Review by

Eric Hillis

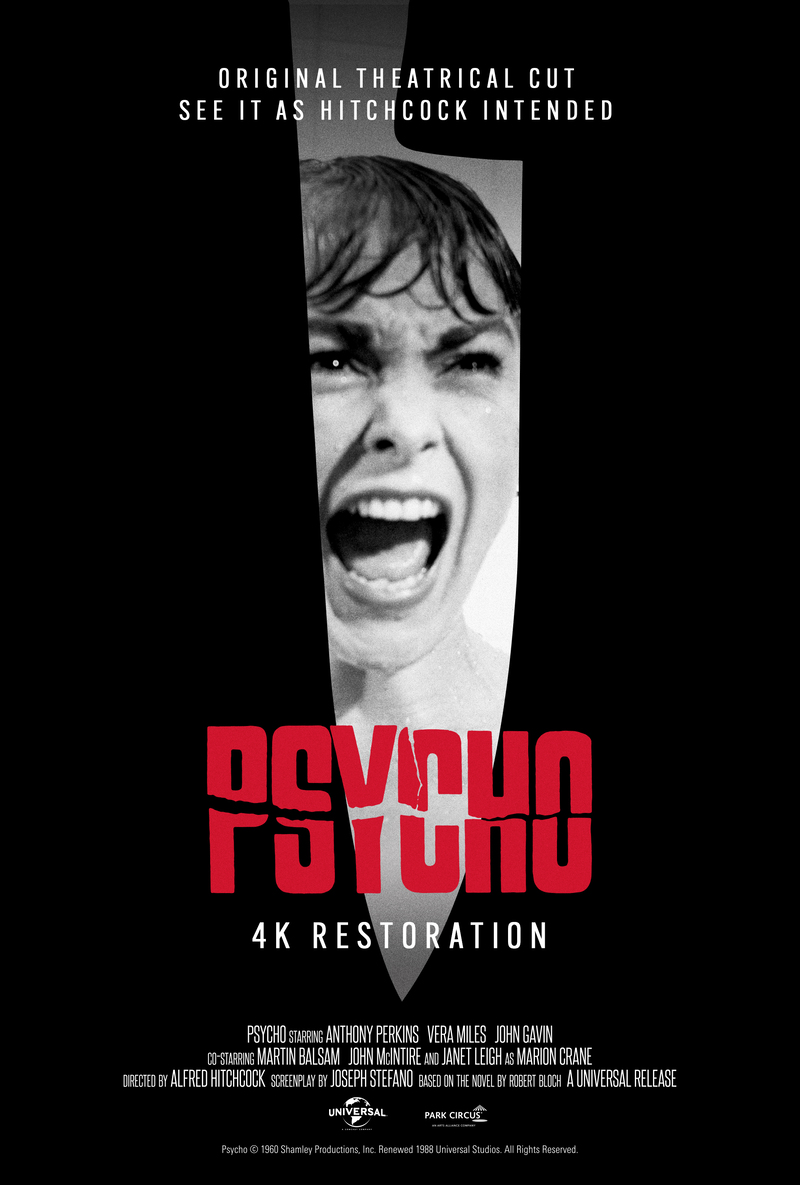

Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock

Starring: Janet Leigh, Anthony Perkins, Vera Miles, John Gavin, Martin Balsam, John McIntire, Vaughn Taylor

Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock

Starring: Janet Leigh, Anthony Perkins, Vera Miles, John Gavin, Martin Balsam, John McIntire, Vaughn Taylor

Arizona secretary Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) wants nothing more than

to wed her lover, Sam Loomis (John Gavin), but the pair are dead

broke. When Marion's real estate boss (Vaughn Taylor) entrusts her

with a client's $40,000, the young woman seizes the opportunity and leaves

Phoenix, headed for California and the prospect of a new, financially secure

life with her lover. That night she pulls into a motel run by a charming

young man, Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), and following an

insightful conversation with him, Marion decides she will return the money

to Phoenix first thing in the morning. Before retiring to bed, however, she

decides to take a shower...

In 1960, Hollywood was in trouble. Television sets had finally penetrated

the American home to an almost comprehensive degree. To combat the threat of

small screen entertainment, Hollywood had gone big, using gimmicks like 3D

and

various widescreen formats

to entice audiences away from the goggle box and back into theatres. Many of

these mega-budget movies had been massive flops, placing studios in serious

financial trouble. This meant filmmakers, even those as respected as

Alfred Hitchcock, were forced to reign in their creative ideas.

Studios wanted safe bets, not experimentation. Hitchcock, however, had spent

his entire career experimenting with cinema, and wasn't about to stop

now.

The movie moguls of Tinseltown were focussed on giving audiences something they couldn't get on TV - spectacle. But there were two other things you couldn't see on TV in 1960 - sex and violence! Using these two elements, a new wave of low budget filmmakers like Roger Corman and William Castle were raking it in, enticing viewers back into theatres, or at least drive-ins, with the dual promise of titillation and terror. It was a promise largely unfulfilled, despite the lavish claims of the films' extravagantly lurid posters, as this was, after all, still the era of the Hays Code. But the sight of bikini babes ravished by crab monsters wasn't something you were going to see on Father Knows Best and audiences flocked in their droves to exploitation movies, at the expense of many a lavish, star-studded spectacle.

