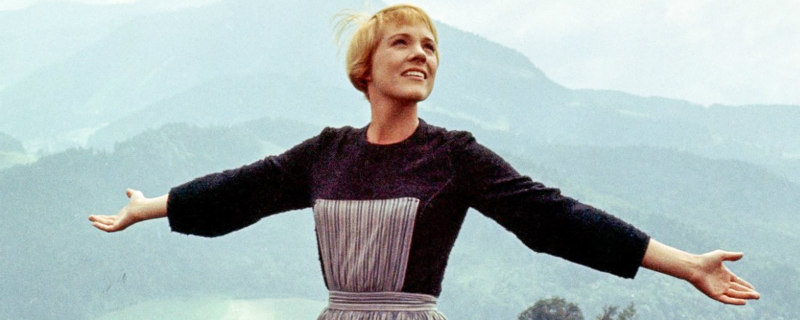

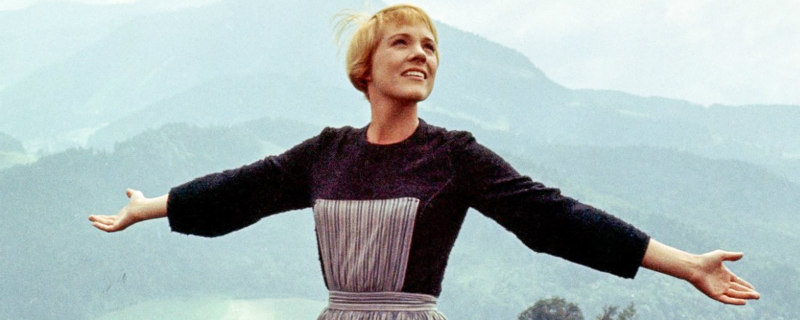

As The Sound of Music returns to UK cinemas, we look at how Robert Wise subtly shaped a classic.

Words by Eric Hillis

When we think of The Sound of Music, it’s usually Julie Andrews’ exuberant performance and the memorable songs of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II that first spring to mind. Indeed, those are the front and centre elements, and had lesser talents contributed to the film, it’s doubtful we would still be celebrating it five decades later.

Equally important though is the contribution of director Robert Wise, whose efforts were rewarded with a Best Director Oscar (he also received the Best Picture statuette). Wise wasn’t a flashy director, and never allowed his direction to overwhelm whatever story he was attempting to tell. Perhaps it’s for this reason that few studies have been written about Wise, but it’s exactly this subtlety that makes his work on The Sound of Music so interesting.

Upon release, the film received a harsh trouncing from a new generation of critics who saw it simply as empty Hollywood decadence at its worst. Now this seems like a case of failing to see the forest for the trees. Reviewing an earlier Wise film, 1954’s So Big, then Cahiers du Cinéma critic François Truffaut wrote that the film, “raises the classic, traditional Hollywood style to its highest degree of effectiveness.” This comment could be applied to Wise’s body of work as a whole, and particularly The Sound of Music, a movie as traditional as Hollywood ever produced, but one elevated to a work of cinematic art by its director.

Upon release, the film received a harsh trouncing from a new generation of critics who saw it simply as empty Hollywood decadence at its worst. Now this seems like a case of failing to see the forest for the trees. Reviewing an earlier Wise film, 1954’s So Big, then Cahiers du Cinéma critic François Truffaut wrote that the film, “raises the classic, traditional Hollywood style to its highest degree of effectiveness.” This comment could be applied to Wise’s body of work as a whole, and particularly The Sound of Music, a movie as traditional as Hollywood ever produced, but one elevated to a work of cinematic art by its director.

Let’s take a look at some examples of how Wise subtly employed cinematic techniques in his creation of a classic few critics would disparage today.

The opening:

The opening:

Wise had previously directed the 1961 musical masterpiece West Side Story. Both films are intimate dramas played out against a larger background, and both feature a common theme running through Wise’s work - the idea of the status quo being upset by the arrival of strangers. In West Side Story, it’s the encroachment of the Puerto Rican immigrant Sharks into the territory controlled by the native Jets. In The Day the Earth Stood Still, it’s the arrival of intelligent life from beyond the stars. In Run Silent, Run Deep, the appointment of Burt Lancaster’s First Officer kicks off a conflict with Clark Gable’s submarine commander. With The Sound of Music, this theme works twofold; we have both the arrival of the free-wheeling Maria at the disciplinarian Von Trapp house, and the arrival of the Nazis in Austria.

Wise opens The Sound of Music with a sequence that plays out like a reversal of his earlier musical’s opening. With West Side Story, Wise introduced us to his movie’s world with a montage of aerial shots, giving us a bird’s eye view of New York City. From such a perspective, the noisy, bustling city becomes serene, its usually overwhelming traffic noise reduced to a low distant rumble. Gradually, we zoom in on one small corner of the city, and with the clicking of a gang member’s fingers, we’re instantly dropped into a world of danger.

