Review by

Eric Hillis

Directed by: Bradley Cooper

Starring: Bradley Cooper, Carey Mulligan, Matt Bomer, Maya Hawke, Sarah Silverman, Michael Urie, Gideon Glick

Bradley Cooper takes inspiration from his own

A Star is Born

for Maestro, his biopic of the iconic composer/conductor Leonard Bernstein. As with

his directorial debut, Cooper's second film sweeps us up in a whirlwind

romance between two creative people only to leave us wallowing in the

inevitable misery of their incompatibility.

Bernstein (played by Cooper in remarkable make-up that some have described

as "Jewface") is introduced as a young firebrand sweeping (and sleeping) his

way through Broadway in the 1930s, when America was beginning to shake off

its cultural inferiority complex and loudly trumpet its homegrown composers

(while wrestling with the uncomfortable fact that they were almost

exclusively African-American or Jewish). Riding a wave of artistic success

and wrapping himself in a cloak of adoration, Bernstein meets the

Costa-Rican actress and socialite Felicia Montealegre (Carey Mulligan). Bonding over their shared passion for performing, the two fall head over

heels. Trouble is, Bernstein is gay, or at least bisexual, and Felicia must

learn to live with this inconvenience.

Cooper and screenwriter Josh Singer haven't structured their film in a way that asks for sympathy for Bernstein's

having to live a secret life, but rather for Felicia in having to put up

with it. Perhaps it's a sign of recent progress that the film doesn't feel

it needs to side with a gay man over a straight woman, but it does feel like

Bernstein is being viewed through a modern lens, one that can't see the

forest of 20th century homophobia for the trees of modern acceptance. It's

difficult to watch scenes of Bernstein hitting on young men without thinking

of the predatory likes of Kevin Spacey, so the viewer is forced to remind

themselves that Bernstein is behaving in this manner because society has

turned his sexuality into something sordid and sleazy. Verbally, Bernstein

argues his case, but it's always clear the film isn't really on his

side.

Felicia is portrayed as the sort of victim who might be considered one-note

were she not played by an actress as good as Carey Mulligan. The

English star is very good at playing women who present a strong front but

whose eyes betray a tortured uncertainty. Even if we can't fully condemn

Bernstein, we certainly sympathise with Felicia, who likely thought she

could "cure" his homosexuality, as so many women would have at the

time.

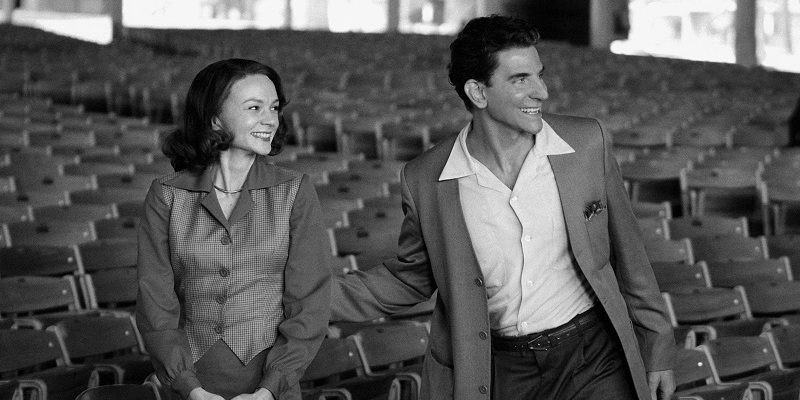

The early stage of the couple's romance and Bernstein's ascent is presented

in black and white, and Cooper schools Damien Chazelle in how to channel the

expressionism of classic American musicals. As Bernstein woos Felicia with

his musical talent, even inserting himself into the tight sailor outfit of

his Broadway hit On the Town, we tap our toes and click our fingers in time

with the beating of her swollen heart, and we're left in no doubt as to why

she would find this man so seductive.

Cooper switches to colour for the movie's second half as things fall apart

for Bernstein and Felicia. It's the colour of 1970s magazines, of

sweat-stained shag carpets and nicotine polished fingers. Much like Bob

Fosse's Lenny, Cooper's camera, which had previously been in Bernstein's youthful face,

views events at a remove, one of the film's highlights being a Thanksgiving

day row that positions Cooper and Mulligan at such extreme ends of the frame

it becomes increasingly uncomfortable the longer we contemplate the negative

space between the actors.

As a story of one performer who discovers they can't live in the shadow of

a fellow artist who burns too brightly, Maestro is a better

version of A Star is Born than Cooper's actual take on that

oft-told tale. As a biopic of a creative force it's somewhat lacking

however, and we learn practically nothing about Bernstein's relationship

with music. Cooper claims to have spent six years learning to conduct a

piece of music for a bravura six-minute sequence. Conversely, Jimmy Stewart

had mere weeks to prepare to play the protagonist

The Glenn Miller Story, yet Anthony Mann's film is one of the all-time great movies about what

it's like to be in love with music. Despite having made two movies about

music, I don't get the sense that Cooper has much interest in that

particular art form, but he sure knows how to get an audience swept up in a

doomed romance.