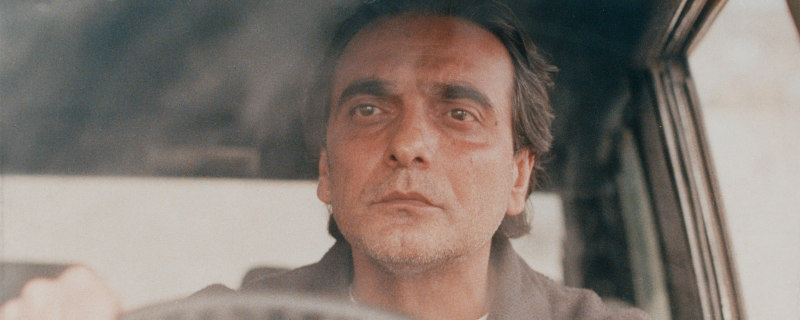

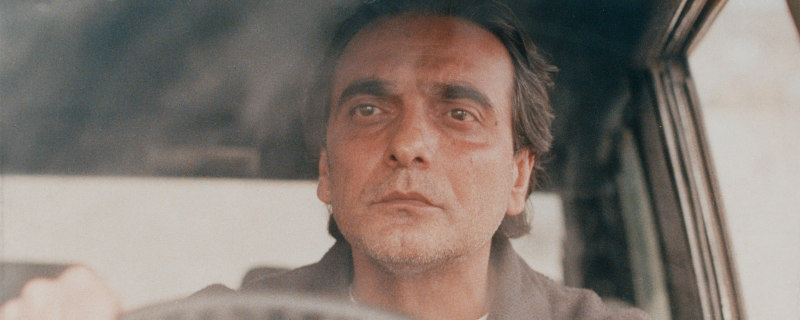

Taste of Cherry, Dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 1997

The Palme d’Or returned to its art-house bent the year following Secrets & Lies in order to laud Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry. In this death-haunted work, an Iranian man (Homayon Ershadi) plans on committing suicide. He roams around the environs of Tehran in order to find someone who will be willing to bury him after the fact. Kiarostami uses this story not as a platform for moralising, but rather as a deeply ambiguous way to represent life in a complicated country. Recognising a new generation of Iranian directors (see Panahi and Makhmalbaf), the Palme rightfully went to a film that represented a larger blossoming movement of a national cinema interested in visual poetry and complex political discourse.

4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, Dir. Cristian Mungiu, 2007

In recent history, Cannes has rewarded films that exemplify national cinematic movements. Farewell My Concubine was an epic centerpiece of fifth Generation Chinese cinema, just as Taste of Cherry was one of the most poetic entries of New Iranian cinema. In 2007, the top prize went to Cristian Mungiu’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, an exceptional, brooding film that stood out among the New Romanian Cinema movement. In Mungiu’s version of communist-controlled Romania, a young woman named Gabita (Laura Vasiliu) needs to have an abortion, which under communist rule was politically and bodily dangerous to organise and perform. Her college friend, Otilia (Annamaria Marinca), takes great risks to help her. Mungiu’s sinister depiction of Gabita and Otilia’s efforts brilliantly demonstrated the needlessly traumatic consequences of draconian laws in very recent history, and the attention that the Palme d’Or drew to the film reminds us of how many places those laws are still in effect.

Blue is the Warmest Colour, Dir. Abdellatif Kechiche, 2013

Seeing as Cannes is, en fin du compte, a French festival, we’ll finish with Blue is the Warmest Colour, an intense anatomy of a relationship from director Abdellatif Kechiche. In an unprecedented move on the part of the festival, the Palme d’Or was awarded not only to Kechiche, but also to leading actresses Lea Seydoux and Adele Exarchopoulos. Adele (Exarchopoulos), a young girl who seems dissatisfied with her high school’s social and romantic scene, slowly begins a romantic relationship with the slightly older Emma (Seydoux). The film traces their relationship from beginning to end: from its hesitant beginnings, passionate high period, devastating cooling, and ultimate break. In a time when it seems hard to shock audiences, Blue Is the Warmest Colour's awards at Cannes drew attention to just how controversial the film was in its unapologetic depiction of explicit sex scenes. Some (including the leading ladies) saw these scenes as superfluous and lecherous, while others saw them as natural moments in the depiction of a relationship. Either way, it gave viewers something to think and talk about, and any film that arouses a telling and smart debate is, in my eyes, worthy of the premier prize of the world’s premier film festival.

*Between the festival’s inception in 1939 and 1954, the award was known as the Grand Prix du Festival International du Film. The prize had the same name between the years 1964 and 1974. Technically, The Wages of Fear, Blowup, and M*A*S*H all won the Grand Prix, but for all intents and purposes, the prizes are synonymous.