Review by Benjamin Poole

Directed by: Jeppe Ronde

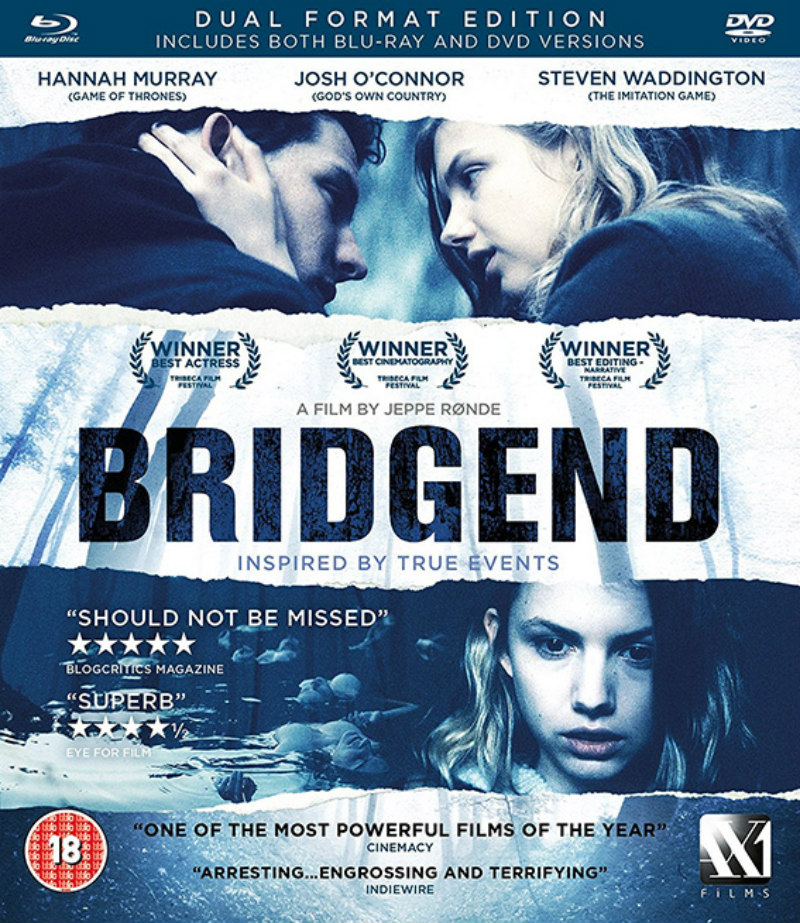

Starring: Hannah Murray, Josh O'Connor, Steven Waddington, Adrian Rawlins

A little while away from where I’m writing this, just a few miles down the valley, is the county of Bridgend. The county is built around the former market-town of Bridgend, and surrounding the town throughout the valleys are several small and remote villages which make up the rest of the green and pretty borough. Around 10 years ago, Bridgend county’s media profile was undesirably raised by a spate of teen suicides; a series of hangings which, between 2007 and 2009, totalled 26. The specific circumstances of the deaths were grimly intriguing, as the suicides were mainly young people in their late teens. The freak endemic nature of the deaths gave rise to desperate conspiracy: were these suicides part of a death cult? Could it be a Facebook thing? Was the media to blame? As is the tragic, illogical nature of such events, no one will ever really know, and therein lies the kicker. I just remember it was weird; weird and horrible: the proximity of the victims in location and age especially unnerving.

Jeppe Ronde, Torben Bech and Peter Asmussen’s Bridgend is an equally perplexing response to the sad events, a fictionalised narrative which takes the real-life suicides as a starting point into a family drama. Sara (Hannah Murray) and her copper dad Dave (Steven Waddington) move from Bristol to set up in the actual village of Pontycymer, where Dave has been reposted in order to investigate the suicides. Bridgend’s Wales is a misty, fecund arcadia; filmed entirely on location, cinematographer Magnus Nordenhof Jonck’s camera captures the soured fairy-tale look and feel of the Welsh valleys, a dark and imposing emotional landscape. Huge mountains (Llangeinwyr, Blaengarw) blot out the sky, and disused railway tracks, remainders of the long-gone coal industry, scar the landscape and lead to nowhere.