The Sound of Music opens with a similar sequence of aerial shots, this time over the Austrian Alps. At first, it’s an almost sinister scene, the imposing snow-capped mountains creating a sense of a hostile world. Gradually, however, the landscape turns green and we grow more comfortable with the stunning Alpine scenery. Just as Wise zoomed in on the tiny figures of the Jets, here he introduces us to his film’s protagonist, Andrews’ Maria, picking her out of the vast landscape as she frolics through the hills, singing her heart out. We’re instantly at ease in this world. As the film progresses, however, Wise will subtly create a sense of unease.

With West Side Story, Wise gradually humanises his characters over the course of the film. Conversely, with The Sound of Music, the threat of dehumanisation lingers and develops throughout.

Mise-en-scéne:

The term mise-en-scéne refers to the arrangement of actors, props, backdrops etc. in a shot. When done well, this can tell us more about a character than any monologue, and Wise was a master of mise-en-scéne. In The Sound of Music, none of the characters ever explicitly tell us how they’re feeling, yet we’re always aware, thanks to the director’s subtle positioning of both his actors and his camera.

Gates:

Gates:

The recurring motif of gates runs throughout The Sound of Music, and Wise uses them to tell us a lot about his characters’ place in the world of the story.

The first set of gates is seen as Maria leaves the convent, having been assigned to her new role as Governess of the Von Trapp home. Wise places his camera outside these gates, shooting Maria walking towards them from within the convent grounds. Framed behind these wrought-iron bars, it’s made visually clear that Maria’s outgoing personality has been imprisoned during her time at the convent. She walks through the gates into her new life, breaking into the musical number ‘Confidence’ on her way to the Von Trapp estate. Upon her arrival, we are greeted with yet another set of gates. This time, Wise’s camera is outside again, but so is Maria; it’s the Von Trapp house that is now viewed behind the bars. This suggests the Von Trapp home is a prison in its own right, something confirmed when we subsequently witness the authoritarian hold the Captain has over his children.

Maria’s arrival changes the dynamic of the Von Trapp home, turning it into a house full of song and play. During the musical number ‘Do-Re-Mi’, we return to the gates of the estate, but now they’ve been flung wide open, as Maria stands triumphantly between them during her vocal performance.

Later, however, when the Nazis have arrived in Austria and the Von Trapps attempt their late night escape, Wise places his camera on the outside of the same gates, now locked, once again imprisoning the Von Trapps in the grounds of their own estate.

During the wedding of Maria and the Captain, Wise again uses yet another set of gates inside the chapel, placing his camera so as to frame the nuns behind the gates after Maria emerges to tread the aisle. This is a beautiful way of illustrating Maria’s leaving behind her old life at the convent for her new one as Mrs Von Trapp. The sight of the nuns essentially self-imprisoned in this way is one of the film’s most powerful images.

In the suspenseful climax, as the Von Trapps hide out from the Nazis at the convent, Wise employs a final set of gates. With the Nazis, including Liesl’s previous beau, Rolfe, searching the grounds, the nuns hide the Von Trapps behind a set of locked gates. This time, Wise’s camera moves back and forth between both sides of these gates, visually imprisoning both the Von Trapps and the Nazis. The suggestion is that while the Von Trapps are temporarily imprisoned against their will, those who have succumbed to National Socialism have imprisoned themselves voluntarily.

The hallway:

The hallway:

The hallway of the Von Trapp becomes a key location, its expanse exploited by Wise and his carefully placed lens.

When Maria first arrives, she is left alone in the hallway. Wise shoots this in an extreme wide shot, dwarfing his subject against the backdrop of the empty hall. This conveys the sense that Maria is intimidated by her imposing surroundings, and may have bitten off more than she can chew by accepting the Governess position.

Later, the same hallway becomes the stage for another musical number, ‘So Long, Farewell.’ Now the hallway is filled with revelers, no longer imposing, and Maria is in complete command of her surroundings. This is short-lived, however, when Maria packs her bags to leave after her conversation with the Baroness. Once again, Maria is viewed in an extreme wide shot, alone in the vast hallway as she bids farewell to the house she had grown to call home.

The Edelweiss eyes:

The Edelweiss eyes:

‘Edelweiss’ may be one of the film’s quieter musical numbers, but it’s the one that tells us most about the relationship between the characters. Gathered in the Von Trapp living room are Maria, the Captain, his children and the Baroness. As the Captain sings, no dialogue is exchanged, but Wise has his cast speak volumes with their eyes. The Captain’s gaze is focussed on Maria, who reciprocates. The children’s eyes look longingly at both their father and Maria. Observing this dynamic, the Baroness looks to the ground, aware she is no match for Maria in the eyes of both her intended husband and his children. This is subtle cinematic storytelling at its finest, the mark of a great director.

These are some of the ways in which Wise applied his directorial skills to The Sound of Music. Without Wise at the helm, we’d likely still consider it a great musical, thanks to Andrews, Rodgers and Hammerstein, but Wise ensured it’s also remembered as a great movie.

The Sound of Music returns to UK cinemas in a new 4K restoration and on 70mm in select locations from Park Circus on May 18th.

The Sound of Music returns to UK cinemas in a new 4K restoration and on 70mm in select locations from Park Circus on May 18th.