Review by

Eric Hillis

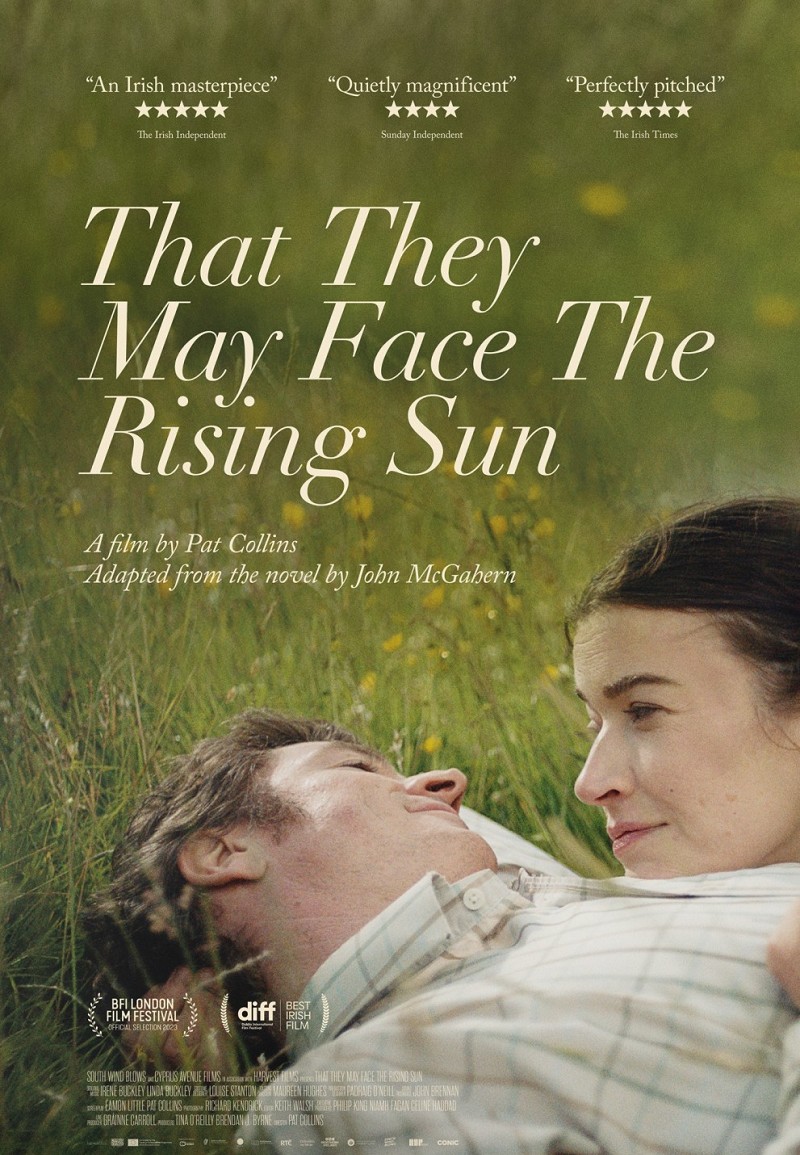

Directed by: Pat Collins

Starring: Barry Ward, Anna Bederke, Philip Dolan, Lalor Roddy,

Sean McGinley, Brendan Conroy

"There's not much drama, more day to day stuff."

That's how the central figure of

That They May Face the Rising Sun attempts to describe the

book he's currently writing. It's a statement that could sum up director

Pat Collins' film, an adaptation of the final novel of

John McGahern. This is a film almost completely devoid of the

sort of elements screenwriting gurus insist are essential. There's

practically no conflict and the biggest drama comes when two old men

reenact a scene from The Playboy of the Western World. It's about the

simple joy of living day to day, of friends drifting in and out of your

life and your kitchen, of being content with your lot. It's

beautiful.

Set in pre-Celtic Tiger rural Ireland, the film will likely draw

comparisons with recent Irish films like

The Quiet Girl

and

Lakelands, but the contemporary film it has most in common with is Jim

Jarmusch's

Paterson. Like that film it's centred on a quiet man with literary pretensions

who lives with a beautiful and artistic foreign wife in a community that

looks up to him. Such are the similarities, I wonder if Jarmusch read

McGahern's novel.

Joe (Barry Ward) and Kate Ruttledge (Anna Bederke) met in

London, where the latter worked as an assistant to an art gallery owner.

They left the hustle and bustle of the English capital to begin a new

life in the west of Ireland, making a fist of running a small farm while

Kate remains in her role, making monthly trips to London. Joe has had

modest success with a previous novel and is in the process of trying to

fashion a followup. His inspiration comes from the people who wander in

and out of his life, who make up the film's supporting cast, all played

by aging men and women who possess the sort of beautifully craggy faces

we see on screen too rarely.

Like Paterson, Collins' film is largely composed of vignettes, most of which involve

some neighbour popping in for a chat with Joe and Kate, or Joe similarly

checking in with one of his elderly neighbours. There's Jamesie (Philip Dolan), a local farmer and the town gossip, who walks in a right shoulder,

left foot fashion which gives him the appearance of an inquisitive duck.

There's Patrick (Lalor Roddy, quickly becoming one of my

favourite character actors), a cantankerous old duffer who seems skilled

at everything from carpentry to laying out the dead. There's Bill (Brendan Conroy), an intellectually challenged man whose life was damned by the stigma

of being born out of wedlock in Catholic Ireland. There's Jamesie's

brother Johnny (Sean McGinley), who occasionally returns from

England, where he works a demeaning job cleaning toilets in a car

plant.

The interactions veer from kindness to cruelty, from withholding

emotions to spitting them out as though trying to quash a fire. Joe acts

as a neutral party observing the tos and fros of men who have known each

other for longer than he's been alive. He's like Patrick Kavanagh's poet

watching life pass him by on the Inniskeen Road, but unlike Kavanagh's

narrator, there's no bitterness here. Joe doesn't feel like he's missing

out on anything. In his eyes he has it all: a woman he loves, a home in

a picture postcard landscape and work that satisfies him.

The closest the film comes to introducing conflict is when Kate's uncle

(John Olohan) arrives from London with the news that he is

planning to retire from running the family gallery and that it can only

remain in operation if Kate returns to London. Kate is given until the

following May to make a decision, and as the narrative ticks off

Christmas and New Year's Eve we grow apprehensive that Joe's idyllic

life might come to an end. Being an Irish male and thus terrified of

conflict, Joe naturally avoids broaching the subject with his wife, but

it occupies his thoughts and finds his way into his book, which morphs

into an elegy for a life he expects to soon expire.

The film itself is an elegy to a disappearing Ireland, to a time when

ambition was for those who left, while those who remained found either

contentment or madness. It's a film about pausing to take it all in,

whether it be the way the slats of a half-constructed outhouse frame the

sky or the first spring warbles of a distinctive songbird. Collins

bookmarks his scenes with images of the Irish countryside that are so

beautiful you'd happily gaze at them for the remainder of the film. But

this film is all about its human characters, and how wonderfully human

they are. We fall in love with every one of them, even those who can't

love themselves. We listen to their bad jokes, their expressions of

hope, their confessions of regret. We watch as Joe and Kate glance at

one another during someone else's monologue, and we admire how easily

they can sit in the shared silence of a love that doesn't need verbal

validation. We're touched by all of it.

That They May Face the Rising Sun is on UK/ROI VOD now.