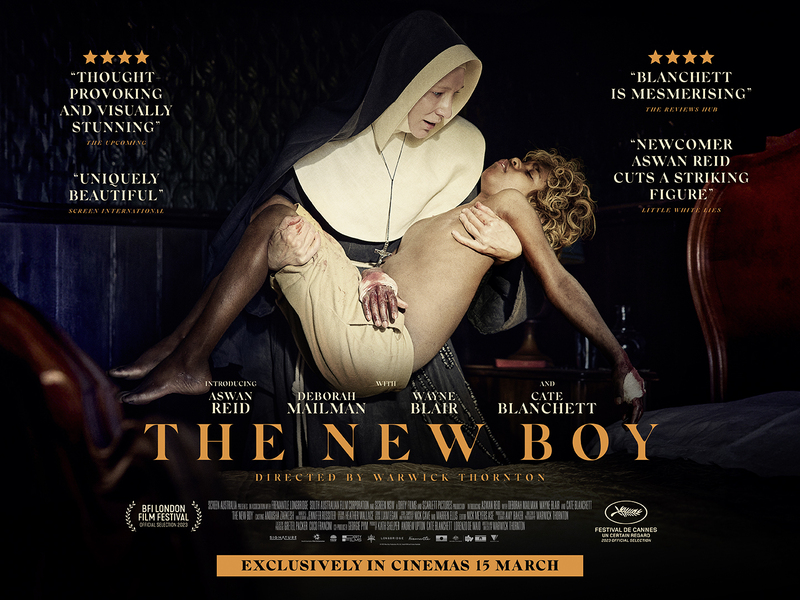

When a young boy in her care begins to display supernatural powers, a nun

is forced to question her allegiance to her church.

Review by

Eric Hillis

Directed by: Warwick Thornton

Starring: Cate Blanchett, Aswan Reid, Deborah Mailman, Wayne Blair

Indigenous Australian writer/director Warwick Thornton draws on his

own childhood experience of being raised in a Catholic boarding school for

The New Boy. His own story is highly embellished with magic realism, making for a film

that plays like a reversal of the dynamic of that old Hayley Mills Sunday

afternoon staple Whistle Down the Wind. In that film a child comes to believe a fugitive is Jesus. Here it's an

adult who is forced to reckon with the idea that a child may be the new

Messiah.

In a stylish slo-mo opening we see a young aboriginal boy (Aswan Reid) flee from a white policeman, only to be knocked out by a boomerang hurled

by the cop's indigenous accomplice, an early sign of the complicated racial

dynamics Thornton is set to explore. The boy is brought to a remote

monastery where indigenous boys are indoctrinated into Christianity as part

of Australia's "breed out the black" campaign. There he finds himself in the

care of Sister Eileen (Cate Blanchett), who has taken over the

monastery following the death of Don Peter, the priest who was previously in

charge. Abetted by an indigenous nun who likes to be called "Sister Mum" (Deborah Mailman), Eileen has kept Don Peter's passing a secret, even from the boys, who

believe he is confined to bed with a sickness.

It's customary for Eileen to give each of the new boys a Christian name,

but Eileen decides to hold off and simply call the new boy "New Boy" for

now. She seems to see something special in New Boy, giving him the sort of

leeway she has denied the other boys in her care. New Boy is indeed special.

He possesses supernatural powers, and when he's alone he likes to unleash a

small orb of light, the sort that might house Tinkerbell. It's one of

several allusions to JM Barrie's most famous work, along with the absent Don

Peter and the children in Eileen's care being referred to as "lost

boys."

New Boy gets to demonstrate his powers when one of the boys is bitten by a

deadly snake, miraculously healing the child. When a statue of Christ on the

cross arrives, New Boy becomes strangely obsessed and seems to communicate

with the figure, causing Eileen to question everything her religion has led

her to believe about the Messiah. Could Christ really be returning in the

form of this little aboriginal boy?

In attempting to mix spirituality with Spielbergian wonder, Thornton's film

often comes off as misjudged and dare I say, a little silly at times. The

movie works best when it's ambiguous, but any ambiguity is dismissed early

on once New Boy's powers are revealed. When the statue of Christ starts

blinking it's unclear whether the image is to be taken literally or as a

child's delusion, but either way it's an incredibly cheesy moment that

breaks any spell the film might have you under by that point. There are

other histrionic moments that are equally miscalculated: when Eileen spreads

herself atop the grave of Don Peter, it unfortunately recalls a similarly

over the top moment in

Saltburn.

Blanchett's performance might be the low point of her career. She's bad

here in the way that only great actresses can be bad, dialled up to 11 like

one of those awful late career Meryl Streep performances. You get the sense

she doesn't really understand Sister Eileen, so it's difficult for the

audience to get a handle on the character. Blanchett is acted off the screen

by young Reid, whose wordless performance is beguiling in all the right

ways.

By its nature The New Boy is critical of colonialism, but

Thornton avoids the sort of broad critique you would likely get from a

guilt-ridden white filmmaker. We're left to reason ourselves that abducting

children and indoctrinating them into another culture is despicable, but

nobody in the film expresses this sentiment. Far from the cliché of the

tyrannical nun, Sister Eileen is a genuinely decent person who is doing what

she believes is best for the boys. We assume Sister Mum was once abducted

herself, but Thornton allows Mailman to express any suppressed heartache

through subtle facial expressions. Perhaps the most interesting character is

George (The Sapphires' director Wayne Blair), the monastery's aboriginal caretaker. He

seems particularly unsettled by the presence of New Boy. "Don't bugger this

up for me," he warns the kid, giving the impression that he's spent his life

trying to make white people forget who he is and where he comes from, and is

worried New Boy's untamed nature will cast him once more into an unwanted

spotlight.

The subtleties of Sister Mum and George's relationship with their surrounds

stand in stark contrast with the film's more outre expressions of

spirituality however. Ultimately the film's success or failure depends on

whether you buy into its depiction of the supernatural or not. I like to

think of myself as an atheist in reality but a fundamentalist in the cinema

- i.e. I'm willing to believe anything for the running time of a movie if

the filmmaker can make it convincing - but Thornton's theatrics never

penetrated my layer of skepticism.