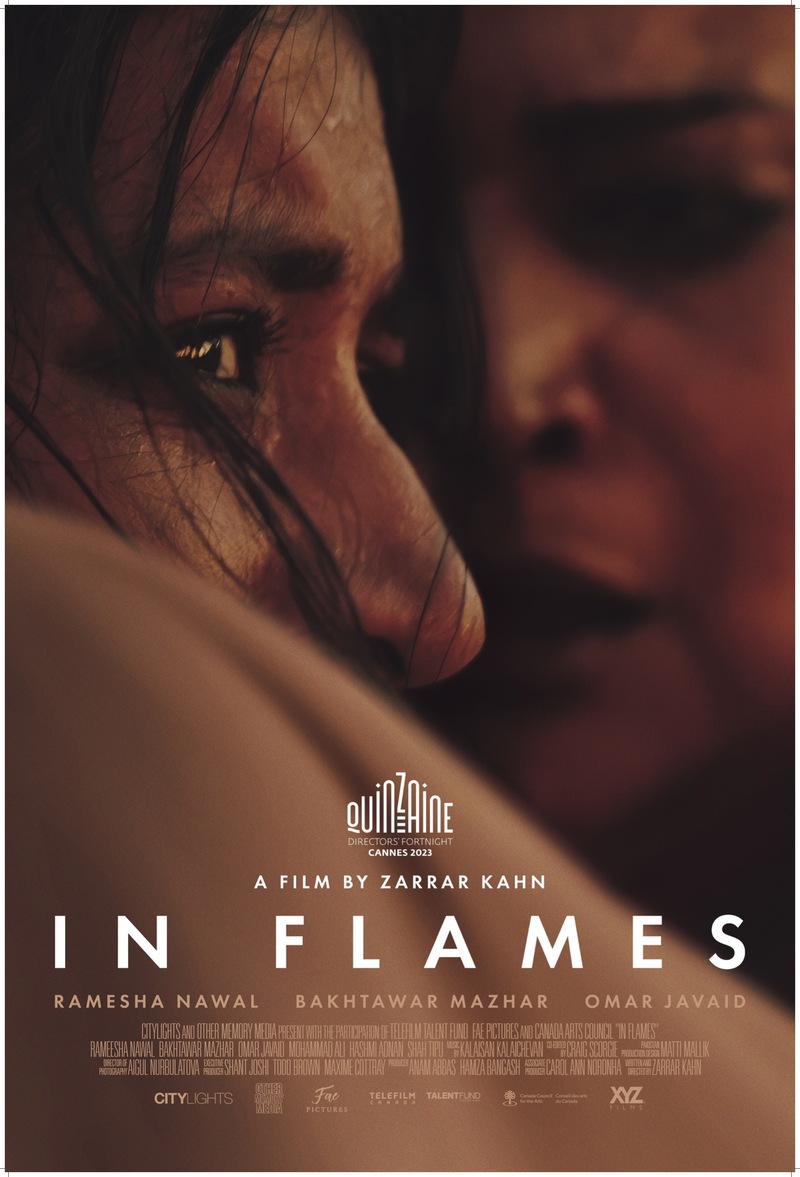

A mother and daughter are menaced by figures from their past following

the death of their family's patriarch.

Review by

Benjamin Poole

Directed by: Zarrar Kahn

Starring: Ramesha Nawal, Omar Javaid, Bakhtawar Mazhar, Adnan Shah Tipu

Over the last decade, Pakistan has accommodated a yearly series of

rallies called the Aurat which focus on the rights of women in the

country and make "demands for safety from endemic violence, accessible health care in a

nation where nearly half of women are malnourished, and the basic

economic justice of safe working environments and equal opportunities

for women." Not too much to ask, you'd assume, yet in 2014 a gender gap report

from the

World Economic Forum

ranked Pakistan 141 out of 142 countries, observing that women have less

power than men and are excluded from decision making positions, which

would delineate an urgent need for civic action. Post-Taliban, the

situation has degenerated further, with girls restricted from accessing

education, along with the abiding culture of honour killings. So, as it

always is, however bad the situation may be, it is that much worse for

young females (n.b., the age of consent in the country is irrelevant if

the couple

are married). It is only in the last three years that there has been an

Anti-Rape Act

in Pakistan.