Hitchcock was fascinated by these low-budget movies and wondered, rather

egotistically, what it would be like if a great filmmaker like himself were

to venture into the world of exploitation films. When Robert Bloch's

novel Psycho landed on his desk, Hitchcock immediately decided this was to be his

next movie. Loosely inspired by the exploits of Wisconsin murderer Ed Gein

(later to inspire '70s grindhouse favorites The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Deranged), Bloch's novel contained all the sleazy elements Hitchcock was after. The

execs at Paramount, where Hitchcock was currently under contract, were

repulsed by the idea and refused to fund it, leading the director to take

the gamble of self-financing the film, shooting on Universal's stages with

his Alfred Hitchcock Presents TV crew. It's a gamble that paid

off massively when the film earned $60 million at the box office from a

budget of $800,000, leaving those Paramount suits looking decidedly

foolish.

If Vertigo is the critical darling of Hitchcock's oeuvre, Psycho is certainly the people's favourite. Ask any casual film-goer to name a Hitchcock film and this is the reply you'll most likely receive. Like many Hitchcock fans, I find its status somewhat irksome, as its popularity overshadows at least a dozen less acknowledged yet superior movies from the director's catalog. While time has been kind to Psycho and modern critics now appreciate it for the great thriller it is, the reaction on its original release was vehement, with many critics confessing to walking out before the film's climax. "It is incumbent on us to inspect the real horrors of our time, but we don't have to traffic with Hitchcock's giggling obscenities," Robert Hatch wrote in his review for The Nation, while back in Hitchcock's homeland, Observer critic CA Lejeune wrote "I couldn't give away the ending if I wanted to, for the simple reason that I grew so sick and tired of the whole beastly business that I didn't stop to see it." Lejeune, who had been similarly repelled by Michael Powell's Peeping Tom, was so adversely affected by Psycho that she quit her job after writing her review.

It would seem the atrocities critics believed they graphically witnessed on

screen had been enough to turn them off Hitchcock's thriller. But this, of

course, was the director's great trick. Though the film contains some brutal

knife murders, we never actually see anyone physically stabbed. The famous

shower scene uses editing in such a rapid manner that we feel the violence

without actually seeing it. We're never explicitly shown a knife cutting

flesh but the physical cutting of the small strips of film, some as short as

three frames, has an incredible psychological effect on us. Those of us too

young to have experienced the film on its 1960 release can only wonder how

audiences must have reacted to this scene. Previously, murders generally

occurred off screen, so to witness a scene of violence handled with the same

level of craftsmanship (the scene took a week to shoot) as a lavish MGM

dance number must have been quite something. While audiences never actually

witnessed any explicit violence, had they looked carefully they would have

seen the exposed nipple of Leigh's body double, Playboy cover girl

Marli Renfro, a cheeky middle finger to the unobservant censors from

Hitchcock.

It's rare for Hitchcock to be outshone, or even equalled, by the work of

his collaborators, but the contributions of Perkins and composer Bernard Herrmann

are just as much a part of Psycho's success as his direction. Perkins' turn as Norman Bates is arguably

the best performance by any male actor in a Hitchcock movie, rivalled only

by Jimmy Stewart's Scottie Ferguson in Vertigo or Joseph Cotten's Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt. As a modern audience, the film's twist is ingrained in our cultural

awareness alongside those of Planet of the Apes and The Crying Game (though the latter's revelation had previously been pulled off in

the low budget slasher Sleepaway Camp). This allows us to appreciate Perkins' performance all the more as even

though we know what he's responsible for, we can't help but empathise with

him. Who among us doesn't will Marion's incriminating car into the swamp

when it becomes momentarily stuck in the mud on Norman's attempt to

dispose of the evidence of "Mother's" crime?

Along with Hitchcock and Perkins, Herrmann's work on Psycho is responsible for elevating its status but it could have been very different had the composer obeyed his director's initial request for a jazz-influenced score. The reduced budget meant Herrmann couldn't afford the full symphonic orchestra he was used to working with and instead solely employed a string section. The result is arguably the most identifiable score in cinema history, and certainly the most imitated. For decades, until the emergence of the synthesizer, composers ripped off Herrmann's score when working on horror movies. Listen to Pino Donaggio's score for Brian De Palma's Carrie or Harry Robertson's work on Hammer's The Vampire Lovers and it's easy to hear where they took their cues from. For the 1985 horror comedy, Re-Animator, composer Richard Band took Herrmann's score and altered it in minuscule detail, turning it into a more comedic sounding score, a technique made popular by the many musical homages of the animated TV hit The Simpsons. Of course, it's Herrmann's accompanying staccato string 'stabs' for the shower scene that are most well known, but the more low key incidental themes are equally chilling, making effective use of low end bass to create a disturbing ambience.

Credit for Psycho's iconic status must also go to production designer

Robert Clatworthy and art director Joseph Hurley, the men

responsible for designing the Bates' house. The pair took Edward Hopper's

1925 painting, 'House by the Railroad', as inspiration and created the

creepiest building ever seen on screen. To this day it's a highlight of the

Universal Studios tour.

The shower scene. The haunting score. Perkins' unforgettable performance.

Psycho may not be Hitchcock's greatest achievement, but it's arguably his

most iconic and certainly his most influential work.

Psycho is in UK/ROI cinemas from

May 27th.