The way in which the central group of teens, whom Sara falls in with immediately, interact with this environment is central to the film. Autumn evenings are spent in the forest, with water, weed and White Lightening - the kids skinny dipping in the reservoir, playing chicken across the train tracks and chanting the names of their fallen comrades to the night. And, of course, it is the woods where they, following gnomic discussions on ‘internet chat rooms’, inevitably go to end it all. ‘We must ask ourselves why’, a vicar solemnly intones over the funeral of a lad which the film opens with, regretting the ‘vibrant young man’ with his ‘whole life ahead of him’. A life, Bridgend suggests, which was always subject to restriction: a character boasts that ‘we keep ourselves to ourselves around here’, and one of the film’s teens scoffs that a relative is a mineworker and a rugby player, ‘like everyone else, actually’.

Stereotype, much? Well, at one point, following Sara’s argument with someone or another (the film’s conflict is generally circumscribed to Sara having rows with her dad or one of the gang members), the Troubled Teen rushes out into the street and straight into the midst of a male voice choir (!), who are wandering the streets singing Calon Lan, as you do. I’m not proud to admit that this ill-judged bid for gravitas made me laugh out loud: it was simply ridiculous. As was the extremely insensitive teacher who, in the film’s pursuit of thematic weight, sets her highly vulnerable students Dylan Thomas’ And Death Shall Have No Dominion as a class exercise... There is a lamentable sense of hubris within Bridgend, at its ham-fisted attempts to tackle such a raw and emotive subject and make a cinematic sense of something so terribly beyond reason.

Indeed, if the film wasn’t spuriously built upon a foundation of actuality (the fact that over 20 children saw fit to kill themselves in this area), Bridgend would have little dramatic weight at all. The awful truth of the suicides is that there was no narrative logic to events, and therefore no ‘story’ to tell. Therefore, it is fitting that the film features mountains so significantly, as its pace is geological. Within the grim and gormless depictions of valley life we see the kids act like confused degenerates: they smash up the town in the name of ‘revenge’ for a dead girl, yet venerate other suicides on their silly little web page. Worse still, Bridgend offensively suggests that the local kids are something ‘other’, ignoble savages which horsey, middle-class Sara needs to be rescued from. There is no sense of trying to understand these teens or their extenuating circumstances; they are only ever seen in relation to outsider Sara. Similarly, Dad Dave’s dialogue consists mainly of phrases like ‘where have you been’ and ‘stay away from them’ (incidentally, Dave seems to be the only copper in the entire county). As the plot limps on, Sara begins a relationship with one of the lads and Bridgend becomes a tired Twilight with suicides, a familiar narrative that centres on Dave attempting to save his pony riding daughter from the savage horde that would tempt her towards death (like the mum in The Lost Boys, anxious over Michael falling in with David, say). Of course, it bears repeating that neither Dave or Sara actually existed IRL, yet the tens of kids who killed themselves, leaving their families bereft, actually did.

This bogus fetishisation of the Welsh working class queasily extends to Ophelia-esque images of the girls, floating naked in moonlit reservoirs, with their young breasts unnecessarily glowing in the silvery water. This sexualisation is continued by such scenes as the one where a kid graphically attempts to rape Sara, and a sex scene where another strangles her at the point of orgasm. It is rather confounding, this simplistic conflation of different types of violence. Perhaps the film wasn’t already grim enough, and such added nihilism was included because grim=serious=worthy, a dynamic which only the foolhardy adolescents of Bridgend, in all their righteous immaturity, would deign to accept.

Bridgend is on DVD/blu-ray August 7th from AX1 Films.