Review by

Eric Hillis

Directed by: Mia Hansen-Løve

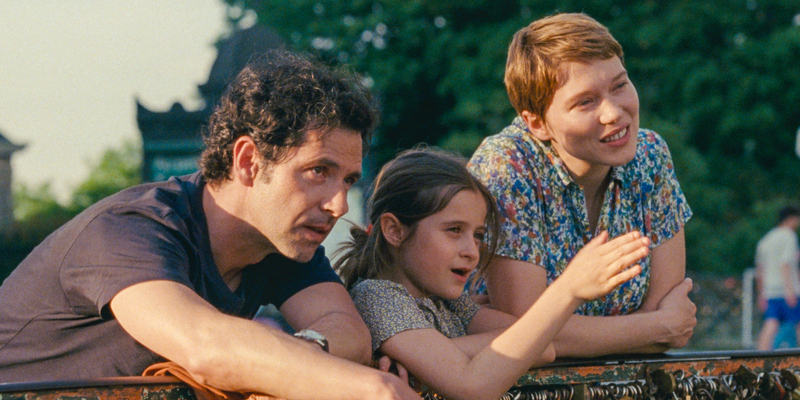

Starring: Léa Seydoux, Melvil Poupaud, Pascal Greggory, Nicole Garcia, Camille Leban Martins

There's a brutally honest moment of human fragility near the end of

writer/director Mia Hansen-Løve's One Fine Morning. After saying goodbye to her senile and sightless father on a visit to

the depressingly utilitarian care home where he now resides, our

protagonist, Léa Seydoux's Sandra, is waiting for an elevator

when her old man, Pascal Greggory's Georg, wanders out of his

room and down the corridor towards her, calling out the name of his

lover, Leila (Fejria Deliba). Sandra could be a dutiful daughter

and walk her father back to his room, going through the process of

bidding him farewell all over again, but instead she pretends not to

notice him and enters the lift.

Out of context it could be viewed as a scene of immense cruelty, but

we've spent so much time with Sandra by that point that we fully

understand her actions. Sometimes saying goodbye is so painful that you

simply can't repeat it. This is especially so in the case of an elderly

parent whose time on this Earth is, you suspect, limited, as is the case

with Georg, once a lively professor, now a decaying shell housing a

rapidly disappearing soul.

With her latest drama, Hansen-Løve explores a truth that's rarely been

addressed in cinema before. It's the idea that we begin the grieving

process not after our loved ones pass away, but often well before their

light finally burns out. That's particularly the case if you have a

parent suffering from a chronic condition. The person who raised you

begins to disappear long before they actually pass away, and one of the

hardest things can be not knowing how long they have left, leaving a

question mark at the end of every goodbye.

Just to make matters worse for herself, Sandra, a widowed mother of a

young girl, Linn (Camille Leban Martins), is having an affair

with a married man, Clément (Melvil Poupaud). Like so many in

such a scenario, he claims that he'll leave his wife for Sandra but

never seems to be able to pull the trigger. This leaves Sandra wondering

if he'll ever return each time she bids him goodbye. It's a mirror of

the situation with her father. The two men Sandra loves could vanish

from her life at any moment.

Seydoux tangibly conveys the feelings of a woman who needs to be strong

for both her father and her daughter, who doesn't have the luxury of

being able to curl up in bed for a few hours and cry her eyes out. There

are moments when she breaks down in public, disrupting a conference

where she's working as a translator and fleeing from one of her father's

former students, whose praise for him is too much for Sandra to bear.

But mostly she's forced to hold herself together. There's a palpable

sadness in Seydoux's eyes throughout, even in Sandra's happier moments

(there's a truly joyous Christmas scene that will move even the most

rigid of atheists), because they're so loaded with uncertainty. Having

lost her husband, she's haunted by the thought of further

abandonment.

I have to confess I've struggled to relate to much of Hansen-Løve's

work, save for

Eden, because like the protagonist of that movie I was once a DJ who had to

eventually quit doing the thing that brought me the most joy. Much of

this is down to the very middle class milieu her characters reside in.

You're not going to see Hansen-Løve make a movie about a car plant

worker who comes home every evening, cracks open a beer, puts his feet

up in front of the telly and promptly falls asleep. Her protagonists are

usually glamorous women whose job is to translate some Austrian

philosopher's work into French, and they always seem to live in Parisian

apartments that should be well out of their pay-grade. But with

One Fine Morning she's made a movie on a universal theme.

Whether your job is to affix rivets to car doors or restore archaic

texts, whether you live in Neuilly-sur-Seine or the banlieues, love and

death will get you in the end, or perhaps as

One Fine Morning suggests, even sooner.