Writing from a position of obscene ignorance, the above is a

condensation of my morning's research enacted to contextualise

Zarrar Kahn's stunning debut In Flames. A crucial film, because, as vital as research is, with its dry

aggregation of data and dates, information alone can be reassuringly

separate; an objective summary of something which is happening

elsewhere; so easy to compartmentalise. Narrative, which engages on an

emotional and subjective level, does not let us off the hook so easily. Following a pointed shot of a hand tied flag for the leftist Pakistan

People's Party (I think, at least... but the emblem certainly denotes

ideological purpose), In Flames opens at an Islamic

funeral, where mum Fariha (Bakhtawar Mazhar), late teen daughter

Mariam (Ramesha Nawaland) and little brother Bilal (Jibran Khan) mourn the death of their husband/father. Played in flashback by

Vajdaan Shah, the character is not given the status of a name:

perhaps because his position as patriarch is what prevailingly counts,

and such presupposed largesse means that he could be any man, really.

With the male head of the house gone, the family are left in a penumbra

of insecurity; financial and otherwise.

Kahn homes in on Mariam as she negotiates this new and uncertain phase,

which essentially entails avoiding the unwanted and invasive attentions

of the men and boys who have the run of the city. A thug smashes the

window of Mariam's car to grab at her, some big man attempts to shame

the girl for being outside ("Our women don't walk the streets") and then

later, having a platonic conversation with male companion Asad (Omar Javaid), an old man separates the two, maintaining that "this is not a

Bollywood film." The oppression is consolidated by the Catch 22 of

Fariha: Mariam is unable to inform her or the authorities of such

episodes, as this would result in the over-protective mother containing

her daughter even further. As bright yet beleaguered Mariam, Nawaland is

superb in an immensely likeable performance, and appreciation also goes

to costumer Zainab Masood, too, for Mariam's gorgeous array of

saris (the art direction often colour codes via clothes, with green

being a particularly resonant shade).

At this point, the horror, social as it may be, is manifest in

In Flames and produces a destabilising atmosphere of

threat and unpredictability. Further to this however, glimpsed in a

camera pan or at the corner of a frame, is the ghost of Mariam's father,

who seems to be haunting her, spookily presenting in her most private

moments: her bedroom, her (vivid, impressionistic) dreams, or when she

is visiting a spiritual healer. DoP Aigul Nurbulatova utilises

tight shots and frames action with shelving, windows and close walls,

engendering a restricted context. When the camera opens up to depict

panoramas of mountains, deserts and a sapphire ocean where fleets of

fishing boats bob as Asad takes Mariam on a trip, the effect is one of

oxygenated reprieve.

Unfortunately for Mariam and poor old Asad (a crucial aspect of

In Flames as he affirms that not every man is or needs to

be a tyrant), there is no escaping the curse. A reference point is

It Follows

(right down to the creepy beach house, in fact), as during

In Flames' (they also share initials - yikes!) running time the threat

substantiates in different personas: her father, a man masturbating

outside her window, and even Asad himself. However, whereas in 2014's

(!) film the terror was born of sexual anxiety, here the threat is

developed to be an imperious reification of the patriarchy itself, which

has been inaugurated by Mariam's sense of shame.

Another comparison could be Rosemary's Baby, which, like In Flames, is a film where ‘horror’ is just at the edge of the narrative,

imbuing the human drama with the emotive and archetypal propulsion of

genre storytelling (the Castavets there, Mariam's wrong-un uncle here:

common-or-garden human evil). The film shares Ira Levin's paranoia and

depiction of an assailable woman, and also uses this narrative to

propose a critical disequilibrium. It is heartening to see horror used

for what it should be in In Flames: a challenge to accepted norms and hegemony. Of course, you cannot

give a film a starred rating just because you agree with what it is

saying, so it is just as well that alongside its thoughtful and

important polemic, In Flames is a consistently surprising,

frightening and deeply entertaining horror film, too.

In Flames received its UK Premiere at Glasgow Film

Festival on 7 March.