Review by Eric Hillis

Directed by: Darren Aronofsky

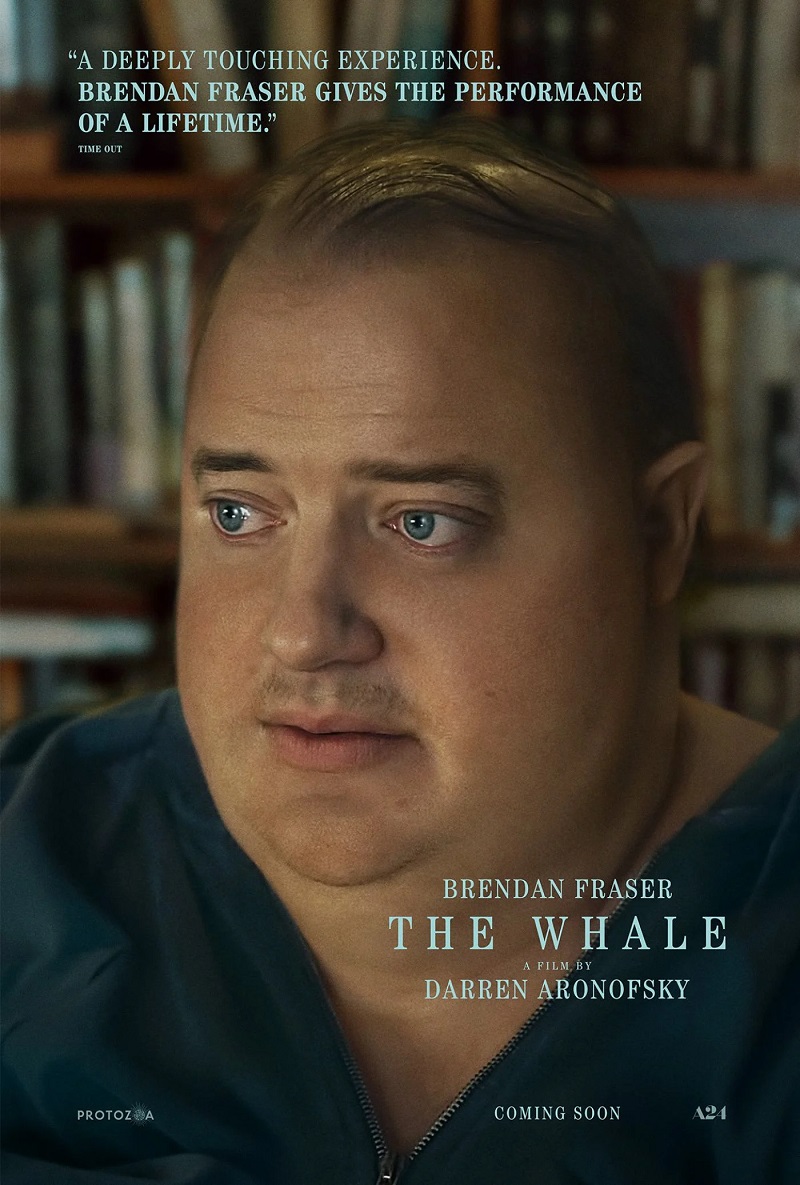

Starring: Brendan Fraser, Hong Chau, Sadie Sink, Samantha

Morton, Ty Simpkins

Most of us would have no qualms intervening if we felt someone we knew was

ruining their health with alcohol, drugs or cigarettes. In fact we're

encouraged by society to do so. Why is it then that we feel unable to do the

same for someone who is potentially killing themselves with their eating

habits? Of, course this only works one way. We're encouraged to speak up if

we see someone "wasting away," but if someone is piling on weight to the

point where it's affecting their health we're supposed to turn a blind eye

lest we be accused of "fat-shaming." Conversely, it's socially acceptable to

deride those who look after their bodies - you can use terms like "fitness

freak" and "health nut" and nobody will bat an eyelid. Both of my parents

lived shorter lives than they should have because they had terrible diets

and non-existent exercise regimes that ultimately clogged their arteries to

the point that meant they were unable to survive a heart attack and a bout

of COVID-19. I never mentioned their weight to them when they were alive,

because I was afraid of fat-shaming them, and also because I wasn't exactly

svelte myself (seeing my dad's grisly post-mortem results made me realise I

needed to change my lifestyle, though it took a long time for me to actually

do something about my weight). I'm not sure how we're supposed to have this

conversation, and it seems like a dialogue it's harder to have now than it

ever has been in the past. I'm not sure who is even allowed have this

conversation. If a fit person remarks on an overweight person's health it

will come off as "punching down," but for an overweight person to make the

same comments would seem hypocritical.

I don't know how to have this conversation, and based on

The Whale, neither do director Darren Aronofsky and writer

Samuel D. Hunter, the latter of whom is adapting his 2013 stage play.

I'm sure neither Aronofsky nor Hunter are cruel fat-phobes, and that they

come from a well-meaning place with this tale, but

The Whale never doesn't play like a case of punching down.

It's one of those patronising movies that makes you realise why

middle-Americans are so averse to what they call "coastal elites."

The Whale is set in the heart of what coastal American snobs

call "flyover country," in the MidWest state of Idaho, where Google tells me

31% of the population are obese. Our protagonist, English teacher Charlie

(Brendan Fraser), isn't merely carrying a few extra pounds - he's

morbidly obese, barely able to move his 600lb frame from his couch without

assistance. That assistance comes from home-help nurse Liz (Hong Chau), who has a personal connection to Charlie that allows him to feel

comfortable in her presence. While lecturing him to go to the hospital

before it's too late, Liz enables Charlie by bringing him multiple hot subs

and buckets of chicken every time she visits.

Charlie leaves the door unlocked for Liz, leading to an awkward moment when

Charlie's masturbation session (which almost leads to a heart attack) is

interrupted by the visit of Thomas (Ty Simpkins), a young Christian

missionary who decides he might be able to save Charlie's soul. Initially

it's unclear if Thomas feels this way because he disapproves of Charlie's

homosexuality or because it's clear Charlie doesn't have long left in this

world. Is Thomas on a selfish mission or one of genuine empathy? This is the

one ambiguous thread in a movie that otherwise hammers home every point as

though Aronofsky was irked by the general "I don't get it!" reaction to his

previous movie,

Mother!.

Not so nuanced is a subplot that sees Aronofsky rehash

The Wrestler, with Charlie attempting to reconnect with his estranged 17-year-old

daughter Ellie (Sadie Sink). Ellie refuses to forgive her father for

walking out on her and her mother (Samantha Morton) when he fell in

love with one of his students. Ellie is a one-note monster, described as

"evil" by her mother. We're inclined to agree considering the cruelty she

inflicts on both Charlie and Thomas, though we suspect she's simply hiding

behind her true feelings.

Set entirely in Charlie's apartment, The Whale has the

structure of a classic sitcom with various characters popping in and out to

make blunt points and occasionally deliver some backstory. We almost expect

an audience applause the fifth time Thomas awkwardly barges in. I'm

sympathetic with filmmakers who had to lower their ambitions due to pandemic

restrictions, but there's no excuse for a movie as uncinematic in its

storytelling as The Whale, which doesn't have a single memorable shot and is lit as though Charlie

lives in the apartment of a serial killer in some '90s David Fincher

knockoff. The entire story is told through dialogue, and this raises

specific problems. The trouble with using words rather than images, of

telling rather than showing, is that the audience is forced to take the

characters at their word. We have no option but to believe what we're told

here, so when Ellie tells us that her father's apartment stinks we have to

take the word of an unreliable source, as Aronofsky never uses visuals to

convey whether she might be correct or not. This is something that could be

communicated as simply as having a character open windows when they enter

Charlie's apartment, like how Grace Kelly turns on all the lights when she

enters Jimmy Stewart's gaff in

Rear Window, showing us that she's unaccustomed to the darkness he's become

comfortable living in.

But the lack of visual invention is the least of The Whale's problems. Its title is a reference to Moby Dick (what else?), with

Charlie so enamoured with a crudely written essay on Melville's book that

reciting its words can fend off his heart attacks (as alternative medicines

go, that really takes the biscuit). But if you want to have a conversation

about obesity, maybe a less mocking title could have been found. The movie

doesn't mean to deride Charlie, but at times he's shot in a manner that

recalls genuinely fat-phobic comedies like

Big Momma's House and the "Fat Bastard" character from

Austin Powers. Things aren't helped by cramming Fraser's frame into a fat suit. As fat

suits go it's one of the better ones I've seen, but it's always recognisable

as a fat suit and when Fraser is forced to shuffle around he looks like some

Japanese stuntman in a rubber Godzilla outfit.

Some have suggested Charlie should have been played by an actor who

physically matched the part, but that seems like something no insurance

company would touch with a barge pole. Casting an actual 600lb actor would expose how exploitative Aronofsky's

film really is, regardless of his intentions. Watching someone whose weight

means they could die at any moment play a character who knows he's in his

final days would be borderline snuff material.

Through the character of Ellie, there's a theme that sometimes you have to

be cruel to be kind (I admit I do like the idea that a surly teenage girl

makes for a great life coach because she'll have no qualms about pointing

out your every flaw), but it's an unconvincing one, as nobody is really able

to help Charlie except himself. In the end, The Whale seems to

victim-blame its unhealthy protagonist for the hurt his lifestyle has caused

others. If pizza left as bad a taste in the mouth as Aronofsky's film,

obesity might not be such a widespread problem.

Given the leaden script he's lumbered with, Fraser does a remarkable job

here. You can't help but warm to him, and his empathetic performance always

seems to be fighting against the film's otherwise guinea-pig-in-a-cage use

of Charlie as a test subject. When the camera gets in tight to Fraser's face

we can momentarily forget about the fat suit and focus on the actor as he

sells the pain of a man whose body is too wide to receive a hug. In her

limited time, Morton is equally impressive, and her one-word reaction to

Charlie's weight is one of the few moments of the movie that feels

genuine.

One of the cardinal rules of film criticism is that you shouldn't criticise

a film for not being the movie you'd like it to be. I can't do that with

The Whale, because I simply don't know what the good version of this movie looks

like. There's an important conversation that might have been started by

The Whale, but Aronofsky's condescending approach will likely shut down any

potential dialogue, which is a shame.